Mar 22, 2017

Strategies for Superbugs: Antibiotic Stewardship for Rural Hospitals

“Superbugs,” the trendy label for germs that can't be killed by modern medicine, are gaining traction. Tiny enough to escape notice and having no respect for geographic borders, they can hitch a human ride on anyone, ending up anywhere on the globe. Nevada was the location of the recent fatal case caused by one of those deadly bacteria. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the resistant bacteria taking this patient's life were probably acquired in India where the patient had previous medical care.

Here in the United States, similar bacteria are showing increased resistance to available antibiotics. Just several weeks ago, a new study reported these same germs are occurring more often in kids. Though these bacteria are still most common in adults, the researchers were concerned by “a trend toward increased risk of death” in their large study of children's hospitals.

These are the cases and statistics that trouble adult and pediatric infectious disease specialists, the doctors tasked with treating “superbugs.” These same cases and statistics trigger healthcare regulatory and accreditation agencies to introduce new clinical standards, like antibiotic stewardship (AS) programs specifically designed to help decrease resistance problems. Defined by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), AS programs are “a coordinated program that promotes the appropriate use of antimicrobials (including antibiotics), improves patient outcomes, reduces microbial resistance, and decreases the spread of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms.”

Last June, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a proposed rule, “Hospital and Critical Access Hospital Changes To Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care.” A major focus in this condition of participation is creating AS programs in all hospitals, regardless of size or geography.

AS Programs for Rural and Critical Access Hospitals: The Science of Implementation

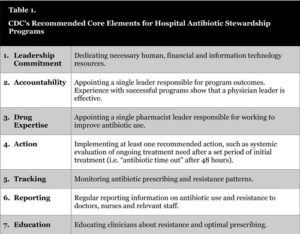

The CDC's hospital antibiotic stewardship toolkit lists the seven core elements of an AS program. (Table 1.) The journal Clinical Infectious Diseases reported that in 2014, almost 60% of the country's 4,187 hospitals had AS programs that didn't meet all seven core elements. Of hospitals with fewer than 50 beds, only one in four had all seven elements in place.

With bacterial resistance increasing, rural populations are as vulnerable as urban. Experts believe having a rural zip code shouldn't exclude any hospital from having AS programs. But how do small, rural and Critical Access Hospitals go about implementing an AS program? Teams in Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) across the country are working to figure this out.

Infectious disease specialist Dr. Eddie Stenehjem was brought to Utah's Intermountain Healthcare to help roll-out AS programs in the organization's 22 hospitals, including its 11 small hospitals and five Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs). After arriving, Stenehjem said he soon realized AS and infectious disease (ID) consultation wasn't happening for their smaller hospitals.

“It was very clear we weren't providing the services our smaller facilities needed,” he said. “So the next question was 'well, how do we do it?' We realized we had no idea. There was nothing in the literature on how to do stewardship in these smaller facilities. And when you look at national guidelines on stewardship, it's all based on large, academic medical centers for the most part. We realized we had the perfect opportunity to study this and move the science forward.”

With funding through Pfizer's Independent Grants for Learning and Change, Stenehjem and his colleagues completed the “first in-depth analysis of antibiotic use rates and selection patterns among small community hospitals in the United States.” Using a two-part approach, the first look was at antibiotic prescribing practices between Intermountain's large and small facilities.

“We found that antibiotic use in small hospitals is quite variable,” Stenehjem said, “but on average, it's similar to large academic medical centers or large community hospitals. And the spectrum of antibiotics used is similar, even though the smaller hospitals have less multidrug-resistant organisms.”

The second study, gaining special professional recognition, focused on Intermountain's 16 smaller hospitals. By evaluating pharmacy- and physician-based interventions specifically developed for the smaller hospitals' size, staffing, and infrastructure, the study, “Stewardship in Small Community Hospitals-Optimizing Outcomes and Resources” or “SCORE”, showed significant antibiotic prescribing reductions.

Stenehjem said his biggest surprise about the study was the type of patient hospitalized in his organization's small hospitals.

…small community hospitals see sick, complicated infectious diseases patients. With the complexity these providers manage, we need to provide help when they need it, because these patients want to stay in their community and not be sent to Salt Lake City.

“During our intervention study, I received over 1,000 phone calls requesting infectious diseases support,” he says, “and I realized small community hospitals see sick, complicated infectious diseases patients. With the complexity these providers manage, we need to provide help when they need it, because these patients want to stay in their community and not be sent to Salt Lake City.”

Now each of Intermountain's small hospitals receives tailored AS and ID consultation support through its new Infectious Disease Telehealth program.

“We're working with each hospital to set up individual stewardship programs that fit into their infrastructure,” says Stenehjem. “It's not all going to look the same. We're helping them develop their committees and the program members within their facilities.”

How Bacterial Resistance Develops

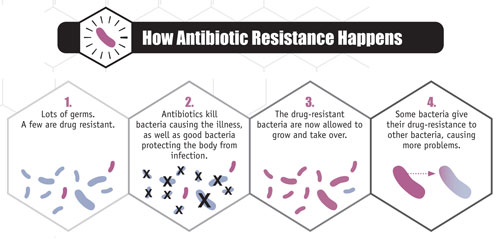

Using the example of a skin infection, first a large group of bad bacteria finds a place to settle in and take advantage, say a knife cut that occurred while fixing dinner. Next an antibiotic is prescribed. The antibiotic uses its machinery to kill off enough bacteria that the infection is no longer a problem. But sometimes, in that original group of bacteria, a few have special inner machinery of their own that resist the antibiotic's machinery. Being “resistant” to the original antibiotic, they live on, leading happy, reproductive lives. Often they even share their machinery with other bacteria (Figure 1). Now the few become many, and bacterial resistance becomes a big problem for all.

Stopping Resistance

The current science used by AS programs says “careful use” of antibiotics is the most important intervention in stopping resistance. Careful use starts with limiting antibiotics to bacterial infections and not using them for viral infections, a difference not always clear for front-line antibiotic prescribers. Patients also struggle with the difference between these infection types. But for an obvious bacterial infection, using the correct antibiotic in the correct dose at the correct interval for the correct time, bacterial resistance is less likely.

Creating AS Programs in Rural and Critical Access Hospitals

The Pew Charitable Trusts is also working with AS program development. In April, they reported on financial issues, staffing needs, and patient outcomes of 10 institutions with successful AS programs, none of which were rural. Yet in their August public comment letter to CMS regarding the proposed rule, Pew authors suggested that with any future compliance survey, CMS should “take into account the inherent resource limitations that exist for small hospitals and CAHs, where personnel with infectious diseases or stewardship expertise may not be readily available.”

Pediatric infectious disease physician Dr. David Hyun, co-author of the comment and a senior officer for Pew's Antibiotic Resistance Project, explained that after their April report, they also began looking at smaller, rural, and CAH facilities as part of ongoing AS work with the CDC. Hyun said that though he observed these facilities had a unique set of implementation barriers, he also saw they were equally matched with unique problem-solving skills for creating programs with limited resources.

What impressed me was these hospitals had tight-knit communities, and were organizations with an organic and natural problem-solving culture.

“What impressed me was these hospitals had tight-knit communities, and were organizations with an organic and natural problem-solving culture,” Hyun said, adding these facilities benefit from pooling resources.

Experts also note that smaller facilities benefit from cross-training among hospital departments. An example of a staff member with multiple roles is pharmacist Marc Meyer at Southwest Memorial Hospital, a 25-bed CAH located in Cortez, Colorado. In addition to his pharmacist duties, he helps run the hospital's employee health program out of the pharmacy, participates in the AS program and serves as the facility's infection preventionist, a professional who engages in multiple activities focused on protecting patients from healthcare-associated infections.

Meyer, a self-described “stewardship nerd,” has been interested in infection-related processes and procedures since 1999. His expertise has put him on teams involved with AS program implementation. Having worked on the National Quality Forum's guide for AS, he is also the only small hospital pharmacist on a panel for the Colorado Hospital Association's AS program, one of the largest programs of its kind in the nation, according to Meyer. He says a frequent question sent to him through this state program concerns AS program startups in small hospitals.

Right away I find out they are doing all these things they didn't realize were related to antibiotic stewardship that flows right into their stewardship project, and helps them make the core elements viable in their institutions.

“These small hospitals often tell me they just don't think they are doing anything,” Meyer said. “So I usually ask 'tell me what you are doing for infection control.' Right away I find out they are doing all these things they didn't realize were related to antibiotic stewardship that flows right into their stewardship project, and helps them make the core elements viable in their institutions.”

Bonner General Health's 25-bed CAH in Sandpoint, Idaho, had just that experience with their AS program start-up. Kathy Trosin, a Bonner registered nurse involved with both infection prevention activities and quality programs, said that in 2013 when she and other staff reviewed the CDC's core elements they realized “there was no way for us to go forward and we abandoned the idea.”

But in late October 2014, after watching a webinar sponsored by the Washington State Hospital Association, they changed their minds.

“The primary objective was to define a strategy and maximize resources, and that really spoke to us,” Trosin said.

Bonner got their AS team organized. In addition to Trosin, leadership consists of a physician champion from their emergency department, a pharmacist AS lead, and their lab manager. Additional strategic assistance comes from nursing, information technology, and quality and education members.

As Meyer predicts, the Bonner team discovered they had many AS core elements in place: audits, prescriber feedback, and antibiotic de-escalation plans, either stopping antibiotics or changing from an intravenous to an oral route.

Next they worked on provider accessibility to their hospital's antibiogram, a facility-specific guide showing bacterial resistance patterns and best antibiotic choices for infections. When they realized many of their daily AS activities were pharmacist-driven, they also enrolled all four of their pharmacists in an AS certification program.

“We feel we accomplished the majority of the CDC's core elements in the course of two years,” Trosin said.

AS Programs: Cost or Savings?

But what about costs? The CMS proposed rule states, “…the total annual cost for a CAH to establish and maintain an antibiotic stewardship program would be $44,800.” The rule also said that “although the overall magnitude of the paperwork, staffing, and related cost reductions to hospitals and CAHs under this rule is economically significant, these savings are likely to be a fraction of one percent of total hospital costs.”

The Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) Health Panel's public comments on the CMS proposed rule included comments on the economics of AS programs. Their letter said, “As a result of the anticipated additional training and technical assistance needed by CAHs, we believe that the estimated costs are under-represented.”

Jennifer Lundblad, President and CEO at Stratis Health, a nonprofit organization that specializes in healthcare quality, was a co-author on RUPRI's letter. Lundblad said calculating economic impact can be complicated since AS experts note start-up and maintenance costs must be balanced with expected savings from AS — savings associated with protecting communities from the expense and experience of antibiotic-induced problems.

We think about economic impact of costs, but there is also the economic impact of benefits.

“We think about economic impact of costs, but there is also the economic impact of benefits,” she said. “Often those are longer term and may not be as directly attributable, yet they are equally important because those health benefits are community benefits, with an economic benefit as an end result.”

Lundblad's comments lend to a closer look at AS programs from a cost-saving, disease-sparing angle. First, more judicious use of antibiotics should decrease side effects and lead to fewer costly emergency room (ER) visits. The CDC estimates one in five medication-related ER visits is due to an antibiotic, and almost 80 percent of those side effects are caused by allergic reactions.

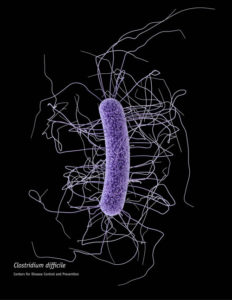

Second, more prudent antibiotic use should decrease rates of Clostridium difficile infections (CDIs). Referred to as “C. diff,” these bacteria live in the colon, normally kept in check by other bacteria. When antibiotics are given, the number of good bacteria keeping the balance become less, allowing C. diff to flourish. Severe diarrhea can result, triggering a cascade of related problems that are not just expensive to treat, but often are deadly. A 2015 CDC press release (no longer available online) noted CDIs result in “$4.8 billion each year in excess health care costs for acute care facilities alone,” and goes on to mention that “1 out of every 9 patients aged 65 or older with a healthcare-associated C. diff infection died within 30 days of diagnosis.”

Last Words on AS Programs: “Community” and “Patient Safety”

Meyer, the Southwest Memorial Hospital pharmacist, says AS programs have to be community programs where all antibiotic prescribers in and outside hospital walls work together. Meyer said the main focus of this collaboration is an AS goal that shouldn't be forgotten: decreasing bacterial resistance.

“To me, stewardship means community. It means clinics, ambulatory surgical centers, nursing homes, dentists and veterinarians, anyone prescribing antibiotics, cutting down on antibiotic days when appropriate,” he said.

Sarah Brinkman, a program manager who works with Lundblad at Stratis Health, said the timing of AS proposals and regulations can also be viewed as a community opportunity.

“The new proposed rule for antibiotic stewardship in hospitals came out around the same time that the final rule requiring nursing home antibiotic stewardship came out,” she said. “This was just a month before the new CDC guidelines for outpatient antibiotic stewardship came out. So it's really a perfect opportunity for communities to work together and identify the best approach for their patient population.”

Brinkman also explained how community collaboration like this benefits patients.

“Patients don't experience care in the same way we organize care,” Brinkman said. “They just experience their healthcare, and they should have the same experience regardless as an inpatient, or in the clinic, in the emergency department, or in the nursing home.”

With regards to resistance and the pressure it puts on the effectiveness of the current supply of antibiotics, Meyer worries what will happen if communities don't work on this together.

“We know what a post-antibiotic era looks like. All we have to do is look back before 1927 when people died of simple skin infections and pneumonia when we had no antibiotics. It was common then. Now, that's seldom heard,” he said.

Bacterial resistance has no respect for age, affecting the young along with the elderly. It has no respect for geography, making its presence known in both urban and rural areas. And when new regulations targeting bacterial resistance issues begin, Pew's Hyun said it's easy to lose sight of the prime focus of AS programs: patient safety.

Antibiotic stewardship is a patient safety issue. It's a patient safety issue that's global, that's regional, and it's a patient safety issue that's local.

“Antibiotic stewardship is a patient safety issue,” Hyun said. “It's a patient safety issue that's global, that's regional, and it's a patient safety issue that's local.”