May 01, 2019

Reducing Cancer Among Native Populations: Models for Research, Prevention, and Treatment

by Jenn Lukens

Cancer. The “C word” can immediately induce fear of what's to come and many questions about next steps. The diagnosis has become all too common for American Indian and Alaska Native populations (AI/AN), for whom cancer is the leading cause of death for women and the second leading cause of death for men.

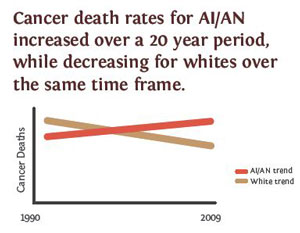

A 2014 American Journal of Public Health article showed that, while the cancer mortality rate decreased for White populations in the United States from 1990 to 2009, the rate rose steadily for AI/AN populations during that time. The article was considered groundbreaking because the study methods were aimed at reducing the racial and cause of death misclassifications of Native people that are commonly seen in mortality data. It ultimately provided a more accurate picture of cancer mortality for the AI/AN population.

Root causes of AI/AN cancer incidence and mortality rates are still being evaluated. Along with genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, cultural influences, diet, and substance use, the lack of access to medical information and services has also contributed to the high AI/AN cancer mortality rates. However, researchers, nonprofits, tribal healthcare facilities, and cancer centers are stepping up to address these factors and create solutions. Across the nation, models for cancer research dissemination, prevention, and treatment are emerging to engage Native populations in cancer care.

Cancer Research: Including Community Participation

Dr. Rodney Haring, PhD, MSW, is an enrolled member of the Seneca Nation of Indians and an assistant professor of oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York, one of 49 Comprehensive Cancer Centers in the United States. During his time at Roswell, he learned that nearly 300 AI/AN samples representing many tribes had been collected in the past decade for cancer research and stored within Roswell Park's bio-repositories. Since Roswell is not located on tribal land, specimens donated at the center were not technically under tribal oversite. But Haring thought it important to consult tribal leaders on what to do with the donations, including ethics of storage, research, and use of the samples. “Even though individuals can do this on their own accord, the communities need to be involved in that process. Tribal government needs to have a voice,” explained Haring.

Since Haring's work at Roswell includes connecting American Indian and rural communities to patient care and research services, he led the process of proposing community-based participatory research (CBPR) for tribal communities regarding these cancer specimens. The model engages each cancer specimen donor from both regional tribal communities and Native urban populations in decision-making, asking questions like “What policy, research guidelines, safeguards, or protections should be included in biospecimen cancer research?” and “What does biospecimen research or genetic research mean for our future generations?”

Because of its nature, there is often a stigma associated with Roswell Park Cancer Center in the minds of many Native people, according to Michael Martin, director of Native American Community Services of Erie & Niagara Counties, Inc. “Unfortunately, a lot of people think, 'That's just where you go to die,' and so they resist treatment or even going to the hospital,” he said. That mindset, coupled with a general distrust in medical institutions based on past experiences, can turn many Native people away from seeking cancer care.

Martin has worked closely with Haring on multiple efforts. The two have applied for grants that would build cancer awareness in Native communities and have conducted focus groups to help develop culturally competent ways to approach Native populations for information sharing. This method of research stems from Haring's social work background.

He literally and figuratively meets them where they are at, an important step in building trust with a Native community.

“He literally and figuratively meets them where they are at, an important step in building trust with a Native community,” Martin said of Haring.

Haring often says to those who are curious about his work, “My laboratory is out in the community. So if you want to meet me, come out to the local diner and we'll have lunch.” He encourages scientists and medical professionals to apply similar approaches to get a better pulse on the people they serve.

Haring explains why his community-based participatory research approach uses interdisciplinary sciences and medicine in this video:

According to Haring, disseminating cancer research to Native populations is essential for reducing cancer rates, but the method of doing so is the key to reaching AI/AN populations. “The common way to share results are manuscripts, meaning a paper that's published. But they usually sit in a journal somewhere on someone's bookshelf or in an electronic warehouse. Many of the papers are written in Western science contexts and do not always translate to Indigenous sciences or tribal community usefulness.”

Tips for Medical Researchers

Dr. Rodney Haring's suggestions for presenting cancer research to American Indian populations:

- Explain how the research benefits the community

- Get approval before starting the research process

- Discuss intellectual property rights (for example, genetics and biospecimens)

- Include key points on summary sheets

- Offer resources written in tribal languages

- Replace medical terms with lay terms

- Hire people from within the community

- Consider gender structures within communities

- Honor Indigenous sovereignty

- Include the community-based participatory research (CBPR) process

RHIhub's Topic Guide Conducting Rural Health Research, Needs Assessment, and Program Evaluation has more information about community-based participatory research.

Haring identified the American Indian

Cancer Foundation (AICAF) as one organization that is

getting research “off the shelf and into the

hands of the people.” Although the Foundation

is based in Minnesota, Haring has seen AICAF literature

displayed at his local health center on Seneca Nation's

Cattaraugus Indian Reservation. “That tells me

that nationally they are doing a good job providing

Native-sensitive data and screening materials.”

Cancer Prevention: Early Detection and Vaccination

Kristine Rhodes, MPH, is a member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and has been the director of AICAF since it formed. She has helped the organization grow from being solely focused on colorectal cancer in the Northern Plains region to bringing national awareness and prevention for all cancers affecting AI/AN populations.

It's not necessarily that we are getting more cancer than other populations, but other populations have access to the advancements that have been made in cancer, and those are really around better screening options.

In the 20th century, the number of deaths from cancer in Native populations were reportedly much lower than other populations. Rhodes attributes the recent uptick in mortality rates to late-stage diagnoses: “It's not necessarily that we are getting more cancer than other populations, but other populations have access to the advancements that have been made in cancer, and those are really around better screening options.” Because of that, AICAF has chosen to focus on “low-hanging fruit” by promoting early cancer detection.

For example, lung cancer accounts for more deaths in Native populations than colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer combined. In 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force identified annual screening for lung cancer in adults with a smoking history as an acceptable strategy to reduce lung cancer mortality rates. The concern, Rhodes pointed out, is that these types of screenings are more commonly used in large, urban healthcare centers than in Indian Health Service and Tribal Health Programs. By bringing multiple partners to the table, getting resources for screenings in tribal clinics, like low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for lung cancer, has become a goal of AICAF.

Along with the push for more screening methods is AICAF's promotion of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. According to Rhodes, this vaccine is a big win for AI/AN communities on several levels. First, the vaccine can address the high rate of cervical cancer in Native women (Rhodes herself was diagnosed with cervical cancer in her early twenties, an experience that inspires her work with AICAF). Second, the HPV vaccine can also prevent not only cervical, but also penile, vaginal/vulvar, and throat cancer. Third, the fact that American Indians vaccinate their children and adolescents at much higher rates than they vaccinate themselves provides an opportunity. As is a part of the general philosophy of many Native cultures: “We often take care of everybody else before we take care of ourselves,” explained Rhodes.

Cancer Information Dissemination: Sharing Resources and Model Frameworks

Making information available in a culturally appropriate way to those who have donated their own specimens to science is a concern for advocates like Haring and Rhodes. For example, when Haring presented his findings on cancer mortality rates from a study (see findings reported in the Journal of Cancer Education and Cancer Health Disparities) conducted with his colleagues, the feedback received from Haudenosaunee tribal leaders was that the focus on disparities was too morbid. “We said, 'You are right.' One thing that we will include in the next round of research is to look at survivorship data and show the resiliency of people. It's good to present both sides. We need to provide that balance when presenting our research,” explained Haring.

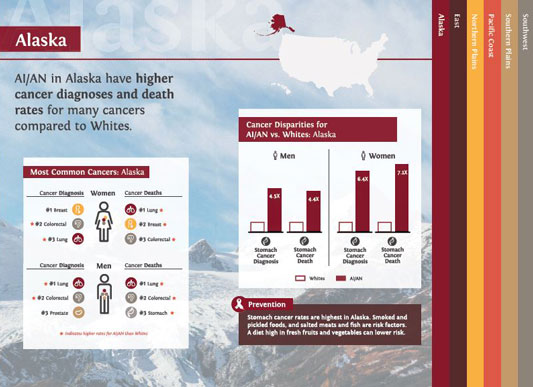

AICAF is disseminating information to Native populations by providing data in a user-friendly manner. The Foundation took the 2014 study Disparities in Cancer Mortality and Incidence Among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States and created infographics that outline common cancers, gender disparities, and mortality rates in each region.

The important work of taking the regional data down to the tribal level is critical. We really need to know what's happening in our communities, to know if we are making a difference and when we need to change our gears.

Since there is a lack of information specific to Native populations, the infographics have become popular resources for Native healthcare systems and advocacy groups. “The important work of taking the regional data down to the tribal level is critical. We really need to know what's happening in our communities, to know if we are making a difference and when we need to change our gears,” said Rhodes.

AICAF offers around 30 resources, including brochures, posters, and banners, available to download or order at no cost. All resources are culturally tailored and can be written in a tribe's native language.

AICAF has also partnered with healthcare systems to develop and share model frameworks. Online resources for providers give direction for treating tobacco addiction. Screening tools help providers decide next steps with patients, and webinars on cancer-based topics will soon qualify for Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits.

AICAF has tried to find the best avenues to reach the broadest audience in the shortest amount of time. Its outreach campaigns have utilized multiple avenues of dissemination like social media, conference presentations, and community events.

One of AICAF's most successful campaigns is Indigenous Pink Day. Celebrated every third Thursday in October, it calls attention to breast cancer in Native women. “Although it's not the most common cancer, breast cancer is the most popular, no matter what community you are in. It must be the women behind it and the people who love the women,” Rhodes said. Each site receives a box of resources and tools to run a campaign through their local clinic and on social media. This year, 23 tribal clinics participated, the Phoenix Indian Medical Center (PIMC) in Arizona being one of them.

Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Approach

The Phoenix Indian Medical Center has several factors that make its Cancer Care Program appealing to Native people who come not only from tribal regions across Arizona, but from all over the nation. One is their unique partnership with the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Phoenix, Arizona. The contract between the two centers has existed since 2006, bringing oncology specialists and state-of-the-art cancer care to PIMC patients. “They chose to come here versus us trying to get all patients to Mayo. That's a difference between us and a lot of other cancer centers,” said Nurse Practitioner Timothy Mathews, who leads the PIMC Cancer Care Program.

Our healthcare systems are extremely complex and overwhelming; we have patients who are coming from rural areas, and these complex healthcare systems make it challenging to 'connect the dots' to ensure our customers receive optimal and timely care. Our goal is to guide the patients through their cancer journey.

The program's “Pathways Process” is a comprehensive approach to cancer that includes care coordination, spiritual care, behavioral health services, insurance enrollment, and access to primary care and specialists for co-occurring conditions. “Our healthcare systems are extremely complex and overwhelming; we have patients who are coming from rural areas, and these complex healthcare systems make it challenging to 'connect the dots' to ensure our customers receive optimal and timely care. Our goal is to guide the patients through their cancer journey,” said Mathews.

Mayo oncologists provide consultations, hematology services, and diagnoses with help from a mobile biopsy unit. The fact that oncologists come from Mayo's comprehensive cancer center to see patients at PIMC helps break down barriers like transportation that may have previously existed. Patients who might qualify for participation in clinical trials or who need inpatient chemotherapy or specialized surgical procedures are often referred to the Mayo Clinic's Arizona campus. Before meeting with the specialist, PIMC takes care of the “staging” of each patient, including pathology preparation and bone, PET, or CT scans. PIMC's relationship with Mayo Clinic helps accelerate the process of care for patients with aggressive or rare cancers as pathology samples can be sent immediately to Mayo Clinic and the results made quickly available.

Mathews attributes PIMC's high survival rate for patients diagnosed with aggressive cancers to the Pathways Process and the Mayo partnership: “As an NP that is seeing a plethora of different cancers, I cannot be an expert on any one type of cancer as there is too much scientific information to stay current. However, with the Mayo oncology team, we will talk to their oncology breast cancer expert, or a lymphoma expert, or the sarcoma expert because that's their bread and butter. Since they are focused on one type of cancer, the Mayo oncologists are up-to-date on the latest research.”

PIMC's challenge to treating cancer patients is being aware of additional barriers that stand in the way of a patient fulfilling their Pathways Process. This requires providers to ask for more details like “Do you have running water?” and “Do you have a cell phone?” Because PIMC is an Indian Health Service facility, patients get access to social services that can offer the patient needed resources on the spot.

PIMC's way of cancer care can be applied to other tribal healthcare facilities but, Mathews acknowledges, may not be a universal solution: “Each place you go has unique pathways that need to be adapted to each patient, depending on their diagnosis, where they live, and financial resources.” He explains more in this video about how the PIMC and Mayo partnership helped Elena Blevins beat cancer: