Sep 09, 2020

Contact Tracing: Training New Workers and Connecting with Rural Residents

by Allee Mead

The Whiteriver Indian Hospital in eastern Arizona saw its first COVID-19 case on April 1. Physician epidemiologist Ryan Close, MD, MPH, said that the hospital's service area, about 18,000 American Indian people on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation, “had some of the highest case counts per day as anywhere seen in the country.” Contact tracing was an important step to help bring these numbers down.

In addition to treating COVID-19 patients, Close said that the hospital's role was to make sure residents could access testing and to proactively test those in close contact with individuals with COVID-19. The hospital's contact tracing initiative starts with a phone call, in which the contact tracer explains that the person receiving the call has tested positive for COVID-19 and asks to meet in person to discuss contact history.

Every day, a team of contact tracers wearing personal protective equipment visits high-risk individuals and assesses their symptoms. “High-risk” outreach is focused on those who have tested positive for COVID-19 and are at particular risk for poor outcomes and deterioration. This daily effort requires its own team of about four to six people, who meet with the larger contact tracing team twice a day.

Besides checking symptoms, Whiteriver Indian Hospital conducts in-person contact tracing because its service area has poor cell phone reception and not everyone has landlines. This was not news to the hospital's public health nurses, who were already conducting in-person contact tracing for other communicable diseases. Their expertise led to the hospital's COVID-19 contact tracing strategy. Close added that the hospital had to “quickly double and triple [its] contact tracing capacity to be able to send people into the field.”

Across the country, contact tracing continues to be an important step in combatting the coronavirus pandemic, especially as schools and businesses open up and as community members become more active outside the home.

In addition, ethnic minority populations have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. For example, 1.3% of COVID-19 cases (in which race and ethnicity were known) reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, even though they make up 0.7% of the United States population. The cumulative incidence (or cumulative cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 population) among AI/AN people was 3.5 times the incidence among white people.

In-Person Contact Tracing

Whiteriver Indian Hospital's contact tracing teams travel with pulse oximeters to test all household members' oxygen saturation, regardless of whether a person feels sick. Close has reported cases in which people have not felt sick but had low oxygen levels: “At the peak of the epidemic for us, in one in five households that we would trace, we would find someone who unexpectedly had low oxygen and had to be hospitalized.” Now, he said, that happens one in 20 households.

In addition, a contact tracing team offers to test everyone in the household for COVID-19. The Whiteriver Indian Hospital has point of care testing on site, so the team can collect a test sample, bring it back to the facility, and have a result in 15 minutes.

If the test result is positive, the team returns to that home to do additional contact tracing and determine who outside the home should be contacted (for example, coworkers or a child's other set of grandparents).

Close said the onsite testing “collapses a process that in many public health facilities is divided among institutions.” At Whiteriver Indian Hospital, the process “all gets collapsed into one person, which probably cuts down multiple days.”

Contact tracers at Whiteriver Indian Hospital include public health nurses, outpatient nurses, health technicians, medical assistants, physical therapists, physician assistants, pharmacists, doctors, and community volunteers. Contact tracers travel in teams of two when going on home visits. Teams are paired up based on how their strengths complement each other: for example, pairing someone's medical expertise with another person's language skills.

What good is that professional and their 20 years of education if they can't get from the hospital to the person's home? A community volunteer will know the language, the people, the community, and the roads. You can't buy that [expertise] and you can't train it into people.

Emphasizing the paired importance of medical expertise and cultural competency, Close said, “What good is that professional and their 20 years of education if they can't get from the hospital to the person's home? A community volunteer will know the language, the people, the community, and the roads.” He added, “You can't buy that [expertise] and you can't train it into people.”

Of course, these skills are not mutually exclusive: Close recruited a number of health techs and nurses from the community, with medical expertise as well as cultural competency, to the contact tracing team. “As a white male of privilege and a physician,” Close said, “I'm trying to be aware of how little I know about the people I serve so that I can serve them better, by surrounding myself with people who can inform me on what I need to know to lead the team.”

Developing Training for Contact Tracers

Up north, the Alaska Center for Rural Health and Health Workforce (ACRH-HW) is leading efforts to train enough contact tracers to meet demand. ACRH-HW is housed in the state's Area Health Education Center (AHEC) program, which is funded through the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). Part of the AHEC program's work is continuing education and training, so it was a natural fit for the ACRH-HW to “rise to the occasion,” ACRH-HW director Gloria Burnett said.

Alaska did not have many COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the pandemic, Burnett said, so that gave the state time to prepare. In May, the Alaska Division of Public Health projected that the state would need 500 additional contact tracers to address the pandemic. The division was looking for someone to create a training procedure and a way to hire contact tracers in a temporary capacity. In addition, the state needed experts in using the new documentation software that contact tracers would use.

Burnett said the ACRH-HW already had established relationships with many community health centers and Critical Access Hospitals across the state and could figure out training logistics, registration, and other non-curriculum aspects. The Division of Population Health Sciences, housed at the University of Alaska Anchorage, had the content matter experts to develop the training curriculum.

The training is asynchronous, so trainees can work at their own pace on their own schedules. If a trainee is inactive for a specified amount of time, they receive an email explaining that their account will be deactivated unless progress is made by a certain deadline. Removing inactive trainees from the program allows people on the waitlist to fill those vacancies.

In Washington, the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice was tasked with creating a contact tracing training for a national public health audience. The Northwest Center is housed at the University of Washington School of Public Health and serves Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska.

To develop this training, the Northwest Center received funding from the Kansas Health Foundation and contributions from the Kansas Health Institute and the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, because their state needed a training like this for its workforce. The Northwest Center assembled a team of instructional designers, e-learning experts, and subject matter experts.

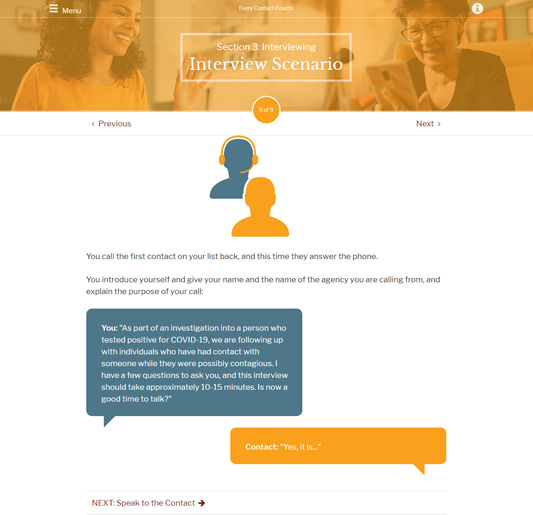

University of Washington professor of epidemiology Dr. Janet Baseman reported that since the Northwest Center already develops online training, it had the infrastructure in place to create a training for contact tracing. That existing infrastructure allowed the center to create Every Contact Counts quickly — in fact, they created the training in under three weeks. Since Washington was one of the first states hit with COVID-19, the Northwest Center was able to bring real-life examples into the training.

Free for public health audiences, Every Contact Counts takes 60 to 90 minutes to complete. Trainees learn how to describe contact tracing to the people they're calling and how to complete interviews. Trainees also watch skill-building videos and complete quizzes and exercises.

Customizing Training Curricula

Because many organizations don't have the time or resources to create a training curriculum, the Public Health Foundation (PHF) has also stepped in to bridge those gaps by taking existing curricula and creating a customized training package at the request of health departments.

PHF, celebrating its 50th year, is a

national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that

develops tools, trainings, and other resources concerning

quality improvement, performance management, and

workforce development. For the last eight years, the

foundation has provided onsite and remote assistance to

about 500 health departments. In addition, its TRAIN Learning

Network has 2.5 million registered learners, 280,000

of whom are governmental public health professionals.

PHF, celebrating its 50th year, is a

national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that

develops tools, trainings, and other resources concerning

quality improvement, performance management, and

workforce development. For the last eight years, the

foundation has provided onsite and remote assistance to

about 500 health departments. In addition, its TRAIN Learning

Network has 2.5 million registered learners, 280,000

of whom are governmental public health professionals.

PHF president and CEO Ron Bialek said that when the pandemic emerged, he saw an increasing amount of COVID-related training, including for contact tracing. PHF first developed a set of tailored live searches on different training topics available through the TRAIN Learning Network, to make it easier for people (health departments as well as voluntary organizations and companies) to find the training they're looking for. Between March 1 and August 1, PHF received about 125,000 visits to that set of live searches and over 100,000 trainings taken as a result.

We were hearing from health departments of practically all sizes and shapes, rural, urban, suburban, that they're overloaded. They were having difficulty with figuring out how to effectively train people and, especially in rural areas, they didn't necessarily have the time, the equipment, the expertise to develop the training themselves.

In addition, Bialek and his team wanted to ease the process of contact tracing for health departments. “We were hearing from health departments of practically all sizes and shapes, rural, urban, suburban, that they're overloaded,” Bialek said. “They were having difficulty with figuring out how to effectively train people and, especially in rural areas, they didn't necessarily have the time, the equipment, the expertise to develop the training themselves.” Along with developing a training, health departments would need to provide contact tracing forms, consider local privacy rules, and figure out how to keep track of who has completed training.

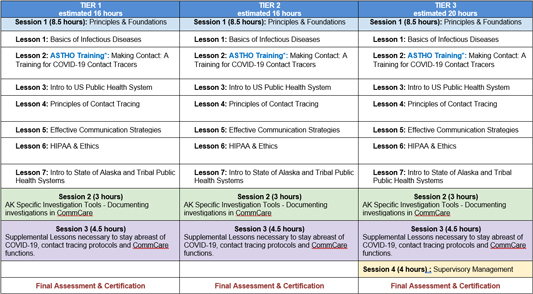

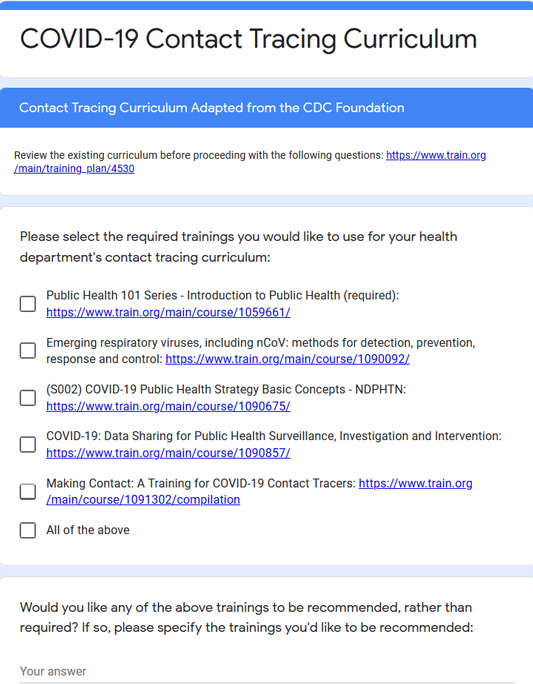

To address these issues, PHF launched a free service in July that customizes contact tracing training curricula for state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments. Health departments can choose nationally available training, state-offered training, and any forms like privacy policies, and PHF combines them into one online curriculum package, which can be launched and tracked through the TRAIN Learning Network.

To date, PHF has received curriculum customization requests from rural and tribal health departments in nine states: Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Idaho, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

PHF has received about 80 requests total from health departments of any size. In some cases, Bialek said, “It turns out the health department doesn't really want a customized curriculum, but they never knew where they could even find the training.” So PHF connected them with a training package that already existed instead of customizing one for them. “At the end of the day,” Bialek said, “we don't want to insist you have to use [a customized curriculum] package. We want to help you find what you need.”

At the beginning of this project, program coordinators thought the easiest approach for this service was to have health departments contact one person, either through a call or an email, and explain what they wanted in their curriculum package. Investigating why that approach resulted in so few requests, the coordinators found that even a 20-minute phone call was more time than these health departments could give.

“So we then put our heads together and said, 'How can we make this even easier?'” Bialek said. His team decided to create an online form in which health departments could choose between building their own curriculum or starting with the CDC Foundation adapted trainings.

If health departments want to add any local resources, they send a hyperlink or an electronic file of the material to PHF. In less than a week, PHF sends the curriculum package to the health department. Each package comes with an access code to help health departments limit access to and keep track of who's accessing the training. Health departments also receive an orientation about tracking.

Just by switching to the online form, Bialek said, requests increased from around 10 requests in the first couple weeks to its current tally of about 80.

Statewide Successes

In Alaska, as of July 21, over 1,300 individuals had expressed interest in becoming contact tracers; of these, 228 people had completed the ACRH-HW training process. Burnett also pointed out that the first 500 people to complete training receive a stipend, funded through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and matching funds from the state of Alaska.

The ACRH-HW also partnered with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium to recruit licensed professionals. In addition, the ACRH-HW markets the training opportunity throughout state nursing home and hospital associations and tribal health systems.

We really wanted to make sure that even the spots throughout the state that might only have one public health nurse serving had a supplemental workforce to assist them with those contact tracing efforts.

Burnett's organization made sure every region of Alaska was represented when recruiting people to take the contact tracing training. “We really wanted to make sure that even the spots throughout the state that might only have one public health nurse serving had a supplemental workforce to assist them with those contact tracing efforts,” Burnett said.

In Washington, Northwest Center director Dr. Betty Bekemeier said that within days of Every Contact Counts being launched, over 1,000 people had taken the training. In Kansas, the Department of Health and Environment requires this training for all new contact tracers. Bekemeier added that a Canadian organization reached out and asked if Every Contact Counts could be translated into French for their service area.

In Arizona, Close and his colleague Myles Stone, MD, MPH, published about Whiteriver Indian Hospital's contact tracing efforts in the New England Journal of Medicine COVID-19 Notes. The note, published on July 16, reported that the community's case fatality rate was 1.1%, less than half the state rate.

Whiteriver Indian Hospital has confirmed 2,300 cases of COVID-19 through its testing and contact tracing efforts. Close reported that the contact tracing teams have made contact with 100% of COVID-19 cases and have reached 90% or more of these individuals' contacts.

Close credited the hospital's success rate in part to its strong relationship with tribal leadership as well as the overall community. Since the hospital is on the reservation and regularly serves tribal members, contact tracers were familiar faces to the individuals they were visiting. In addition, the hospital and tribal leadership established a unified incident command with daily meetings when the pandemic started so they could communicate any new developments and work together to serve their community.

The peak of the pandemic came mid-June in this area. Close credited the drop in case counts to tribal leadership, who effectively put social distancing and mask wearing policies in place.

Challenges Overcome and Lessons Learned

In his service area, which Close described as an “interwoven” community, some people rely on others to bring them groceries or run other errands for them. If a large number of people are isolating, who's left to help other households? Close said, “We quickly had to pivot and work very hard with our tribal partners to put systems in place, to start aggressively providing food and essential boxes, which made a massive difference and empowered people to stay home appropriately.”

Bialek at PHF also discussed the challenges of quarantining in rural America, especially when people can't afford to take two weeks off work to stay home. Bialek wants providers to ask their COVID-positive patients, “Are you able to stay home? Are you able to afford to stay home?” If the answer is no, then the patient needs to be connected to programs like rent assistance or food banks.

In Washington, one challenge in creating Every Contact Counts was the quick turnaround time. Bekemeier said that they needed to create the training quickly, but it still needed to be good. After the training was created, the team met to discuss what went well and what didn't. Overall, Bekemeier said the process went smoothly enough that “we were still pinching ourselves.”

Her colleague Baseman added, “We just happen to have a great team that we were able to pull together.”

A really well-trained contact tracing workforce is essential.

There are challenges in over-the-phone contact tracing: tracking down contacts, getting them to answer the phone, and building enough trust so contacts feel comfortable sharing information. Baseman said contact tracers need to be persistent and empathetic. She said, “A really well-trained contact tracing workforce is essential.”

One challenge in Alaska's training initiative is the onboarding process: trying to find the balance between getting new trainees into the field quickly and making sure they're adequately prepared. Burnett said the organization has “more than enough entry-level interest” but needs more licensed professionals who can lead contact tracing teams and take part in a train-the-trainer model.

Burnett said she and her team assumed they'd be able to use the documentation software on their personal devices, but the IT department worried about information security. They decided to purchase laptops to be used for contact tracing but the laptops are on backorder. She advised other facilities to consider the technology and equipment needed for contact tracing.

But she reminded larger organizations to keep rural partners' limitations in mind. When the IT department expressed concern over using anything besides encrypted computers, Burnett said she pushed back: “You want somebody in Kotzebue, Alaska, to do this, right? You're going to have to provide them with a piece of equipment then, and you're going to have to let them use their own phone.” She added that “pushback from that rural perspective” was important to shift the IT department's thinking.

Burnett also recommended that facilities interested in helping with recruitment efforts reach out to their AHEC. Even if the AHEC itself isn't leading contact tracing initiatives, they most likely know which organizations are.

Burnett said the bureaucracy, especially working across multiple organizations, is like “these brick walls put up that you're slowly chipping away. Well, I really can confidently say that all partners involved are trying to do whatever they can to take those walls down with dynamite.”