Jun 15, 2022

Staving Off One's Mortality: Rural Kidney Health and Its Disparities

“Doc, I was told I have stage 5 kidney

disease. What happened to stages 1 through 4?”

“Doc, I was told I have stage 5 kidney

disease. What happened to stages 1 through 4?”

American Society of Nephrology (ASN) president Dr. Susan Quaggin's April message for the monthly newsletter opened with this patient question.

Experts and researchers said that the question sets up another: What's happening with kidney health in rural America?

Although kidney disease is a “silent disease” that can often be stabilized if discovered and treated, screening is not universal. Thousands of rural Americans are progressing to complete kidney failure — the final stage of kidney disease, or stage 5. Once there, they experience multiple access disparities to life-saving therapies.

Rural Patients At Risk: Common Medical Conditions Linked to Chronic Kidney Disease

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost 90% of people who have kidney disease don't even know it. Although one in three Americans are at risk for developing kidney disease, the National Kidney Foundation pointed out that “Black or African Americans are more than 3 times as likely — and Hispanics or Latinos are 1.3 times more likely — to have kidney failure compared to White Americans,” important information for populations of color in a rural America that is becoming more diverse.

Rural public health experts pointed out that risk doesn't stop with race and ethnicity. Several chronic diseases with high incidence and prevalence in rural America also cause chronic kidney disease (CKD), namely diabetes and poorly controlled high blood pressure, or hypertension. A recent CDC report indicated that these two conditions “remain the leading causes” of permanent kidney failure, accounting for 47% and 29%, respectively. Additionally, that same report found that over the past two decades, the prevalence of complete kidney failure has almost doubled.

A Rural Diabetologist: A Long-Haul Approach to Kidney Health

Family medicine practitioner Dr. Eric Johnson is a professor at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, a member of the American Diabetes Association's leadership committee on practice, and a diabetic medicine specialist, or diabetologist. In addition to his academic duties, he provides telemedicine care for patients in the largely rural state of North Dakota. He shared how he keeps his diabetic patients mindful of their condition's kidney complications and on a trajectory to achieve their best health — over the long haul.

“When I see patients early after their diagnosis, I really think the most impactful discussion is that early discussion about complications related to kidney disease,” he said, adding that the discussion also includes review of increased risk of cardiovascular and vision problems. “Not everybody with diabetes has their diabetes at the top of their list all of the time, so that fact prompts me to talk with them about how their condition takes them on a long haul. They'll need to pay attention to certain signs that will help them stay on the road and not go off in the ditch.

About one third of all adults with diabetes end up with chronic kidney disease.

“About one third of all adults with diabetes end up with chronic kidney disease,” he said. “Now, that doesn't mean that most of them end up on dialysis, but it does mean that most of them typically have stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Patients need to know that we have medications that can delay or slow the progress of their chronic kidney disease very effectively.”

Johnson said patients benefit from repetitive discussions about their kidney health and review of the “metrics of diabetes” that are tracked over a diabetic patient's lifetime.

“For persons with diabetes, there are many metrics that are really, really predictive of future complications,” he said. “It's really important that my patients understand that their A1C and their blood and urine results that track kidney complications are monitored regularly. Along with their blood pressure numbers, all those metrics influence kidney health. What we do now makes a big, big difference later when it comes to preventing progressive kidney disease.”

Kidney Function: From Healthy to Diseased to Permanent Failure

When kidneys are working at maximum efficiency, every 30 minutes, the body's entire blood volume is filtered to rid it of waste products generated by numerous chemical reactions in the body. The kidneys also maintain the body's normal fluid balance and play a strategic role in regulating blood pressure, keeping bones strong, and even influencing the production of red blood cells. When chronic disease starts decreasing the kidneys' efficiency, toxic wastes aren't filtered, fluid builds up, blood pressure rises, bones become brittle, and anemia develops.

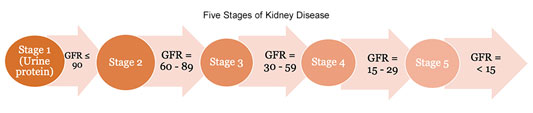

Medical conditions other than diabetes and high blood pressure can influence kidney health and rate of decline. Kidney, or renal, function is tracked over time and usually progresses through 5 stages. The stages are based on the GFR, or the glomerular filtration rate, a number calculated using a math formula that uses a blood test result, age, and gender. Stage 5 indicates permanent kidney failure and is referred to as end-stage kidney or renal disease (ESKD or ESRD).

Insights from a Rural Kidney Specialist

Experts said that many patients with kidney disease are not only unaware that medications can prevent progression to kidney failure, but don't always accept that their kidneys are not working at top efficiency. Dr. Scott Bieber is one of five nephrologists with Kootenai Health in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, that provide kidney care in the rural communities of Kellogg, Moscow, and Sandpoint as well as patients from rural eastern Washington. They use a telehealth program for their patients in Orofino and Cottonwood. He shared patient perceptions around the themes of kidney disease as a “silent disease” and disease-stabilizing medications.

“When it's a disease patients can't feel, the number one challenge is convincing patients that they have kidney disease and that it is actually a disease that can progress to kidney failure,” he said. “When I see a new patient and ask them why they are seeing me, I hear this response over and over: 'My primary care provider won't stop bothering me about getting in to see you. I'm just fine. I'm only here because they think I have a problem.'”

Once the patient expresses this perspective, Bieber said he can begin to work with patients, helping them to understand that kidney disease can't be “felt” until advanced stages, which is why it is important to monitor closely and use medications that can stabilize their kidney disease and even delay actual kidney failure.

Screen and Stabilize

Johnson and Bieber referenced medications that can stabilize kidney function. Two categories of these medications are referred to as ACEs and ARBs — angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. Other categories are the “flozins,” or “SGLT2s,” short names for sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

The names and medication categories perhaps aren't as important as what these medications do: Kidney care providers said that there are now nearly two decades of clinical studies that demonstrate these well-tolerated medications can stabilize kidney function and postpone kidney failure for years. With this proof that kidney disease can be stabilized if discovered, some public health experts noted that the current approach to screening for kidney disease — which is no screening at all — needs to be reassessed. ASN president Quaggin highlighted the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) 2022 decision to do just that. The task force has now added screening for chronic kidney disease to the list of preventive services under active consideration.

Before Rural Kidneys Fail: Stabilizing CKD

When kidneys work less efficiently, increased monitoring is required and decision-making around the start of preventive medications and other treatments has increased importance. However, for rural patients — and for the kidney doctors serving them — Bieber, who is also chair of ASN's Quality Committee, said there are management and treatment barriers ranging from lab testing to getting special infusions: for example, the expensive medication, erythropoietin, used to treat an anemia unique to kidney patients.

“I have to go out of my way to manually calculate the GFR using the latest ASN-NKF [American Society of Nephrology-National Kidney Foundation] joint task force-recommended equations because some rural labs can offer only the most basic of blood and urine testing,” he said. “They simply don't calculate the GFR for providers. Imagine how this can impact the ability of a primary care provider to detect kidney disease and get kidney care to patients early in their disease process.”

Bieber also said that the information flow around sharing lab results is also sometimes a challenge.

“Many rural hospital laboratory and clinic systems are siloed off electronically and rely solely on fax for exchange of information,” he said. “This also leads to delays in care under the best circumstances — or worse, the ball gets dropped completely.”

After Kidneys Fail: Renal Replacement Therapy

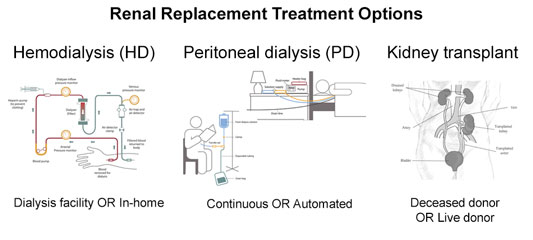

When kidneys stop, death follows — usually in a matter of days or a few weeks unless renal replacement therapy (KRT or RRT) is started. Replacement therapy is an umbrella phrase that includes treatment options for kidney failure that include hemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), and kidney transplant (KT).

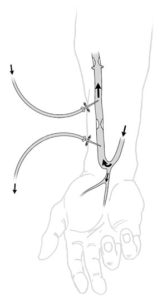

- HD directly filters the blood by placing two needles in a fistula, a connection between an artery and vein usually located in the forearm that is created by a surgical procedure. Technology is available for either in-home or in-facility dialysis.

- PD is a home treatment that requires surgical catheter placement in a patient's lower abdomen. Through this catheter flows a special fluid, called dialysate, which is instilled and then later drained, according to a schedule that is unique to every patient. PD can be done either continuously or by automated technology.

- KT is a surgical procedure where the recipient receives a deceased donor's kidney or living donor's kidney in order to take over for their non-functioning native kidneys, which are rarely removed. Due to the precision of coordinated efforts and the complexity of these procedures, kidney transplants must be performed at approved transplant centers.

Rural Dialysis: Realities and Challenges

Although modern technology has created in-home dialysis options, experts suggested that there are some challenging realities around its mechanics. For example, the sterile self-placement of two different needles — larger than the usual size used for IV fluids — into the forearm can be difficult for many patients doing home HD. Although PD doesn't require needles, it comes with its own challenges associated with the size and weight of the PD fluid bags, not to mention that, for rural patients, inclement weather or impassable roads may delay delivery of the essential dialysate fluid.

Yet there are even more challenges for rural patients with ESRD. Interim dean and professor at University of South Carolina College of Social Work Teri Browne, PhD, shared that her first job after completing her master's degree was as a dialysis social worker. Having worked in three states and now in South Carolina, her kidney disease research continues. She said when it comes to chronic kidney disease and renal replacement therapy, for rural patients, every aspect of care starts with the word “less.”

“In rural areas, there is less access to primary care providers to diagnose chronic kidney disease, less access to kidney specialists to help manage it,” she said. “This is problematic since patients in the early stages of kidney disease who have more access to all of that care can sometimes entirely postpone progression to kidney failure. Yet for rural patients? When their kidneys fail, 'less' is still the problem. Rural patients have less access to dialysis and less access to transplantation services.”

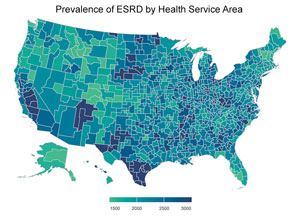

ESRD Prevalence and Cost

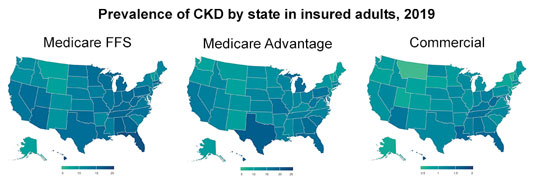

According to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2021 annual report, 2018-2019 saw an elevated prevalence of ESRD in South Carolina and Georgia's coastal plains, Lake Michigan's shoreline, the western Dakotas, southern Texas and California's Central Valley.

According to the CDC, costs for patients with chronic

kidney disease combined with the costs of care for people

with ESRD using some type of

renal replacement therapy (dialysis or transplant)

are around $124 billion. Government healthcare programs

almost solely cover ESRD expenses — including

both pediatric and adult patients. Costs are usually paid

by

Medicare, as mandated by the 1972

Public Law 92-603, the first time that Medicare

enrollment was based on a specific medical condition

rather than on age. Though yet unclear as to their impact

on rural populations, the Center for Medicare and

Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center is exploring

new care models around kidney health issues.

Starting with dialysis barriers, Browne highlighted differences by contrasting urban and rural hemodialysis centers.

“Patients usually need dialysis for three to four hours, three days a week, usually on Monday, Wednesday, Friday or on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday,” she said. “Urban center staffing can often accommodate patients with availability that includes evening hours, sometimes even overnight dialysis. Rural dialysis facilities neither have the volume of patients nor the staffing to provide that flexibility.”

Browne brought up an additional rural reality: rural dialysis center staffing difficulties that need to include a nephrologist for patient management; nurses trained in both in-facility or at-home hemodialysis and for peritoneal dialysis education, patient training, and care implementation; in addition to social workers and dieticians.

Idaho nephrologist Bieber also outlined challenges for rural dialysis, which experts pointed out is largely care that is still part of the country's fee-for-service healthcare delivery system.

Many of the dialysis challenges exist because of economies of scale.

“Many of the dialysis challenges exist because of economies of scale,” he said. “When I was working in the dialysis centers in Seattle, we had a lot of patients, we had big home programs, we had great expertise because of the volumes and the experience. When you're working in a rural dialysis center, it's completely different. You have a low volume of patients. We struggle with staff retention. Additionally, their expertise in providing home dialysis care is usually limited.”

Both Browne and Bieber suggested that even when a rural dialysis center is available, for rural patients, transportation to and from is a major problem that is reviewed in a 2019 report on dialysis transportation issues, which includes rural findings.

“In my experience, transportation is the very top, top need for rural patients with end-stage kidney disease,” Browne said but acknowledged that is true for all physical and behavioral rural health needs. “But in rural America, the lack of transportation is greatly exacerbated. Some hospital systems in rural South Carolina talk about how people literally drive their tractors to get care.”

Finding a Rural Dialysis Center

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) maintains an online search tool

— searchable by zip code — for

dialysis center locations. A

recent study also included maps detailing urban and

rural dialysis centers offering home dialysis programs.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) maintains an online search tool

— searchable by zip code — for

dialysis center locations. A

recent study also included maps detailing urban and

rural dialysis centers offering home dialysis programs.

Bieber said that transportation and other barriers to

home or in-facility dialysis care drive certain patient

choices for RRT — and also expose other rural

disparities for patients with ESRD, many of which are

outlined in a 2019

study.

“Delivering dialysis care in rural areas is just very challenging,” Bieber said. “If we don't have the staffing expertise and we don't have the infrastructure, patients end up trying to travel 50, 100, or even 200 miles for their three-times-a-week treatment. When that's their only option, sometimes they just don't choose dialysis. Or, after doing dialysis, they decide they no longer want to burden their families and friends with helping them and they choose to stop dialysis.”

That choice, Bieber emphasized, underscores yet other kidney-centric disparities.

“The choice to stop dialysis brings up even another challenge,” Bieber said. “Stopping dialysis is a complex decision and hospice care for end-stage renal disease also has barriers, including those linked to symptom management expertise and reimbursement for end of life care.”

When Rural Kidneys Have Failed: The Mortality Disparity

Going further down the rural kidney health disparity path, in a 2022 study, authors noted several rural data points:

- Nearly 240,000 rural Americans have ESRD

- Over 15,000 rural patients started dialysis in 2017, about 15% of all new dialysis starts nationwide for that year

- Rural dialysis facilities were less likely to offer home dialysis as an option

- Rural patients were more often on home dialysis, but only because they traveled to urban dialysis centers for care

- No matter where patients received dialysis care — urban or rural — rural dialysis patients have a worse mortality rate, a concerning data point because it's not directly linked to dialysis facility location

Another important consideration when evaluating kidney mortality issues is the impact that KT has on life expectancy. For some age groups with total kidney failure, KT can add almost two more decades of life over what people on dialysis can experience.

| Table 1. Approximate Expected Remaining Years of Life | |||

| ESRD Patients, 2019 |

General U.S. Population (2018) |

||

| Age | Dialysis | Transplant | |

| 40-44 | 10-11 | 28-30 | 37-40 |

| 45-49 | 9-10 | 24-26 | 32-36 |

| 50-54 | 8 | 20-22 | 28-31 |

| 55-59 | 7 | 17-19 | 24-27 |

| 60-64 | 6 | 14-16 | 20-23 |

| 65-69 | 5 | 12 | 16-19 |

| 70-74 | 4 | 10 | 13-15 |

| 75-79 | 4-5 | 8 | 10-12 |

| 80-84 | 3 | 7-8 | |

| 85+ | 3 | 4 | |

Source: U.S. Renal Data System 2021

Annual Report,

End Stage Renal Disease, Chapter 6: Mortality, Table

6.1: Expected Remaining Years of Life in ESRD and in the

General Population.

Despite modern RRT, for all patients who have non-functioning kidneys, lifespan is shortened — by decades. Life expectancy data from the USRDS 2021 annual report would indicate that if a person between the age of 40 and 44 would start a dialysis treatment, they might live another 10 years or so, compared to someone in the general population of the same age who can expect to live almost another 40 years. Improved quality of life is another important outcome resulting from transplant. For many patients, taking daily medications with infrequent follow-up appointments is preferred in contrast to the hours to and from dialysis added to the three to four hours on dialysis three times a week.

Although that person age 40 to 44 might expect to live another ten years or so if dialysis is started, if they can qualify for a KT, they might live another 20 years.

Kidney Transplant: The Greatest Rural Kidney Health Disparity?

Idaho nephrologist Bieber shared his opinion on rural patients and transplantation.

“In my mind, the highest priority for further research is the issue of transplant disparities. It's all anecdotal,” he said. “but what I see is a lot of disadvantage to being rural. It seems that the further you get from a transplant center, the lower your chance of getting a KT. We need to quantify the problem: How much more likely are you to get a transplant if you live next to a transplant center than if you live in Kellogg, Idaho?”

Kidney-pancreas transplant surgeon Dr. Joel Adler expressed similar concerns to Bieber's regarding rural patients' access to KT. As lead author on the 2022 paper outlining some of the rural issues around home dialysis, Adler and his colleagues also expressed concern that rural disparities aren't addressed in many of the recent RRT policy changes or initiatives, such as the 2019 Advancing American Kidney Health initiative, the latter with a stated goal of doubling the kidneys available for transplant by 2030.

Adler, now a team member at the new transplant program at the University of Texas at Austin, hopes to make a difference in rural transplant access gaps.

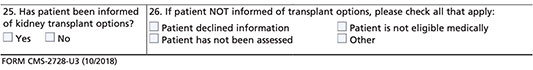

“We know there is a geographic disparity in transplantation and every transplant center handles that disparity differently,” he said. “Kidney transplantation is still underutilized and especially for eligible rural patients. We need to further look into this disparity and maybe that can start with looking more closely at 30 years of CMS data from a must-complete medical evidence form that captures a 'yes/no' as to whether transplant has been discussed.”

Experts pointed out that checking “yes” doesn't reflect either the setting, context, or content of those discussions around KT, although some research exists that might reflect those conversations. For example, a 2014 study demonstrated that “urban patients were more likely to receive supplementary information and being strongly encouraged by their nephrologists to seek transplant.” Another 2019 study suggested that rural kidney care providers' personal assessment of their patients' home support and educational levels influenced transplant referrals. Experts and advocates suggested these findings might unfairly keep patients from accessing the lowest-cost option for RRT — transplant — and not give rural patients fair access to the option that potentially offers them best longevity and quality of life.

One potential remedy, Adler suggested, is that patient education on KT benefits should be done early, using plain language, and completed in a less anecdotal, more standardized fashion. Additionally, he said he believes education around the choices of deceased donor, living donor, and preemptive KT is paramount.

Preemptive Kidney Transplant: A Recipient Shares Her Experience

Although access to KT is often blamed on organ supply shortages, some patients note that there are other barriers to that RRT option. Preemptive kidney transplant recipient Risa Simon reviewed what she described as a “profound intention shift” that occurred after decades of what she realized was passive management of her polycystic kidney disease.

“As my kidney function started to decline, my level of anxiety intensified,” Simon said. “Every six months, I'd sit in an exam room waiting for a doctor to walk in to give me the bad news about my labs. They never seemed too concerned. Even when it became clear that my kidney function was rapidly declining, they'd tell me not to worry. Discussions about transplant were almost non-existent, as there seemed to be more interest in dialysis education and 'vein mapping' so a fistula could be placed in advance of needing it. Dialysis conversations always upstaged transplant conversations, even though my doctors knew I was determined to avoid dialysis.”

Simon described how it was her own curiosity that helped her fight for what she said was her best life possible.

“It was not until I started to do my own research that I discovered the value of getting a preemptive transplant with a kidney from a living donor,” she said. “Although I developed a good understanding of the process, had the required financial resources, and had the social skills to attract several potential donors, getting to transplant was still very challenging. I thought to myself, if I was experiencing these challenges as an urban kidney patient, there's no question even greater barriers exist for rural, underserved, and minority populations. Sadly, the hurdles I experienced over a decade ago remain today.”

Simon explained that she felt the only upside to the challenges she experienced is that they became a catalyst for her wanting to help other patients. To do that, she set up her own nonprofit organization, TransplantFirst Academy. Her organization provides resources on the value of proactively seeking a living kidney donor to secure a transplant first. In addition to her nonprofit work that creates motivational patient education materials, Simon shared how she also serves as a peer mentor and advocates for kidney patient initiatives.

It's not right to have to work even harder to receive the care you deserve because you have less resources, or because of the color of your skin — or because you have transportation challenges.

“It's my hope that kidney patients will no longer face a Herculean effort to get to transplant,” she said. “It's not right to have to work even harder to receive the care you deserve because you have less resources, or because of the color of your skin — or because you have transportation challenges.

“We must empower all eligible patients, both near and far, to get promptly referred and efficiently evaluated for KT,” Simon said. 'Timing is everything, particularly when a living donor can be optimized for a preemptive transplant. Rural patients deserve to live a better and longer life — just as much as those who don't have to deal with challenging determinants, like residing in one of America's rural zip codes.”

Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Kidney Disease Initiative - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

Kidney Diseases

Health Information on Kidney Disease - American Society of Nephrology

Advocacy and Public Policy: Fact Sheets - National Kidney Foundation

Patient Information Brochures