May 29, 2019

The Power of Three: Rural Schools, Healthcare Providers, and a Rural Health Association Collaborate to Expand Primary Care Access Using School-Based Telehealth

Related Article

Virtual

Telehealth Librarians: A Closer Look at a Regional

Telehealth Resource Center's Technical Assistance

According to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's

Healthy Schools, the link is clear: healthy children

learn better — and learn more. Acknowledging

this link, organizations interested in improving the

health of rural schoolchildren must consider not just

overcoming the usual rural healthcare access challenges

— large geographic footprints, transportation

issues, insurance coverage concerns, all nested along

with the constant challenge of provider supply

— but also working to overcome the challenges a

sick student places on rural teachers, school systems,

and parents or guardians. Using a grant award from the

Federal Office of Rural Health Policy's (FORHP) Office for the

Advancement of Telehealth (OAT), the Indiana Rural

Health Association (IRHA) is “challenging

the challenges” of providing care to rural

students by creating the

Indiana Rural Schools Clinic Network (IRSCN), a rural

network dedicated to making school-based telehealth

interventions a reality.

According to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's

Healthy Schools, the link is clear: healthy children

learn better — and learn more. Acknowledging

this link, organizations interested in improving the

health of rural schoolchildren must consider not just

overcoming the usual rural healthcare access challenges

— large geographic footprints, transportation

issues, insurance coverage concerns, all nested along

with the constant challenge of provider supply

— but also working to overcome the challenges a

sick student places on rural teachers, school systems,

and parents or guardians. Using a grant award from the

Federal Office of Rural Health Policy's (FORHP) Office for the

Advancement of Telehealth (OAT), the Indiana Rural

Health Association (IRHA) is “challenging

the challenges” of providing care to rural

students by creating the

Indiana Rural Schools Clinic Network (IRSCN), a rural

network dedicated to making school-based telehealth

interventions a reality.

Kathleen

Chelminiak, project director for IRSCN's Telehealth

Network Grant Program award, shared that IRHA came to

think about school-based telehealth (SBTH) with an

earlier IRHA project involving fiber optic cable.

Kathleen

Chelminiak, project director for IRSCN's Telehealth

Network Grant Program award, shared that IRHA came to

think about school-based telehealth (SBTH) with an

earlier IRHA project involving fiber optic cable.

“Because we are an organization that is familiar to many people in rural Indiana, when internet cable was first being laid, IRHA began hearing from a few parents and superintendents who said they'd be interested in using that connectivity to have telehealth in their schools,” she said, adding that later the region's telehealth resource center and insurance payers also confirmed the need.

Chelminiak explained why the organization is also well-positioned to help advance rural telehealth in schools.

We are here with IRSCN to guide implementation of telehealth infrastructure and to help coordinate the process that links that infrastructure to our rural students and our rural providers.

“Though we're not a provider and we're not a school, we have relationships with both,” she said. “We understand that schools are busy going about education and our state's rural providers are busy caring for our rural residents. Us? We are here with IRSCN to guide implementation of telehealth infrastructure and to help coordinate the process that links that infrastructure to our rural students and our rural providers.”

Did You Know?

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “schools have direct contact with more than 95% of our nation's young people aged 5-17 years, for about six hours per day and up to 13 critical years of their social, psychological, physical, and intellectual development.”

- According to a Center for Public Education 2018 report (no longer available online), “one-half of school districts, one-third of schools, and one-fifth of students in the United States are located in rural areas.”

- According to a Rural School and Community Trust 2017 report (no longer available online), “Roughly half the nation's rural students live in just 10 states, listed from largest to smallest enrollment: Texas, North Carolina, Georgia, Ohio, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Alabama, Indiana, and Michigan.”

Chelminiak said IRSCN's motivation to promote telehealth

innovation for schoolchildren is also a response to

several state statistics.

Many of Indiana's rural counties are either partially

or completely medically underserved. According to

2016 data, the state's average of 1 primary care

physician for 1,500 people measures below the country's

best ratio of around 1 to approximately 1,000 people.

“Coming to the IRSCN project, I was astonished at the barriers to care for rural kids,” Chelminiak said. “I thought 'OK, there are providers, so, of course, kids have access to care.' When you begin to tally up all the barriers, you have a better understanding of the true numbers of children that wouldn't have healthcare access if telehealth wasn't available in their schools.”

In Greene County, Indiana, Greene County General Hospital's Rural Health Clinics use telehealth to connect White River Valley School District students with primary care providers. Read more in RHIhub's Rural Health Models & Innovations.

Aligning Telehealth Policies and Regulations

School-based telehealth requires alignment of policies and regulations. A long-standing barrier to telehealth services has been the laws regarding patient/provider relationships and medication prescribing rules. Previously, a patient/provider relationship was considered to be in place only after a face-to-face visit. With a gubernatorial signature in 2016, Indiana House Bill 1263 allowed the first telehealth visit to establish that provider/patient relationship. This law also allowed for the provider to prescribe non-controlled medications like antibiotics if needed.

After House Bill 1263 brought regulatory support to SBTH possibilities, more support followed when state agencies — Indiana's Medicaid and Managed Care Entities (MCEs) — developed policies that allowed Federally Qualified Health Clinics and Rural Health Clinics to be able to bill for SBTH services.

Important Partners: Rural School Boards

Chelminiak said the process to bring SBTH into a school starts with an invitation from a school board. She shared that the only reluctance she's noted is, on occasion, board members would be a bit skeptical until they understood that the students would see local rural medical professionals rather than a contracted urban specialty group. After clarifying who provides care, board members were “all in.” Chelminiak said it also was important for board members to learn that SBTH does not eliminate local jobs, but instead depends on local jobs, specifically the job of the school nurse.

Leaning on the Expertise of Another IRHA Grant-Funded Program

Once a school board has settled on going forward with

SBTH, Chelminiak said a broadband and internet capability

assessment follows, along with a search to match the

right telehealth equipment with the job. This is where

IRSCN has depended on expert insight from another IRHA

program, the Upper

Midwest Telehealth Resource Center (UMTRC), funded by

another OAT grant, the Regional

Telehealth Resource Center Program.

“In my opinion, UMTRC has been important for almost every aspect of our project,” Chelminiak said. “Not only did they help make sure the school's broadband was capable of providing the service, they helped us with locating the right vendor and vetting equipment for our school environments. They also help us keep on top of the most recent telehealth rulings, policies, and billing guidance for reimbursement.”

Technology Requirements for School-Based Telehealth

To link medical practices and schools, internet connections providing up and down speeds of 5 Mbps are required, speeds now common in many of Indiana's rural areas. The basic equipment list includes a tablet or laptop computer, digital stethoscope, otoscope, and dermascope, about a $16,000 investment that also includes a 2-year maintenance agreement.

Chelminiak said it was gratifying to hear provider feedback about the equipment.

“Providers are telling us that the virtual images from the equipment seem better than images from their own standard equipment or even their own naked-eye exam of the skin, eyes, or ears,” she said.

School-Based Providers: The Importance of the School Nurse

Experts acknowledge that telehealth

projects like SBTH depend on more than just the technical

aspects associated with needed broadband capability,

electronic medical record interoperability, and modern

imaging equipment: Telehealth actually depends on the

human element. For SBTH, Chelminiak said the most

important human element is the school nurse.

Experts acknowledge that telehealth

projects like SBTH depend on more than just the technical

aspects associated with needed broadband capability,

electronic medical record interoperability, and modern

imaging equipment: Telehealth actually depends on the

human element. For SBTH, Chelminiak said the most

important human element is the school nurse.

“What we've realized is 'No school nurse, no telehealth program,'” Chelminiak said. “No doubt, the school nurse is a critical part of the school-based telehealth effort.”

She also emphasized the importance of school nurses during planning and implementation stages.

What we've realized is 'No school nurse, no telehealth program.'

“The school nurses I've met are very passionate about the care their students receive and they expect only the best for their students,” she said. “Their insights have been so valuable for IRSCN's work, especially with their requests for two priorities: that telehealth doesn't slow their already busy schedules and that telehealth delivers quality medical care.”

Indiana state law dictates that public schools have healthcare access during the school day. This access can be provided by a school nurse who, by law, must be a registered nurse. However, the law also states that the school nurse may delegate certain tasks to a licensed practical nurse or unlicensed assistive personnel.

Streamlined Simplicity of a SBTH Virtual Visit

- No student in need is turned away from the SBTH network.

- If a student self-identifies as being ill or a teacher is concerned about a student's health, the school nurse proceeds with a triage protocol. If the need for a telehealth visit is identified, the SBTH workflow is implemented.

- Though prior exam permission, basic health issues, and insurance information have been collected by the school, the first step for the virtual visit is to double-check with the parent/guardian for permission to evaluate the student, along with obtaining a brief medical history update. Parents do not need to be physically present for the virtual exam.

- At this point, either the school nurse or designee enters the visit information into the software program. If needed, images of the throat, eardrum, or skin can also be uploaded, with additional live images requested by the provider. In some locations, protocol-driven school-based lab testing (for example: rapid strep, influenza, and urine problems) can be done in advance of the virtual visit.

- Entering the medical information triggers an alert at the partnering clinic site and the next available provider reviews the clinical information. Then, instead of opening the closed door of a clinic room, the provider sits down, opens the virtual connection, talks to the student with the nurse or nurse designee acting as eyes, ears, and hands for the virtual examination.

- Any needed prescriptions can be sent electronically to the family's designated pharmacy.

- The medical exam visit becomes a part of the clinic electronic record, but is not accessible by school personnel. Following HIPAA-compliant protocols, the examining provider can share the visit with the student's primary care provider if in another location.

The SBTH visit also can be a time-saver. If a child needs to go home, a parent/guardian's lost work time is decreased since the provider visit is already completed. Additionally, if a prescription is needed, often it's ready at the pharmacy with no need to wait.

Chelminiak also shared that in some schools, school staff are able to have virtual visits, a time-saver also important for teachers who need to address personal illness in a timely fashion, with early treatment potentially minimizing time away from their classrooms.

Additional Positives of SBTH

Chelminiak pointed out other important

— though more difficult to measure —

advantages of SBTH. Whether the student is 5 or 15, she

said they seem to appreciate the security that comes with

knowing they'll be able to see a doctor if they become

ill during school, sometimes asking if they can see the

“doctor on the computer.” For some

students, a virtual visit seems to get them more

interested in their own health.

Chelminiak pointed out other important

— though more difficult to measure —

advantages of SBTH. Whether the student is 5 or 15, she

said they seem to appreciate the security that comes with

knowing they'll be able to see a doctor if they become

ill during school, sometimes asking if they can see the

“doctor on the computer.” For some

students, a virtual visit seems to get them more

interested in their own health.

“We've seen some positive results when students see their own ear on a screen, or when they see what their throat looks like,” she said. “They say, 'That's my ear!' 'That's my throat!' A virtual visit almost seems like an individualized health lesson. We are even getting some reports that students seem to be more engaged in healthy behaviors after a virtual visit.”

Chelminiak also highlighted two additional benefits. The first is the overall public health impact due to early identification and sequestration of a student or staff with a contagious illness. The second is a more personal touchpoint of the SBTH protocol: If interested, parents with eligible children can be linked with local insurance navigators who'll assist with insurance plan enrollment.

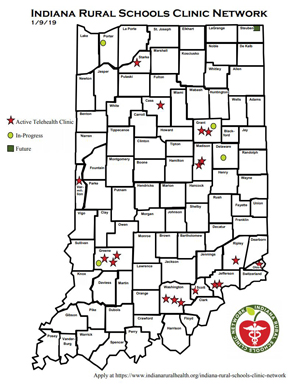

IRSCN's Future: More Schools, More Providers

Chelminiak said early implementation successes seem to have sparked a rapid word-of-mouth exchange among rural school administrators. She said IRSCN is now experiencing an “almost overwhelming” surge in the number of schools requesting information about the project. IRSCN welcomes this traffic, finding it “very, very encouraging.”

“Though there are grant limits to the total number of funded schools, we believe that we can continue to collaborate with the MCEs, other community organizations, and the schools that we've heard are interested in the program in order to get SBTH in as many schools as possible,” she said.

Since September 2016, IRSCN has assisted with SBTH implementation in 14 school systems with a total of 18 elementary, intermediate, and high schools, and collaboration with medical providers from 10 separate organizations — in addition to several behavioral health providers. Implementation for 9 more schools collaborating with additional providers and organizations is slated for the near future.

Early estimates show a range of 6 to 20 visits per month at the sites, depending on school size. Chelminiak said IRSCN partners have also shared how much they appreciate the economic benefits of SBTH, such as the cost savings in terms of transportation, parent/guardian lost wages, and preserved classroom teacher time.

Leveraging Federal Funds for SBTH

Chelminiak pointed out that FORHP's OAT grant funding has been invaluable for IRSCN's work, with funds used for SBTH implementation over a large geographic area of rural Indiana. Funds also purchase equipment that's best suited for rural schools and providers. She said her organization also believes that this funding has future implications: It better positions rural Indiana healthcare providers to offer other school-based services, such as preventive care visits and chronic disease management for conditions like asthma.

Our expansive presence allows us to reach out to the MCEs and other interested payers and organizations to engage in the work needed to reach a common goal of keeping populations healthy.

“Our expansive presence allows us to reach out to the MCEs and other interested payers and organizations to engage in the work needed to reach a common goal of keeping populations healthy,” she said. “Being in the schools and hearing their pain points — even if they're not specifically related to health — provides that invaluable perspective and deeper understanding of the needs of rural children. This perspective, combined with the provider shortages, is what makes school-based telehealth important not just for students, but for parents, schools, and for the providers who now have the satisfaction of being able to reach so many more patients.”