May 04, 2016

LGBTQ Healthcare: Building Inclusive Rural Practices

Access to

healthcare is a challenge for many in rural communities,

but for rural LGBTQ individuals, those challenges are

multiplied.

Access to

healthcare is a challenge for many in rural communities,

but for rural LGBTQ individuals, those challenges are

multiplied.

Nicole Flemmer can attest to that. For the last year and a half, Flemmer has worked in Seattle as a nurse practitioner specializing in gynecologic oncology, but previously lived in the more rural town of Walla Walla. In 2013, Flemmer launched the We Belong Project as a place to start conversations around healthcare partnerships. Flemmer commonly focuses on women of a sexual minority because of "my own experience with healthcare."

"I think I noticed [the challenges] more while living in Walla Walla. It was just very difficult there for people to know how to find providers that were knowledgeable and open and affirming," Flemmer noted.

Those conditions in Walla Walla echo the reality of small towns across America. While lesbians, gays, bisexuals, or transgendered population differ in their needs, these populations commonly suffer from healthcare disparities stemming from systematic, social disadvantages.

"We commonly group LGBTQIA together. But, each population has many different populations within each representation, so it's difficult to do sweeping generalizations," stated Flemmer. "But we do know that all of these populations put together have been historically marginalized and at times still are."

Consequences of being the "other"

Isolation from healthcare is a common reality for people in rural communities. However, sexual orientation or gender identity based-groups face another layer of isolation due to anticipated, internalized, or enacted stigmas. Each domain of stigma helps create an unruly concoction of healthcare barriers for LGBTQ individuals.

Stigma, and the fear it produces, are ingrained early on for LGBTQ individuals. A sobering report (no longer available online) from the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network found that 94 percent of rural LGBT students heard homophobic language at school, sometimes even from the school staff. Moreover, nearly 9 in 10 rural LGBTQ students had been verbally harassed, and 1 in 5 students had been physically assaulted at school because of their sexual orientation in the past year.

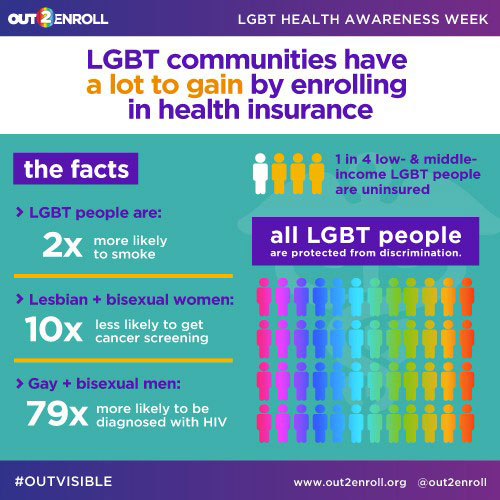

A Healthy People 2020 report (no longer available online) found LGBTQ youth are 2 to 3 times more likely to attempt suicide, more likely to be homeless, and have a higher risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). In addition, LGBTQ populations have the highest rates of tobacco, alcohol and other drug use. Transgender individuals experience a high prevalence of HIV/STD, victimization, mental health issues, and suicide. Gay and bisexual men have higher chances of major depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder compared to other men.

This mountain of health problems linked with the social force of stigma, however, remains fairly hidden at the doctor's office.

Flemmer shared her own awkward experience of coming out as a lesbian to her provider.

Sometimes, people are afraid to come out. Providers aren't asking open-ended questions and considering different alternatives or realities.

"The nurse was asking me what birth control I was using. I told her I wasn't using any. We went down this big rabbit hole of, "are you trying to get pregnant?' No. 'Are you sexually active?' Yes. And that's just not good quality of care. Sometimes, people are afraid to come out. Providers aren't asking open-ended questions and considering different alternatives or realities. Instead, the nurse just thought I was an idiot because I was having sex and not trying to get pregnant but not using any contraception. That happens very often. She was getting increasingly frustrated so I finally had to give her a break because she was never going to get there on her own."

Dr. Rob Stephenson, professor of Health Behavior and Biological Sciences at the University of Michigan, has found through research that increased levels of stigma reported by rural LGBT populations correlate with decreased levels of healthcare utilization. Failing to disclose sexual orientation or gender identity also decreases the use of healthcare services. This level of "outness" is troublesome when attempting to give appropriate care.

In a study of gay men, Stephenson noted that the only variable to impact up-to-date hepatitis vaccinations and HIV testing was disclosure from a patient to a provider.

"Not age or education or income. Nothing else mattered. All that mattered was whether or not your doctor knew you were gay," stated Stephenson.

The National LGBT Health Education Center reported that in a sample of 2,578 trans-masculine participants, enacted and anticipated stigma resulted in approximately a 40 percent increase in delaying needed urgent and preventive care. In addition, women who have sex with other women are less likely to receive preventive cancer services, even though Pap smear and mammogram recommendations do not differ based on sexual orientation. For gay and bisexual men, HIV screening as well as hepatitis A and B vaccinations are utilized less when individuals fail to disclose.

At 14, I wouldn't tell the doctor my sexual orientation because I'd know he also sees my parents. I think I'd feel the opposite if he would have said, 'well I want you to know this is confidential and I ask this of everyone.' That's a very different conversation.

Without friendly social and institutional support, rural LGBTQ individuals are more apt to internalize negative stereotypes and carry a burden of secrecy. Small social circles of rural life can be a harsh reality for people worrying that disclosure could reach family or employers.

"Everyone sees the same doctor. Every member of my family went to the same doctor," said Stephenson when describing his own rural healthcare reality. "At 14, I wouldn't tell the doctor my sexual orientation because I'd know he also sees my parents. I think I'd feel the opposite if he would have said, 'well I want you to know this is confidential and I ask this of everyone.' That's a very different conversation."

Finding a provider

Even when LGBTQ individuals are willing to share their sexual orientation or identity with their provider, finding one that is comfortable with or knowledgeable about the treatment of LGBTQ patients isn't always easy.

According to the Stanford University School of Medicine, 33 percent of responding medical schools reported that they spent zero hours on LGBTQ health-related content during clinical training. Of the doctors who did receive training on LGBTQ issues, the average time reported on the subject was five hours.

In rural areas it may be more difficult to avoid providers and staff with biases because of the limited numbers of providers available. Unfortunately, some patients seeking healthcare are turned away either overtly or more subtly despite laws prohibiting discrimination.

"The reality is some people are not comfortable with queer people. The medical community is not exclusive in these views, but there will always be [those] working in this field that don't agree with other lifestyles," noted Miria Kano, PhD, Regional Coordinating Director at the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Kano is a queer anthropologist who has been out for 27 years.

In one study co-authored by Kano, many rural participants reported that they perceived discrimination and bias in accessing healthcare, which caused them to experience fear and anxiety. Patients sometimes did not share pertinent information with their provider due to concerns about staff/provider discomfort or fears that care would be withheld. One respondent reported a nurse leaving their partner alone for hours after disclosing that they were gay.

"Awkward conversations exist on a spectrum of negative experiences all the way down to physical abuse by providers," said Flemmer. "There's been reports of women being handled roughly during their physical exams after a physician has found out that they are gay."

Transgender populations experience the most difficulty finding providers largely because there are treatments needed, such as hormone therapy, that often aren't standard with traditional care or insurance coverage. But, even the most basic clinical care of trans populations require knowledge of gender identity and sex assigned at birth. Providers may overlook prostate exams for transgender females or routine breast cancer screenings of residual breast tissue for transgendered men. Yet physicians rarely ask open-ended questions that would offer a conversation that would disclose this information.

Accessing mental health services can be especially challenging. It's been documented over and over again people of sexual minority and transgendered individuals across the board have higher rates of suicide and mental illness

Claire Bowles, who works with the Northwest College Gay Straight Alliance (GSA) in Powell, Wyoming, shared a hard reality for rural LGBTQ populations.

"It's very hard to find counseling in this area that is understanding of the LGBTQ community," stated Bowles.

Bowles noted that with such a strong traditional Mormon presence in a town of a little over 6,000 people, it's difficult to find acceptable providers.

There are only 2 counselors in a 150-mile radius that advertise that they work with the LGBTQ community.

"There are only 2 counselors in a 150-mile radius that advertise that they work with the LGBTQ community," Bowles said.

Solutions

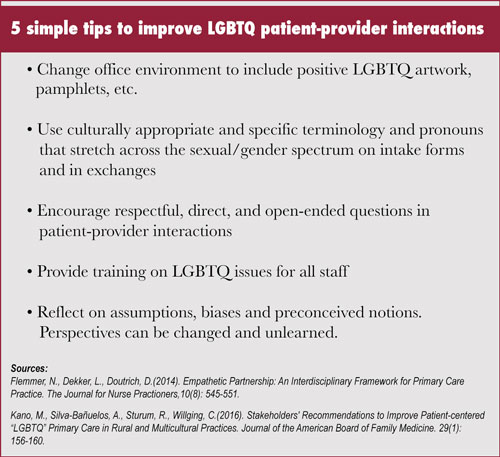

Given the challenges that rural LGBTQ individuals experience in accessing quality care, there is much that rural providers can do to ease their burden and improve the experience and care provided in their offices. Rural providers have a unique opportunity to connect with patients, as they may already share bonds with individuals in other close knit areas of rural life.

"The patients that we have been concerned with are not interested in finger wagging or saying 'you're doing a horrible job' or 'you're being discriminatory or homophobic.' It more about adding new dimensions to the wonderful care these providers are already delivering," stated Kano. Kano adds that training and dialogues between local LGBTQ populations and healthcare staff are great ways to improve the care provided.

We need to humanize a group of people often dehumanized and distanced.

"We need to humanize a group of people often dehumanized and distanced," continued Kano.

Healthcare providers can do real things right now to close the gap of healthcare disparity by familiarizing themselves in LGBTQ issues and realizing that they may have misconceptions about sexual orientation or gender identity. Training for office and healthcare staff related to cultural competency and LGBTQ healthcare needs can raise their awareness and comfort level and ultimately reduce the number of awkward encounters for patients.

It's up to the providers to start the conversations, and open-ended questions and a non-judgmental tone are powerful tools. The responsibility of disclosing behavior and identity should not fall onto the patient, but rather become a vital piece of information no different than blood pressure, temperature, or heart rate. Unfortunately, recording this vital piece of information isn't always easy, as electronic health records don't always include fields on sexual orientation and gender identity — something recent mandates from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services seek to change.

But, it's not enough to just ask a behavioral question such as "Are you having sex with men, women, or both?" Providers should know how to respond when a patient replies, "Both."

The National LGBT Health and Education Center is a great source for webinars and video training relating to LGBT health, some of which offer CME/CEU credit. For discussion guidance, the Health Professionals Advancing LGBT Equality offers simple lists of topics LGBT patients should discuss with healthcare providers.

Providers should also look at the environments healthcare is delivered in. The pronouns we assume onto people, even the boxes we check at the doctor's office can be constant reminders of "othering." Flemmer, who co-created a six-element framework to spur empathy and understanding between patients and providers, stated that changing environment is the most tangible and concrete element of the Empathetic Partnerships model.

"Make sure there are clues that patients are in an inclusive environment. Post a non-discrimination policy or have a visible Human Rights Campaign sticker. Have reading material that is inclusive of more than the heterosexual couple is another good sign. Practices can use intake forms that use open ended questions instead of 'are you married' or 'are you male or female."

Whatever it takes, communication and understanding are the tools that close disparities.