Community Health Worker-based Chronic Care Management Program

- Need: Improve healthcare access and decrease chronic disease disparities in rural Appalachia.

- Intervention: A unique community health worker-based chronic care management program, created with philanthropy support.

- Results: After a decade of use in attending to population health needs, health outcomes, healthcare costs, in 2024, the medical condition-agnostic model has a 4-year track record of financial sustainability with recent scaling to include 31 rural counties in a 3-state area of Appalachia and recent implementation in urban areas.

Evidence-level

Effective (About evidence-level criteria)Description

Americans who live in the rural areas of Appalachia have long-experienced health challenges influenced not just by healthcare access and geospatial factors, but many social determinants of health (SDOH), such as socioeconomic status and access to education. These regions have high prevalence rates of certain medical conditions and are often referred to as the "diabetes belt" or the similarly described "stroke belt."

To mitigate these disparities, public-private partnerships created a healthcare delivery model that leveraged the community health worker (CHW) skill set in a new way within a chronic care management model. The intervention was named the CHW-based chronic care management (CCM) model.

An early model became more fully developed in the Williamson Health and Wellness Center in the southern coalfields in Mingo County, West Virginia, with support from the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy and local foundations in a 2012-2015 public-private grant. When exceptionally positive results emerged, the participating organizations recognized additional potential value: leverage model outcomes within a fee-for-service structure to create a pay-for-performance incentive that would financially sustain the model.

The potential for sustainability prompted a scaling of the effort to determine if similar results could be seen with a larger program enrollment in other areas of Appalachia. Scaling efforts were positive and summarized in a 2020 academic publication.

The role of the CHW is to work with patients by "going through the door, not to the door" of their homes. Other SDOH work then naturally falls within this care model. The team meets weekly to discuss patient needs and patient care plan updates.

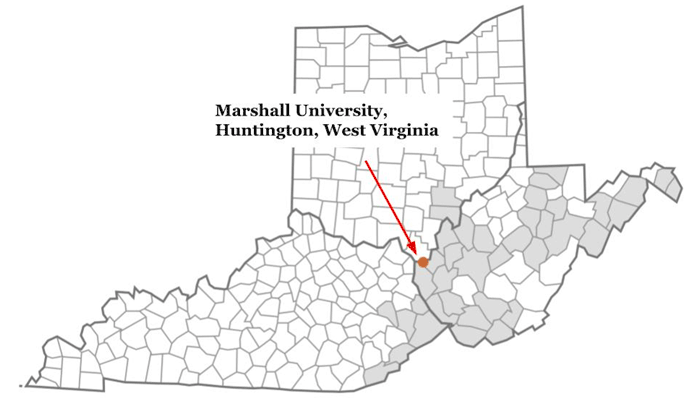

Because CHW training and job requirements are dependent on individual state laws and the employee policies of participating healthcare organizations, the model accommodates those needs by engaging an academic partner, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia. Marshall provides model sites with copyrighted standardized initial online CHW training and continuing education services. In addition to those education needs, it also provides technical assistance with billing and coding and data collection and analysis assistance.

Patient enrollment policies differ at program sites. With early model iterations, healthcare providers identified patients on the basis of their diagnosis and medical condition severity. However, as the model matured, participating payers now also play a multifaceted role in patient enrollment. Not only do they identify high risk beneficiaries for enrollment, they also offer collaborative case management, perform annual cost studies, and offer patient themselves incentives for program participation.

New to the model is expansion of the model's qualifying chronic conditions. Originally limited to diabetes, the scaled model now sees similar program benefits for patients of all ages with a variety of medical conditions, including youth with conditions such as established Type II diabetes or non-ideal weight/obesity issues, in addition to the current use for adults with most chronic medical conditions. The model has also been recently translated to include behavioral and mental health conditions, including substance use disorder.

Of note, many of the CHW-based CCM model elements have also been integrated into the Drug Free Moms and Babies program.

In addition to scaling to become medical condition-agnostic, geographic expansion has occurred. Growing from its 2020 presence in 18 rural counties in 3 states, as of July 2024, the model now engages around 50 CHWs working in 31 counties with recent implementation in several urban locations, several free clinics, and academic medical centers.

Data analysis has revealed organizations who most successfully leverage the model maintain strict adherence to model fidelity. This model fidelity leads to achieving financial sustainability, in contrast to the majority of CHW models throughout the country which have no clear and dependable funding source.

Support of the original model in Mingo County was provided by several public and private grants. Subsequent scaling efforts involved financial support from multiple organizations, including national foundations, small private and family foundations, and hospital conversion foundations as well other government grants with grant funding usually covering program startup costs. Specific philanthropy organizations included: the Appalachian Regional Commission; the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation; the Greater Kanawha Valley Foundation. the Merck Foundation's Bridging the Gap: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes initiative; the Pallottine Foundation of Buckhannon; and the Sisters Health Foundation.

Services offered

Evidence-based practices used to provide CHW services:

- Use of physician/healthcare provider champions

- Huddles

- Chronic Care Management program

CHW-based CCM team includes 3 members:

- Lead physician or advanced practice provider (APP):

- Program site nurse

- CHW

Model fidelity includes three elements:

- Provider champions

- Weekly huddles

- Weekly CHW home visits defined as "through the door, not to the door" unless CHW safety is a concern or until condition stability is reached

Specific team member roles and services are:

Lead physician or Advanced Practice Provider:

- Clinical direction and medical condition oversight, including activities such as medication reconciliation

Nurse:

- Provides clinical case management elements: appointment scheduling, referrals

- Coordination with primary care provider

CHW:

- Weekly in-home visits — through the door, not to the door — involve care plan review, medication adherence review, and update of self-management progress and goals

- During the assessment, discusses other social determinants of health that might be impacting health and overall well-being

Results

Data for the past 5 years is currently being tabulated with anticipated publication in an academic journal.

Data from previous program analysis includes:

Results for the 12-month interval/cohort = 137 patients at origin Mingo County single-site:

- Average HbA1C reduction from 10.2% to 8.5% in 12 months

- Emergency room visits decreased by 22%

- Hospitalizations decreased by 30%

Results from expanded 3-state implementation cycle from May 2017 through September 2019:

- The model's strength was demonstrated by a high adoption rate by the participating healthcare organizations in 3 Appalachian states

- Most prevalent condition: diabetes

- Cohort of 729 high-risk patients:

- 446 had both baseline and 6-month follow-up HbA1c test

- 63% (282) lowered HbA1c: mean decrease of 2.4 percentage points

- 96 patients decreased HbA1c below 10%

- For the cohort of 96 patients who lowered their HbA1c below 10%, using an assumption based on 1 less hospitalization per year, a $384,000 annual cost savings could be realized

- Based on an average of $45,000 per CHW, cost savings found by one carrier neared $5,000 per patient over a 4-month period.

The results of the 2017-2019 expansion prompted some payers to engage with FQHCs in shared savings arrangements.

The most common issues discovered to be impacting health status were social situations, literacy, and economic barriers. For example:

- Insulin expired because a refrigerator failed. The patient's financial situation precluded replacement, a situation remedied by CHW securing social service agency and faith-based organization funding for replacement.

- Missed opportunity for housing assistance caused by literacy issues, a situation remedied by CHW-assisting patient in completion of a complex form.

Due to outcomes of the CHW-based program 2017-2019, other health centers throughout Appalachia have implemented the program and now employ CHWs "beyond the scope of the grant funding." Program leaders suggest that CHWs have become a new workforce for West Virginia.

Further results for this program:

Crespo, R., Christiansen, M., Tieman, K., Wittberg, R. 2020. An Emerging Model for Community Health Worker-Based Chronic Care Management for Patients With High Health Care Costs in Rural Appalachia. Prev Chronic Dis. 17, E13.

Rural Community Health Worker Programs: Proving Value and Finding Sustainability. Rural Monitor, 24 Jul. 2024.

Rural Health Philanthropy Partnership: Leveraging Public-Private Funds to Improve Health. Rural Monitor, 31 May 2017.

In this short video, a Clay County, West Virginia CHW shares some positive outcome stories associated with of some of her work:

Replication

Replication efforts should commit to the 3 elements of model fidelity: Physician or APP champions, weekly huddles, weekly CHW visits until needs have stabilized.

Important to consider using these two hiring guidelines for CHWs:

- Community-based residence

- Ability to communicate and relate to patients with respect and empathy.

CHWs must come from the local community since, as a model, it fits in the Appalachian culture with its strong kinship networks and traditions of neighbor helping neighbor. It would be unlikely that patients would accept non-community individuals into their homes and allow frank discussions concerning health issues.

Anticipate that strong relationships will develop between the CHWs and their patients and sometimes it is best for the patient to stay permanently enrolled with decreased home visit frequency that is matched to the medical condition's severity.

Anticipate that the most intensive CHW training will occur during a shadowing experience with a nurse or experienced CHW on home visits, in addition to weekly continuing education in team huddle participation.

Using health center administration and physician champions will have a positive influence on program model adoption and patient enrollment.

If possible, consider engaging interested philanthropy partners as conveners. They often have key relationships with other change agents such as insurance carrier leadership, health policy experts, and public health researchers, especially for data analysis.

Consider building early relationships with payers. From the beginning of this project, these relationships were critical. The presence of insurance carriers at quarterly meetings contributed to early development of pilot payment models. Several began using their own data to create payment models.

Contact Information

Kim Tieman, Vice President and Health and Human Services Program DirectorClaude Worthington Benedum Foundation

ktieman@benedum.org

Topics

Appalachia

· Cardiovascular disease

· Chronic disease management

· Chronic respiratory conditions

· Community health workers

· Diabetes

· Philanthropy

· Reimbursement and payment models

· Social determinants of health

States served

Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia

Date added

May 12, 2020

Suggested citation: Rural Health Information Hub, 2024 . Community Health Worker-based Chronic Care Management Program [online]. Rural Health Information Hub. Available at: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/project-examples/1084 [Accessed 23 February 2026]

Please contact the models and innovations contact directly for the most complete and current information about this program. Summaries of models and innovations are provided by RHIhub for your convenience. The programs described are not endorsed by RHIhub or by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. Each rural community should consider whether a particular project or approach is a good match for their community’s needs and capacity. While it is sometimes possible to adapt program components to match your resources, keep in mind that changes to the program design may impact results.