Oct 17, 2018

Late Life Domestic Violence: No Such Thing as “Maturing Out” of Elder Abuse

Back to Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: Some Do's and Don'ts for Health Providers

In a 2015 study analyzing 85 rural professionals' knowledge about domestic and intimate partner violence (DV and IPV) in older residents, some participants shared a belief that individuals "mature out," or grow too old to experience violence. Late-life DV was first highlighted in 1975 when a physician shared concern regarding an injury pattern referred to as "granny-battering."

"I have personal knowledge of cases in which it has been possible to confirm that elderly patients have been battered by relatives before admission to hospital and in which there has been no doubt that the battering was deliberate…many of the elderly who 'fall down frequently, doctor' do so because they are assaulted," the provider said in the letter to the British Medical Journal.

A 2006 National Center on Elder Abuse brief (no longer available online) noted "some experts view late life domestic violence as a sub-set of the larger elder abuse problem." The brief also highlighted that, similar to the power/control issues associated with domestic abuse in younger age groups, later life domestic violence is also associated with "the abusive use of power and control by a spouse/partner or other person known to the victim." The report recommended that support services not draw fine lines between the two, instead "maximize the capacity of both systems" to meet the needs of seniors and not try to separate out domestic violence from elder abuse.

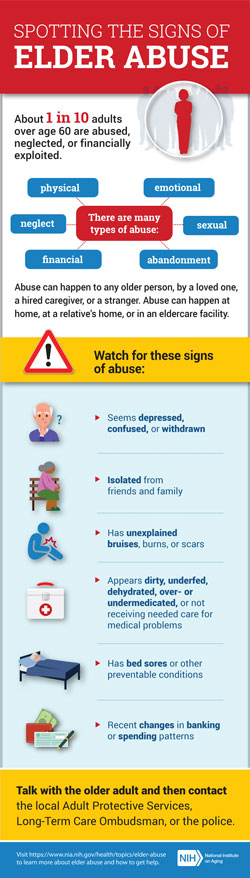

Categories of Elder Abuse and Late Life Domestic Violence

- Physical: Intentional use of physical force to cause harm.

- Sexual: Forced sexual interaction, including penetration, unwanted contact, or non-contact acts such as harassment.

- Emotional or Psychological: Verbal or nonverbal behaviors causing mental pain, fear, or distress.

- Neglect/Abandonment: Failure to meet basic needs such as food, water, shelter, clothing, hygiene, and medical care, including leaving a dependent adult alone without planning for their care.

- Financial: Illegally or improperly using an elder's money, benefits, belongings, property, or assets for someone's benefit other than the older adult.

Source: CDC's Violence Prevention Understanding Elder Abuse and the National Institute on Aging's Types of Abuse.

Screening for EA

In a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) review, authors note EA screening challenges because aging patients might try to hide abuse or be unable to articulate the abuse. Particularly troublesome for clinicians are physical findings that may — or may not — be caused by abuse. Though no gold standard for EA screening is available, there are existing tools designed for use by healthcare providers, according to the National Center on Elder Abuse.

Elder Abuse: Prevalence, Healthcare Costs, and an Expanding Elder Population

Public

health agencies note that health data around elder

abuse is difficult to gather because "elders

are afraid or unable to tell police, friends, or family

about the violence." The landmark

2010 national survey (N=5,777, age 60 and older)

looking at elder abuse derived this prevalence rate:

"Slightly more than 1 in 10 of our

community-residing, cognitively intact elderly

respondents reported experiencing some type of abuse or

potential neglect (excluding financial exploitation) in

the past year."

Public

health agencies note that health data around elder

abuse is difficult to gather because "elders

are afraid or unable to tell police, friends, or family

about the violence." The landmark

2010 national survey (N=5,777, age 60 and older)

looking at elder abuse derived this prevalence rate:

"Slightly more than 1 in 10 of our

community-residing, cognitively intact elderly

respondents reported experiencing some type of abuse or

potential neglect (excluding financial exploitation) in

the past year."

Because cognitively impaired rural or urban adults — or dependent adults with certain disabilities — can't answer surveys, other experts note that though "the true extent of elder mistreatment almost certainly exceeds the prevalence rates uncovered in direct interview surveys…taking the available evidence into consideration, estimating an overall prevalence rate of elder mistreatment of approximately 10% is reasonable for the purposes of policy development."

Considering healthcare expenditures for EA, public health researchers shared data that might have significant consequences for rural healthcare organizations typically considered to care for older, sicker patients. In a 2016 report from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, results from earlier studies indicate direct medical costs are $5.3 billion, with the financial abuse of elders amounting to over $2.6 billion annually. Why the concern? Because, the report notes, by the year 2030, 20% of people are estimated to be 65 years old and greater, in contrast to the May 2017 Census Bureau count of nearly 15%.

The report also shares a second concern: EA costs may be far-reaching due to its long-term physical and psychosocial consequences, "predictive of later disability among persons who initially displayed no disability and is associated with increased rates of emergency department utilization, increased risks for hospitalization, and increased risk for mortality."

EA Intervention

The NEJM authors also noted that "successful treatment rarely involves the swift and definitive extrication of the victim of abuse from his or her predicament with a single intervention. Instead, successful interventions in cases of elder abuse are typically interprofessional, ongoing, community-based, and resource-intensive." Especially important for rural areas then are interventions that include developing a familiarity for community resources that assist with EA assessment and disposition, like Adult Protective Services.

When abuse is identified or suspected, proper reporting channels should be identified. At the time of the NEJM publication, the authors noted 49 states (all except New York) had mandatory reporting laws that required even the suspicion of abuse to APS, law enforcement, or a regulatory agency.

Results from Iowa: Mandatory Reporting and Rural Prosecution Results

Dr. Jeanette Daly is a researcher with the University of Iowa's Department of Family Medicine. Daly said her nursing career has taken her on a trajectory through acute care, long-term care, nursing education, and on to an advanced degree allowing her to research areas intersecting with her previous clinical work in elder care.

"As clinicians, the previous department chair, Dr. Jogerst, and I both had experiences in elder abuse and we were both subject to state reporting mandates," Daly said. "Though we had to report, we never knew which cases ended up being prosecuted. So that became a research interest."

EA interventions involve a "complex set of problems that involves healthcare, social service, and the legal system," according to Daly's 2017 study aimed to provide information about prosecution results for those who report EA cases: primary care providers, community health programs involved with abuse reports, and abuse victims themselves. Daly said this has been important in Iowa, the only state with mandatory medical licensure training for dependent adult reporting.

Looking at 10 years of Iowa data (2006-2015), there were nearly 22,000 reported abuse cases. Of those, 4,000 were Adult Protective Services (APS) cases. But because the Iowa court system data is not linked to APS data, it's unclear how many of the 368 (1.6%) cases actually prosecuted were investigated by APS. Additional information from this study included a rural/urban comparison that demonstrated a "significantly higher mean" of urban prosecution. Three provider "failure to report" cases were investigated: 2 cases were dismissed and 1 individual was fined.

While only 17% of the final Iowa prosecutions were due to physical injuries, the majority (over 55%) were due to financial abuse. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control points out that financial abuse by itself costs older Americans over $2.6 billion annually, and some experts express concern regarding potential healthcare expenditure fraud also existing in this arena.

Know the numbers and realize that your knowledge impacts what you can do every day. When you are in a room of 20 older adults, recognize that there are 2 potential victims in that room.

Daly said the study offers the sole baseline data report on dependent adult abuse prosecution and she hopes it will help guide collaboration among providers, social service agencies, and attorneys, especially in rural areas. But she said her main message to providers regarding EA comes from her clinical perspective.

"Always ask, always document, and always be aware," Daly said. "Know the numbers and realize that your knowledge impacts what you can do every day. When you are in a room of 20 older adults, recognize that there are 2 potential victims in that room."