Mar 08, 2023

Perspectives on the Long of COVID: From Doomscrolling to Rural Management Strategies

COVID-19: It's an infection that still makes

headlines — whether they're read or not — and is still

touching almost every aspect of life. For those people

who actually survived an acute infection, many have been

"touched" by another condition, referred to as Long

COVID.

COVID-19: It's an infection that still makes

headlines — whether they're read or not — and is still

touching almost every aspect of life. For those people

who actually survived an acute infection, many have been

"touched" by another condition, referred to as Long

COVID.

Nathan Hale, PhD, is one of those people. Having grown up in Appalachia and currently working as a rural health researcher at East Tennessee State University (ETSU), he shared that having Long COVID himself perhaps allows him deeper insight into the condition's impact on rural communities. Hale said that as he walked through challenges that came with each day, each week, and each month of his Long COVID condition, he couldn't stop thinking about how he'd manage if he were still living in the more remote areas of Appalachia as compared to Johnson City, Tennessee, ETSU's home.

"COVID hit my family, and I wasn't spared," Hale said, referring to his pre-vaccination era acute infection. "I got pretty sick myself. At the time, I thought I had little cause to worry since I was generally pretty fit. But I began to have a few post-infection scares that rattled me."

Hale described several recurring symptoms he experienced in the months following his acute infection, such as an abnormally high heart rate following routine activities like walking up stairs and extended fatigue following mild exercise efforts. However, he said the most surprising were unpredictable occurrences of panic attacks and severe mood swings — behavioral health symptoms he'd never previously experienced.

"At some point in early 2021, I realized I had Long COVID," he said. "It was extremely disruptive. I have a pretty high level of health literacy and had an intense desire to figure this out."

Hale pointed out that during those early months, his primary information sources were online communities.

"There were a few social media platforms where discussions were happening about what we were experiencing," he said. "However, trying to understand our symptoms was difficult. I finally had to back out of these forums. Although they were helpful, reading what was happening to other folks also caused anxiety. I found myself dwelling on what happened and worrying about what might still happen. I realized it wasn't helping to just 'doomscroll' all day long."

The alternative to "doomscrolling," he said, was to look with increasing diligence for any emerging scientific literature.

"I really wanted to understand and unpack what was happening to me and, more importantly, figure out what to do about it," he said.

What's Long COVID?

According to federal public health agencies, Long COVID first received an interim working definition in February 2021, approximately one year after the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Washington state. Created by collaborations between federal agencies and the engagement of "patient groups, medical societies, and experts inside and outside the government," the current definition [no longer available online] reads:

"Long COVID is broadly defined as signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop after initial COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 infection. The signs, symptoms, and conditions are present four weeks or more after the initial phase of infection; may be multisystemic; and may present with relapsing-remitting pattern and progression or worsening over time, with the possibility of severe and life-threatening events even months or years after infection. Long COVID represents many potentially overlapping entities, likely with different biological causes and different sets of risk factors and outcomes."

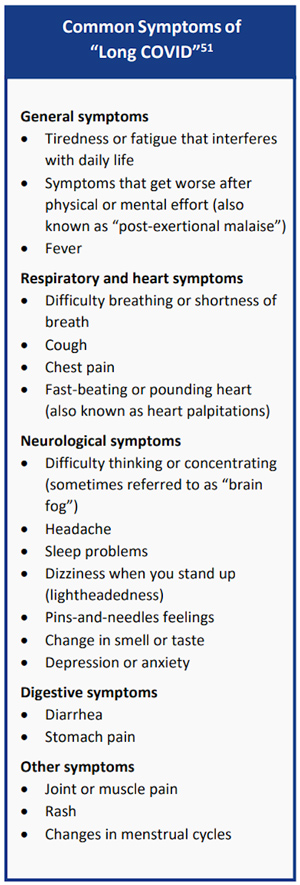

In May 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the 26 most common clinical conditions, highlighting what researchers and clinicians said is now also important for patient care: Long COVID is not just one condition, but many.

Guessing at Rural Long COVID Patient Numbers: In the Millions?

How many rural people have Long COVID? In a recent Project ECHO Long COVID and Fatiguing Illness webinar, one academic clinician translated data percentages from the CDC's online 2022 household survey and estimated that anywhere from seventeen to nineteen million American adults are currently experiencing the condition. Although no rural data was directly collected in the CDC's survey, further extrapolation to provide a rural estimate — using the most recent U.S. Census Bureau rural population percentage of 20% — suggests that around 3.6 million rural Americans may have Long COVID.

Experts do seem to agree that people like Hale who've experienced a prior COVID infection as a severe — or even a mild illness — and then go on to experience Long COVID number in the millions. Researchers also pointed out that Long COVID prevalence rates change due to ongoing research efforts around the conditions and the various efforts tracking the occurrence of those conditions, the latter often represented in two categories: people who have had Long COVID and those currently experiencing Long COVID.

A recent global review completed by researchers in the United Kingdom revealed that "45% of COVID-19 survivors, regardless of hospitalisation status, were experiencing a range of unresolved symptoms at ∼ 4 months." Other analyses reported prevalence rates varying from a low of 3%, recently reported by a large Michigan health system chart review, to 7.5%, to the CDC data from household surveys indicating around 15% having experienced Long COVID. Ongoing CDC surveys in the category of those "currently experiencing" Long COVID, demonstrated mid-February results around 6%.

What's happening at the state level? ETSU's Hale pointed out that CDC data is revealing that the highest rates of self-reported Long COVID symptoms are in states often considered quite rural. The top five states in December 2022 were Montana, Wyoming, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Alaska. In February, there was a similar rural state distribution, with West Virginia moving to the top of the lineup, followed by Wyoming, Montana, Mississippi, and Utah.

What About the Money? Rural Costs of Long COVID

For many reasons — such as the condition's only recently released definition and the lack of a structured data collection system — few reports have addressed Long COVID costs, let alone costs in rural America. However, one recent economic update suggested that for the United States as a whole the costs of lost quality of life (QOL), lost earnings, and higher medical spending nears $3.7 trillion, with 60% of that attributed to QOL costs.

Rural public health experts also emphasized that the condition will have significant economic ramifications and that there is a need to collect rural data directly since simply extrapolating numbers can be dangerously misleading, especially since urban and rural economic analyses often have few elements in common.

Michael Meit, director of the ETSU Center for Rural Health Research, pointed out that the current funding opportunities to collect rural Long COVID data are limited, or even non-existent.

"For many reasons, I think funding for any rural data collection specific to Long COVID is potentially at risk," he said. "Long COVID is a rural crisis. Even for those who hold the belief that COVID is on its way out, I think the evidence is pretty strong outlining the devastation it's leaving in its wake, like what's happening with the impact of Long COVID, as an example. There needs to be an understanding that we are going to be dealing with this for decades to come. And to understand and plan, we have to have data."

Driven by personal experience and their interests in rural populations, Hale, Meit, and several other colleagues published one of the few rural-focused academic articles on Long COVID last fall in the Journal of Rural Health. The authors concluded: "As significant investments in Long COVID research emerge, ensuring that rural areas are represented in ongoing research efforts is critical for confirming that rural communities are not left behind as diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation programs and policies are developed."

Where's Rural-Focused Long COVID Clinical Research?

Regarding the clinical aspects of Long COVID, scientists across the globe are involved with studies trying to uncover causal mechanisms. To date, one of several theoretical mechanisms causing Long COVID is that the COVID virus triggers multiple actions and reactions within the cells of the body's immune system that lead to the varied conditions of Long COVID.

Currently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has a robust research activity called RECOVER, or Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery, geared to understanding why some people fully recover from a COVID infection and why some people do not and go on to develop Long COVID.

"It's important to know that Long COVID is a real condition," said Antonello Punturieri, MD, PhD, a program officer in the Division of Lung Diseases at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which is part of NIH. "It's also important to be aware of the fact that Long COVID can occur even after a very mild acute infection and can severely affect one's quality of life."

While he noted that there is currently no cure for Long COVID conditions, anyone with lingering symptoms after they've had COVID-19 should still seek care in order for a healthcare provider to offer a diagnosis. He also pointed out that vaccination is still the key to not only preventing the severe progression of the acute viral illness but possibly also preventing Long COVID.

Punturieri also said that research is expanding, with clinical trials now launching to uncover other potential interventions that could at least prevent, if not also treat, Long COVID. Rural populations are to be included in these efforts, he said.

"We know that rural populations have been severely affected by COVID-19," he said. "With the NIH's Long COVID effort, work is being done by several research networks already in place," he added, sharing details, in particular, about the NIH grant program, the Institutional Development Award (IDeA). Some of the IDeA awardees are in a consortium led by West Virginia University and the MaineHealth Research Center. Members include 11 other NIH-funded centers in Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Puerto Rico — all engaged in research activities central to rural and other populations.

Rural Participation in NIH's Long COVID Research

Punturieri emphasized that rural patients themselves can even enroll in these research efforts after completing a series of prompts connected to online registration. For rural clinicians interested in the latest research results, he said that the RECOVER Research Review (R3) Seminar Series offers insights.

Meanwhile: Meeting Rural Long COVID Patient Needs

Ellenville, New York, with a population near 4,000, is the home of Ellenville Regional Hospital (ERH). Located in the Catskill Mountains, the hospital's swing beds are an important part of its healthcare delivery system that serves around 28,000. Hospital CEO Steven Kelley described the organization's work.

"We collaborate with upstream hospitals where available resources allow better care for our acute patients and we receive back patients with rehab needs that are better cared for with services provided by our primary hospital that's closer to home," he said.

When COVID-19 hit nearby New York City — once considered a COVID-19 "pandemic epicenter" — Kelley said ERH had its own story. He recalled the public health emergency's early impact on the dynamics of interpersonal relationships.

"We started looking at each other differently," he said, sharing anecdotes from those early weeks and months of the pandemic. "When we asked, 'What did you do this weekend?' we weren't really interested in how much fun you had. We were trying to figure out how likely you were to have been exposed to COVID. If you were in contact with too many people, we feared being close to you. Combined with the uncertainty around so many aspects of the illness in those early days, there was also so much doubt. Fear. Uncertainty. Doubt. We labeled it F.U.D."

Kelley said in those initial weeks and months, ERH's swing beds were filled with COVID patients, many with what's referred to as PICS: Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. And, as weeks and months passed and patients transitioned to discharge readiness, he said ERH's experienced teams began to notice a subset of patients with not just continued post-illness symptoms, but with similar symptom clusters.

Dr. Matthew Stupple, emergency medicine physician and ERH's medical director, clarified those early clinical observations.

"We actually were seeing two different categories of illness," Stupple said. "There were the people who'd had the prolonged ICU stays that had profound weakness, significant lung disease — either from the infection itself or as a result of the infection's impact on the heart causing cardiomyopathy. And then there was a second group of patients who were challenged by more subjective symptoms that not only lingered, but were severe enough to limit their activities."

Establishing a Long COVID Diagnosis

With his Long COVID experience, ETSU researcher Hale, along with Stupple, emphasized that for people with a prior history of acute COVID-19, either mild or severe, lingering or new symptoms should be evaluated. However, as a routine, an extensive diagnostic work-up is costly and may leave some patients without many answers.

"I worked with my primary care doctor and tests indicated my heart was structurally fine," Hale said, adding that at the time, given how little was known about Long COVID, continued diagnostic testing seemed to be costly with not much to offer in return.

"By that point, I was more interested in figuring out what I need to do to protect my nervous system and work my way back to pre-COVID fitness and activity levels," he said.

Recent research indicates that many patients undergoing comprehensive and extensive evaluations are feeling unsettled about such testing approaches. One report summarized additional perspectives: Patient respondents — 17% of which were rural — found that many medical professionals dismissed their experiences, yet still suggested "lengthy diagnostic odysseys" that offered very little in the way of treatment.

Although offering a clear disclaimer that ongoing research might change future management suggestions, professional societies and leading federal agencies, like the CDC, provide some treatment management keys: For example, acknowledging that normal laboratory and imaging findings do not invalidate symptom existence, severity, or importance of a patient's symptoms.

Another key suggests that Long COVID management can be provided by primary care providers using approaches that focus on physical, mental, and social well-being. The additional use of shared decision-making models and symptom-focused treatments are helpful, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and behavioral healthcare.

Experts also cautioned that because Long COVID is actually many conditions, it requires many management strategies for its list of disruptive symptoms. This understanding of Long COVID as many conditions should also further link to an understanding that seemingly similar conditions might have different management approaches. Take, for example, PEM, or Post-Exercise Malaise. Characterized by a delayed experience of fatigue 12 to 48 hours after activity that can last for days or even weeks, experts understand that standard exercise recommendations can actually be harmful for this condition.

Stupple shared that in New York and nearby regions, most

clinicians weren't surprised by these reports of

lingering post-COVID symptoms because they're familiar

with

Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, another

post-infection condition that often presents with a

clinical picture similar to that of Long COVID.

Fortunately for the Ellenville community, Stupple said,

ERH's experienced rehab staff recognized early on that

Long COVID had treatment options to improve physical

functional capacity and emotional well-being. Within a

short time, the hospital had an outpatient Long

COVID Physical Rehabilitation Program.

Stupple and Kelley credit their rural program's successes — in addition to the program's creation — to the hospital's rehabilitation director and physical therapist, Theresa Aversano. Aversano shared that creating a rehab program was inspired by one particular patient who was less than 50 years old, healthy, athletic, successfully self-employed, passionate about acute COVID recovery, and — after their acute infection — had previously been discharged from ERH's swing bed rehab after only several weeks of care.

"But one year later came the 'aha moment' that inspired us to do Long COVID recovery," Aversano reported.

"This same patient reappeared one year later with Long COVID symptoms," she said. "Now unable to run due to profound fatigue, shortness of breath, experiencing several other symptoms, and even unable to work, their POMA test (Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment) had actually declined to the previous level seen at the time of their original swing bed admission. We knew as rehab professionals there was a high probability that with an individualized care program, this patient could again have restored function and improved quality of life."

With the help and dedication of several ERH staff, Aversano said in short order an evidence-based program was in place. One tip she said she valued most came from an academic pulmonologist's webinar statement regarding Long COVID recovery programs.

"That pulmonologist said the key to their clinic's success was directly linked to the physical therapy clinic the patient attended," she said. "With our swing bed rehab experience, we knew with evidence-based protocols and just very basic equipment — incentive spirometers, stop watches, pedometers — we could make a big difference for our patients."

Ashima Butler, ERH's vice president & chief operating officer, also commented on the program's creation.

"When Theresa and her team began to see patients who met swing bed discharge criteria, yet had ongoing symptoms of profound fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, and anxiety, they recognized that without continued rehab interventions, some of these patients were still vulnerable," Butler said. "That gave birth to the team saying, 'OK. We need to create something on an outpatient basis to help these patients.' Additionally, we also knew our local primary care providers would need a resource for more and more patients who'd soon be coming to them seeking treatment for Long COVID."

Creating a Rural Long COVID Rehabilitation Program

The ERH program's evidence-based protocols addressed several main areas: physical endurance, upper and lower body strength, neuromuscular function, and patient education. Enrollees complete both subjective and objective assessments and attend one-on-one one-hour sessions, usually 1 to 2 sessions per week. Reassessment is performed as needed or at least every 4 weeks. Care is coded using Long COVID ICD-10 codes.

| Long COVID Recovery Program Assessment Tools | |

| Subjective measurements | Objective measurements |

|

|

Aversano emphasized the program's core elements:

Assessment and use of standardized rehab protocols paired

with good data collection to allow for objective program

evaluation.

"Our program does not require an expensive certificate and you don't need special gadgets," she said. "This program is easily replicated because it's based on tools in physical and occupational therapy's standard toolbox."

COO Butler reviewed the program results to date: More than 80% of the program's nearly 50 patients have reached their goals. Objective data collection has revealed marked improvement in measures such as the 30-second sit-to-stand test. Especially notable is their 6-Minute Walking Test results: Compared to the test's significant improvement standard of around 170 feet, their patients improve by an average of over 290 feet, a percent difference of nearly 50%.

Butler and Aversano noted that with the program's documented success and increasing enrollment, they'll add mental health services, starting with a licensed clinical social worker this year.

"We find that addressing the psychosomatic and mental health symptoms of Long COVID is also very key to the improvement in both subjective and objective measures," Aversano said, while Butler added that they know their rural program has the difficult-to-quantify benefit of delivering care that's close to home and family.

"We know our patients, we know about their families, and we know about their environment," Butler said. "That also impacts program outcomes."

With their recent data analysis revealing improvement for people with Long COVID, the ERH team is hopeful that more patients will seek treatment.

Aversano shared her personal perspective around the program's success.

There is so much reward seeing people who are feeling very dark, broken, and frustrated with Long COVID make such improvements in their quality of life and physical and mental well-being.

"There is so much reward seeing people who are feeling very dark, broken, and frustrated with Long COVID make such improvements in their quality of life and physical and mental well-being," she said.

Butler added another perspective on the organization's dedication to the population it serves.

"Here in a rural area, offering services that would otherwise not be available, we are able to change their lives with this program," she said. "I know we are a small rural hospital, but our vision is big, our offering is big, and our heart is big."

CEO Kelley said he's noted one powerful difference the program has made for their community.

"I'll just say it's really nice to get the F.U.D. out," he said.