Oct 31, 2018

Community-based Palliative Care: Scaling Access for Rural Populations

Dr. Carol Robinson, the

Community Coordinator for Making Choices

Michigan, recalls a conversation she had with

specialist at a renowned medical center on behalf of a

family acquaintance.

Dr. Carol Robinson, the

Community Coordinator for Making Choices

Michigan, recalls a conversation she had with

specialist at a renowned medical center on behalf of a

family acquaintance.

"I contacted the doctor and told him his patient was struggling at night, too stiff from Parkinson's to be able to hoist himself up so he could take his medications," she said. "So I suggested a palliative care consult and thought some physical and occupational therapy might help, too. The doctor responded immediately with 'Oh, I don't think he's to that point yet. Hearing that response, I recognized he was confusing palliative care's expert symptom management with end of life hospice care."

Robinson joins the many palliative care experts and advocates who find themselves emphasizing the difference between hospice and palliative care to healthcare providers as well as patients and families. Some advocates begin their description of palliative care by saying that though hospice care is always palliative care, palliative care is not always hospice care. Experts, like Robinson, describe palliative care as a medical specialty that provides whole person care and expert management of pain, nausea, shortness of breath, fatigue, problems sleeping, or other symptoms that negatively impact activities of daily living. Experts might also highlight additional specific differences between palliative and hospice care: palliative care uses life-sustaining services and medications and has no requirement of an imminent terminal diagnosis.

Hospice and Palliative Care Regulatory Definitions

According to an August 2017 Federal Register notice, Medicare regulations define palliative care as "patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and to facilitate patient autonomy, access to information, and choice." In addition, the notice states that Medicare's hospice definition is "palliative care for individuals with a prognosis of living 6 months or less if the terminal illness runs its normal course."

Kate Meyers, senior program officer for the California Health Care

Foundation (CHCF), has been involved with palliative

care since finishing her graduate work in public health

and public policy. In the early 2000s, Meyers worked with

a large integrated health system and teams of clinical

professionals to help develop and disseminate

evidence-based and consensus-derived practice guidelines.

I always found palliative care personally compelling. It drives at the heart of what I think healthcare should focus on: being responsive to patients' needs, their values, making sure care options are clear, especially the benefits and burdens of different treatments.

"I always found palliative care personally compelling," Meyers said. "It drives at the heart of what I think healthcare should focus on: being responsive to patients' needs, their values, making sure care options are clear, especially the benefits and burdens of different treatments."

Like cardiology, pulmonology, and other specialties, palliative care is now recognized as a separate medical specialty which has offered board certification since 2008. It has publicly available care consensus guidelines through the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. The 4th edition will be published October 2018. The specialty's early successes were largely linked to inpatient consultation, most often for cancer patients. But now experts said other research has studied palliative care delivered to patients outside a hospital setting and without a cancer diagnosis, proving the specialty's value in the areas of patient satisfaction, cost savings, and quality measures, the latter which can have unique issues when delivering community-based palliative care (CBPC) in rural areas.

"Palliative care is proven, high-quality care that typically reduces high intensity inpatient medical services while providing less costly outpatient medical services and home-based services," Meyers said. "It's time for palliative care to be recognized as a valuable approach and integrated into the care delivery system for all patients with all types of serious illness — deliberately, with reliable funding sources."

Palliative Care Challenges for Rural Populations

CHCF had done earlier work in studying palliative care service gaps and found rural Californians were lacking in accessing palliative care, especially outside of the hospital setting. Meyers said the foundation's grant, Increasing Access to Palliative Care in Rural California, has a goal of increasing access and is assisting California health plans and palliative care providers to spread community-based palliative care (CBPC) into rural areas.

In addition to access, Meyers mentioned another challenge: reimbursement. Though hospice care has been a covered benefit for many government and commercial insurance payers, palliative care is usually not.

"One of the general challenges of palliative care across the country is the lack of reliable funding mechanisms," she said. "We're working collaboratively with California health plans to get palliative care to rural patients with serious illness, and we're trying to understand funding mechanisms that can create sustainability."

Meyers pointed out that California's legislation, SB1004, mandated offering palliative care services to eligible Medi-Cal members. This regulation has created some urgency to making CBPC a covered service and a reality for rural patients, despite challenges.

There are some real challenges for rural palliative care. Everything that can be challenging about urban palliative care is just that much more difficult in rural areas.

"There are some real challenges for rural palliative care," she said. "Everything that can be challenging about urban palliative care is just that much more difficult in rural areas. For example, just finding providers. It's harder for rural programs to find clinicians with the training and experience. In addition, those providers in rural areas may find it difficult to get enough patients enrolled to cover the cost of staffing those services."

Where Are the Rural Palliative Care

Physicians?

The rural hospice and palliative care provider

distribution has been reviewed from several

perspectives in the past few years. A 2013

survey of family medicine physicians participating

in maintenance

of certification noted that overall, around 33%

(N=3609) of responding physicians provided some

palliative care. Care was mostly during home visits,

nursing home visits, or for patients on hospice. The

study noted "greater odds of reporting palliative care

provision were seen among rural versus urban

physicians," with an odds

ratio of 2.38.

A study by the George Washington University Health Workforce Institute in collaboration with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine reviewed physician workforce distribution in 2016. The report (no longer available online) included this information: "However, the 16 HPM [hospice and palliative medicine] physicians in Alaska must cover 663,000 square miles, while St. Paul's 34 physicians cover only part of a city and are augmented by the 56 additional physicians in neighboring Minneapolis. Other large, less populous states have similar issues — a concentration of HPM physicians in the limited urban centers doesn't reflect the small numbers of HPM providers in the states' remaining, largely rural, regions. Regardless of the adequacy of the overall number of physicians in a specialty, understanding and addressing maldistribution is a major policy challenge."

Kim Huffington, registered nurse and current hospice

Program Manager, has a clear understanding of the

maldistribution of workforce having moved from her rural

location in the "lower 48" to Fairbanks, Alaska, 5 years

ago. She shared that up until 2012, Fairbanks had an

all-volunteer, non-medical community hospice. Though

Fairbanks doesn't hold a rural designation, she pointed

out that "once you leave the city limits, it's rural for

miles and miles and right now we are only able to serve

our designated area." Huffington shared that her

organization has a 3-year plan to reach a CBPC model, but

providers are integral to implementation.

"We currently have one physician who wears three hats," she said. "He's the hospice medical director, the palliative care director, and long-term care director and he's only got 24 hours in a day. To offer palliative care to our outlying communities — even just phone support — we have to have another physician or nurse practitioner."

Sandy Kuhlman is a registered nurse and Executive Director for Hospice Services, Inc. & Palliative Care of Northwest Kansas in Phillipsburg, Kansas, providing care for patients in 16 counties in northwest Kansas. Thirteen of those counties have a population density of less than 6 people per square mile. This vast geographical footprint necessitates using driving speeds to calculate the organization's staffing needs since "windshield time" is a reality of providing any home-based care in rural areas. Kuhlman has worked with her company's hospice arm since 1982 and over the years, developed a yearning to also provide palliative care for patients who were "falling through the care gap" that exists between those with serious illness and chronic disease before hospice care is needed. With a substantial grant from a local foundation, Kuhlman shared they're making strides in reaching their CBPC goal, yet there are still significant barriers.

"In Kansas, if you're going to provide nursing care in the home, you must be home health licensed," she said. "Though there is a provision for hospice nurses, there is not a real clear definition for hospice nurses providing palliative care in the home. When our nurses recognize the need for palliative care, we can't provide any hands-on care, but instead we transition to more of a case management-like interaction."

A CBPC Tipping Point: Consumer Demand

Lori Bishop, MHA, BSN, RN, CHPN, has been involved in rural palliative and hospice care her entire career, joining the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in January 2018 as Vice President of Palliative and Advanced Care. She agrees with Meyers and Kuhlman that workforce shortages and payment models are "daunting rural issues." She said she notes that CBPC services now seem to be at a "tipping point" due to the growth of the aging population with serious illness and increasing numbers of patients with multiple chronic illnesses.

"If you just think of the exponential growth of the aging population alone, that's a big concern," Bishop said. "To stay on top of care needs, we need to recognize that many in our aging population will develop serious illness, especially true in rural areas. We also have to acknowledge the needs of younger individuals with multiple chronic health conditions. Palliative care needs to help meet all this demand to help these patients have a quality life."

Though experts emphasized not all patients who qualify for palliative care will accept it when offered, the benefits of this specialty are gaining popularity with consumers. Bishop said this demand is creating perhaps an even more significant tipping point: consumers who are wanting the service, but are "very confused" on what's covered and what their payment responsibilities are.

Rural and urban consumers alike are calling us asking how to get connected to palliative care services and how they should expect insurance to cover these services.

"Rural and urban consumers alike are calling us asking how to get connected to palliative care services and how they should expect insurance to cover these services," she said. "That type of demand indicates we are going to have to start reimbursing for non-hospice palliative care services in a strategic way. Right now, if the patient is homebound and qualifying for home health, the care might be provided in that circumstance. But even though a patient has completed an episode of home health, those serious illnesses and other chronic conditions are still present. We don't have any guardrails around the basic services a consumer can expect like they can expect for hospice care."

Age and Chronic Illnesses in Rural

Population

Experts said that understanding what palliative care

can bring to aging rural Americans and rural residents

with chronic health conditions needs to start with

looking at certain data around those categories.

Data from the 2010 Census allows county-level mapping for the population specifically age 65 and older. For example, the 2014 Housing Assistance Council's report mentions that about 25% of the country's senior citizens live in a rural area. A Cornell University study (N=1430) for the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging (n4a) looked at the percentage of residents age 65 and older by location: in metro core areas, 12.6%; in suburban areas 13.9%; and in rural areas, 16.8%, data that further translates into a significant percent difference between the three areas.

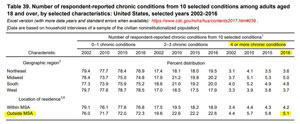

Regarding rural chronic disease patterns, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's report, Health, United States, 2017, includes a selected look at respondent-reported chronic conditions ranging from stroke, to failing kidneys, to chronic obstructive lung disease. The report included a nonmetropolitan analysis, noting that in 2016, from that list of 10 selected chronic conditions, 72% of adults 18 years and older said they had 0 to 1 of those conditions, 22% with 2 to 3 conditions, and 5.1 % with 4 or more. For the latter category, the nonmetropolitan area's distribution was almost 20% greater than the metropolitan.

Rural CBPC Initiatives Across the Country

Many rural organizations are currently involved with CBPC projects exploring care delivery mechanisms. In California, Resolution Care provides palliative care using videoconferencing technology as well as home visits for rural patients. Telemedicine has also been done in North Carolina by Four Seasons Compassion for Life, a hospice and palliative care organization that's published some of the first results in the United States on remote monitoring for CBPC. With additional funding from Duke Endowment, Four Seasons is also expanding palliative care capacity by educating rural North and South Carolina nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care providers using the Project ECHO® model, since Four Seasons is a Project ECHO palliative care hub. The Wisconsin, Washington, and North Dakota State Offices of Rural Health are involved with another CBPC project beginning with November 2017 funding from the Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies. This project is also exploring telemedicine as one of several care delivery models. These organizations will integrate CBPC services into 5 to 8 communities in each state and look at reimbursement mechanisms. Stratis Health, a nonprofit organization that specializes in healthcare quality and created the Rural Palliative Care Resource Center, is providing technical assistance for those grantees.

Scaling Access to Palliative Care

Dr. Diane Meier, founder and director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), said when rural palliative care comes to mind, she can't help but think that access for all in need is a challenge. But to that frame of reference she said she can quickly check through a list of organizations doing rural CBPC using telemedicine and remote education platforms, for example, the Resolution Care, Four Seasons, and Stratis projects. Other rural examples she included were organizations working with experts in tertiary care centers.

One example of a rural-tertiary care collaboration is Kuhlman's team in Kansas. Kuhlman said her organization's hospice work with the University of Kansas's palliative care and telemedicine teams gives her great hope as they go about further CBPC implementation and expanding opportunities with telehospice. With plans to publish those collaborative telehospice care results, she emphasized that the videoconferencing platform used for some patients brought benefits to others besides patients: consultants and family members.

"One of the hospice/palliative care certified nurses was also a wound care specialist," Kuhlman said. "She was fascinated by how well she could see the wound over the videoconferencing platform. Family members in another state also expressed their gratitude because they could dial in when the hospice nurse visited their loved one. This real-time experience is proving to be a great way for family members to be involved with care and decision-making. The same options should work for palliative care and other specialists also."

Like Kuhlman,

Meier shares optimism for integrating CBPC as part of

routine medical and specialty care. With her

organization's work on strategies to provide

palliative care access for serious illness, Meier

noted that hospital-based palliative care

programs have tripled in the past ten years, meaning

their organization's goal of "bringing palliative care

everywhere" is closer, and will continue to support

expansion working with those doing CBPC.

Like Kuhlman,

Meier shares optimism for integrating CBPC as part of

routine medical and specialty care. With her

organization's work on strategies to provide

palliative care access for serious illness, Meier

noted that hospital-based palliative care

programs have tripled in the past ten years, meaning

their organization's goal of "bringing palliative care

everywhere" is closer, and will continue to support

expansion working with those doing CBPC.

"I think the movement away from volume towards value is the best friend of scaling access to palliative care," she said. "As we work to create a community-based strategy, we need to make sure we are hearing from those rural frontline providers. My hat is off to those clinicians who are in the real world struggling to deliver high quality care to a really sick population with very low resources, poverty, and inadequate access to specialists. There is no substitute for their voice. We need to learn what they think would be most helpful, since what we think might be helpful may very well be wrong."

Additional Resources

General Resources

Chartbook on Healthy Living: Supportive and Palliative Care, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Palliative Care, National Institute on Aging

Rural Palliative Care Resource Center, Stratis Health

National Organizations

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care

Center to Advance Palliative Care

- For Patients: Get Palliative Care

- Palliative Care Provider Directory

- Mapping Community Palliative Care

Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association

National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care

National Alliance for Care at Home

- For Patients: CaringInfo