Oct 26, 2022

Rural Health Clinic Program at 45 Years: Created for Access and Still Delivering Care

In 1978, pediatrician Henry Silver, a physician leader in creating the advanced practice nurse training, wrote in an academic journal:

"Can you imagine an arrangement that permits a nurse practitioner to furnish a wide variety of diagnostic and therapeutic services under the medical direction of a physician who provides medical supervision and guidance but who need only be personally present as infrequently as every two weeks; an arrangement that allows the nurse practitioner to own the clinic in which he/she practices; and a plan whereby a clinic can operate only if it has a nurse practitioner or physician assistant on its staff? Well, that's what the rules and regulations promulgated for the implementation of the Rural Health Services Clinic Act of 1977 allow a nurse practitioner and physician assistant to do…"

The Act Silver referred to, found in

Public Law 95-210, is a reimbursement designation

earned only by a

certification process overseen by the Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Existing now for 45

years, experts reviewed the Rural Health Clinic (RHC)

program's history, pointing out that it has not been

without major challenges to its sustainability. However,

due to decades of work by many — federal agencies,

dedicated public health experts and researchers, health

policy experts, membership organizations, and, of course,

the rural healthcare delivery teams themselves — these

clinics now number nearly 5,200. And the millions of

rural patients served? Experts said that, too, is part of

the RHC story.

The Act Silver referred to, found in

Public Law 95-210, is a reimbursement designation

earned only by a

certification process overseen by the Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Existing now for 45

years, experts reviewed the Rural Health Clinic (RHC)

program's history, pointing out that it has not been

without major challenges to its sustainability. However,

due to decades of work by many — federal agencies,

dedicated public health experts and researchers, health

policy experts, membership organizations, and, of course,

the rural healthcare delivery teams themselves — these

clinics now number nearly 5,200. And the millions of

rural patients served? Experts said that, too, is part of

the RHC story.

The RHC Origin Story: It All Began When…

Health policy experts said the origin story — a story that starts actually two decades before the 1997 Critical Access Hospital designation — had several public law precursors. The first was the 1946 Hospital Survey and Construction Act, PL 79-725, well-known in rural health circles as the Hill-Burton program. According to one economic report, that program marked the federal government's first major entrance into healthcare. Additionally, it was specifically created to address access problems for war production facility workers and "for individuals in poor, rural areas of the U.S."

According to information in a 1981 rural economic report, the Hill-Burton program supported over 3,000 new facility projects and created around 6,600 additional beds: 40% were in communities with fewer than 10,000 residents — and 60% in communities with fewer than 25,000.

The second public law came nearly twenty years after Hill-Burton: PL 87-97, the 1965 Social Security Amendment Act. This landmark legislation created two government insurance programs: Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly, and Medicaid, a health insurance program for people with limited income.

Despite these two public laws creating more rural hospital beds and increasing the numbers of rural insured, Congress was still hearing about healthcare access problems in rural America. Experts offered several explanations, one of which was lack of primary care physicians in rural America.

At the time, one solution addressing that workforce issue was coming from public health reports sharing the successes of clinic models run by physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). However, those models had no chance of replication because of a policy barrier: PA and NP patient care was not reimbursed by Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial health insurers.

Lawmakers reacted. To implement these successful models came yet another landmark public policy: the Rural Health Clinic Services Act of 1977. According to a government report, this Act, "for the first time, provided Medicare and, to a lesser extent, Medicaid reimbursement for the services of physician extenders (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) working in certified clinics located in rural, medically underserved areas."

Let's Start at the Very Beginning: RHCs and Team-Based Care

As described in one academic paper, RHCs are a "vital component" of the rural healthcare safety net where primary care is provided in the medically underserved areas in rural America. Experts emphasized two unique aspects about RHC care. As Silver mentioned, the staff models must include NPs or PAs independently seeing patients and with a required intermittent review by physician supervisors: a team-based care approach. The second: Rural Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries had a designated rural point for their healthcare access.

Roger Wells, who became a physician assistant (PA) after a short career as an academic athletic trainer, practices in rural Nebraska. He described his patient care workflow — and the full spectrum of clinical duties in those early days of RHC employment.

"My first job allowed me to practice in a rural community of 2,000 where I cared for about 7,000 area patients," he said, describing the full-spectrum care done by a PA associated with an RHC. "Back then, we had family charts, not individual charts. Being on-call was constant: The only time you weren't on call was when you were actually not in town. I assisted with surgery — sometimes even called to assist when emergency surgery was needed in a nearby town where I didn't practice. I helped with C-sections and worked with the local ambulance crew.

I also worked with a physician who I had a tremendous relationship with," he said. "I learned to work arm in arm and elbow to elbow with him.

"I also worked with a physician who I had a tremendous relationship with," he said. "I learned to work arm in arm and elbow to elbow with him. We'd drink coffee every morning at about six o'clock when we'd spend about a half an hour talking about patients or problems. That was a wonderful experience."

Working Elements of the RHC Program

Rural health experts pointed out that, although rural hospitals were essential for the health and well-being of rural Americans, an RHC presence provided their service area with the three types of care. First, intervention care — the medically necessary care that can often prevent hospital admission. For example, the timely treatment of a diabetic foot infection and the education to help the patient avoid the worst complication: an amputation because the infection can no longer be cured. The second, post-discharge care — care aimed at coordinating the continued outpatient care that comes after a hospitalization for a life-threatening condition or care that actually prevents another admission. And, of course, primary care preventive care visits for children and adults. Emergency response care was also mandated. For example, treatment for seizures or antibiotics for severe infections to prevent sepsis.

Today's NPs and PAs offered their perspective on the clinical care offered in RHCs. Elizabeth Ellis, a Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) with a doctorate in nursing practice (DNP) and a previous Texas RHC owner, shared her thoughts about RHCs and the care that is intended by the program's design.

"RHCs provide accessible healthcare," Ellis said. "That's number one and foremost. Rural health clinics provide communities with access to care and a lot of resources for health promotion and wellness."

In agreement with Ellis, PA Wells shared his perspective.

"What happens in the Rural Health Clinic is actually the backbone of what should happen in medicine," he said. "The RHC is where preventive care and acute care interventions that prevent hospitalizations take place for patients with or without financial resources."

Created for Geographic Access, But Sustained by Reimbursement Policies

Financial experts and rural healthcare researchers like John Gale, a researcher with RHC expertise at the Maine Rural Health Research Center, emphasized that the RHC program answered the geographic need for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

"It's important to understand the Rural Health Clinic was not about serving solely the uninsured," he said. "It was a program targeting geographic access for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. It was really about people who couldn't get services based on where they lived."

However, Gale and other experts also said that the geographic challenges of delivering rural healthcare are inextricably linked to several rural healthcare delivery economic dictums: fixed care costs and caring for high volumes of underinsured, uninsured, and government-insured beneficiaries.

Regarding costs, having fewer patients to serve does not translate into lower costs to provide quality medical care. The fixed costs of delivering rural healthcare are not less than fixed costs in urban areas.

FNP Ellis provided an example of the second dictum — high volumes of underinsured, uninsured, and government-insured beneficiaries. Opening her clinic in a town that had not had services in over eighty years, she consistently drew patients from a seven-county area and often from three more additional counties.

We had a discounted fee schedule, but there were some that couldn't even afford that. I wasn't going to turn them away.

"My Medicaid rate was my highest reimbursement, but there were very few here covered by Medicaid," she said. "My largest population was self-pay: the farmers, the laborers, the workers, the immigrants. We had a discounted fee schedule, but there were some that couldn't even afford that. I wasn't going to turn them away. I treated them. I would think you would find any rural healthcare provider say this same thing: 'We take care of our community the best that we can and if I personally do not have the experience or the knowledge to take care of those patients, I will coordinate their care and ensure that they do get the care that they need.'"

RHC Act's Original Reimbursement Elements

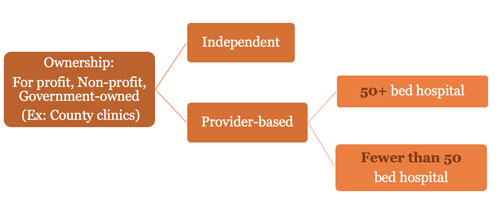

The original RHC Act allowed for an organizational structure that could be adapted by private or government (example: county-based care) organizations that were nonprofit, for-profit and located in single or multi-campus sites, or even mobile clinic locations. Its original reimbursement methodology was based on an "all-inclusive rate (AIR)," depending on whether ownership was independent or provider-based [hospital-based]. To be specifically noted: the initial regulation also stipulated that change would come: "It is the Department's intent to phase out the initial payment method beginning in March 1978…"

From No Growth…to Extreme Growth: RHCs in the 1980s-1990s

Despite the RHC program's intended benefits, five years later, in 1982, only about 450 RHCs were in existence, a surprise to many health policymakers and public health experts. RHC researcher Gale commented on the program's growth at that time.

"They expected somewhere around 1,500 clinics in the first couple of years," he said, reflecting on the fact that the actual clinic numbers were not even a third of what was expected.

Exploring why there was little program adaptation, Gale pointed to a federal report outlining four reasons that might have stunted growth:

- State provider licensing barriers: Although government insurance payers were reimbursing NP and PA services, many states had laws preventing them from practicing independently, a core element of the program for reimbursement.

- Reimbursement challenges: Federal guidelines prevented certified clinics from fully recovering incurred and otherwise allowable costs.

- "Red Tape": Costly, time-consuming federal administrative requirements negated the financial benefits of attaining an RHC designation.

- Location: Beneficiaries would see nearby physicians rather than travel to a certified RHC site that was a distance away.

However, by the mid-90s, RHC growth had exploded — by 600%.

From the original 29 RHCs in 1978 to the 450 existing in 1982, RHCs numbered almost 2,200 by early 1995. According to a 1996 federal report, half of those were created in the 18 months prior to the report. The report detailed four reasons behind RHC growth: increased access to care, reimbursement, managed care, and the certification process.

Bill Finerfrock is the cofounder and recently retired executive director of the National Association of Rural Health Clinics (NARHC). His early career put him in a front-row seat as RHCs were evolving and maturing. He said the extreme program growth raised concerns and drew the attention of federal agencies and policymakers.

"As time passed, there were things going on in the program that were inconsistent with the intent of the program," he said. "The GAO [Government Accounting Office] and the OIG [Office of the Inspector General] came out with very critical reports. But what they saw was the number of the new RHCs — particularly hospital-based clinics — that were converting an existing practice to an RHC status. Their conclusion was 'Well, the only reason you're doing that is to get the higher payment.'"

Additionally, Finerfrock said there was talk of fraud and abuse that led to conversations about eliminating the program altogether — a great concern to those who understood that descriptions of the program's benefits were missing in those reports.

"RHCs were working as intended," he said, sharing that improved Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement created sustainability despite a low-volume environment. Notably, the program was increasing the rural workforce and driving a shift in care from hospital emergency rooms to hospital-based outpatient clinics.

Rural Health Clinic Policy Influencers: The NARHC

Having served as the executive director of the National Association of Rural Health Clinics from 1992 until his retirement this year, Finerfrock offered historical perspectives in A Career of Influencing Rural Healthcare Delivery: Bill Finerfrock and the NARHC Origin Story, a story that reviews the organization's origin story, collaborative work with organizations such as NRHA, and accomplishments related to the struggles and successes of the RHC program.

Using a simple earache as an example, Finerfrock

specifically illustrated this shift.

'Come on in tomorrow' or 'Come to the walk-in clinic that's being run by our nurse practitioner or our PA who can see them.'

"If a mom with Medicaid coverage called a clinic saying that her child was complaining of an earache, a clinic might have responded that the soonest appointment was two weeks," he said, sharing that pre-RHC certification, the wait was often due to lack of appointment availability. "That mom might respond that two weeks was too long to wait, so an emergency room visit would be recommended. However, if that clinic converted to a Rural Health Clinic and they hire a PA and a NP, now they have more workforce in addition to better Medicaid reimbursement. If that same mom calls up two months later [after the clinic is RHC-certified], they might be told, 'Come on in tomorrow' or 'Come to the walk-in clinic that's being run by our nurse practitioner or our PA who can see them.' Now the clinic has the workforce to be able to care for that patient."

A Proving Ground for the Cost-Based Care Model

Finerfrock said that in addition to increasing healthcare access and recognizing the role of PAs and NPs, another hat-tip to the original RHC program legislation is to its function as a proving ground for cost-based care reimbursement.

"The RHC Act served as the testing ground and the proof that using cost-based reimbursement was a way to go for providers in low-volume, underserved communities," he said, further describing how the original RHC Act contributed to the development of two more long-standing rural healthcare delivery models.

The first model evolved from a mandated demonstration urban project embedded in the original act focusing on underserved areas. The project paired traditional Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement with grant support for the uninsured — as opposed to the RHC model with no financial support for the uninsured — and special reimbursement for the government-insured beneficiaries. This project eventually emerged as the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) model, a service delivery approach created by the 1989 Public Law 101-239. The second model adapting cost-based care reimbursement was the Critical Access Hospital (CAH) program, created by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (P.L.105-33).

Another RHC Challenge: Data Dearth

Finerfrock said that although talk about cutting the program subsided in the late 1990s, the program's reimbursement model was still undergoing scrutiny. The 1995 OIG report was succinct:

"Rural health clinics and related Medicare and Medicaid expenditures are growing at a rapid pace. However, given the lack of data on the program, we do not know what we are paying for."

Rural health researcher and past National Rural Health Association (NRHA) president, Gale has long studied RHCs, creating RHC chart books in 2003 and 2022, with a special 2023 publication planned reviewing use, services, and reimbursement.

"One of the biggest challenges over the entire duration of the program has been the availability of data and the ability to isolate data," Gale said. 'The Federally Qualified Health Center program has the Uniform Data Set that clinics must complete, but we don't have that for Rural Health Clinics. RHCs — and, more recently, Critical Access Hospitals — have argued against participating in quality improvement programs that give us data, in part, because the measures aren't specifically rural-relevant. Due to the low volume of the clinics and hospitals, those measures don't always work very well. Lack of data has really made it hard to understand the clinics. For everything from data on operations to staffing, we are using secondary data to get at much of that information. We're doing our best to figure out what secondary data is available because it can help us tell the story of what rural health clinics do."

Rural Health Clinic Research and Data

The Rural Health Research Gateway, funded

by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, provides

additional

RHC information in many journal articles, research

reports, and policy briefs.

The Rural Health Research Gateway, funded

by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, provides

additional

RHC information in many journal articles, research

reports, and policy briefs.

The Transition Years

On the heels of the RHC program having survived the earlier termination debate came new reimbursement issues as a result of Public Law 105-33, the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997. In addition to creating the Critical Access Hospital (CAH) designation, that law included a major RHC policy change. Summarized in a 1997 NRHA policy brief, its implications were described:

In order to support small rural hospitals, provider-based RHCs owned and operated by hospitals with fewer than 50 beds are exempt from the cost per visit limit. As a result, these provider-based clinics are eligible to be paid for the actual cost of care, including allocated hospital overhead. In contrast, free-standing [independent] RHCs and provider-based RHCs owned and operated by hospitals with 50 or more beds are generally paid at a rate, limited by law, that is substantially less than their actual cost.

Many rural experts suggested that these new regulations were going to need revision to either eliminate the cost per visit limits or increase the limit for independent and provider-based RHCs owned and operated by hospitals with 50 or more beds to an amount that approximates actual cost.

NARHC and NRHA's work delayed implementation of these reimbursement changes until several years later, with a final rule not published until December 2003.

Starting as NARHC's director of government affairs in 2015, Nathan Baugh talked about the historical impact of the work focused on that rule.

"In the late 90s, Bill's [Finerfrock] NARHC work was able to influence that policy, its impact on rural hospitals, and its implementation, which was then in place for the next 20 years," he said. "I know that that was a big part of the RHC history timeline."

However, in the years following the BBA changes, Baugh — now NARHC's executive director — said that RHCs began to either restructure from independent to provider-based or just leave the program. Some that withdrew remained in business as a traditional fee-for-service practice. However, some closed their doors. One report indicated that RHC closures between 2012 and 2018 "impacted over 3.86 million individuals living in rural and underserved areas."

Baugh elaborated on the fallout from closing RHCs.

"People lost access to care," he said, sharing that those closures had significant downstream impact. "The community may not be able to get a provider back because it has a downstream trickle effect where people leave and then another can't come in because it's been five or 10 years without care in that community. You lose the clinician, you lose the nurses, you lose the front office staff. They all lose their jobs."

He said there was another impact — the impact on a community's growth.

"It's hard to quantify how many folks will say, 'I want to live in a town that has a doctor," he said, suggesting that population and economic growth are stagnant or decrease when a community has no clinic access. "People are less likely to move to this area if they don't have a clinician or say, 'I want to move away to a town that at least has a clinician.'"

In this video, Finerfrock and Gale review additional historical aspects of the RHC program:

Healthcare Expenditure Growth and Another Public Law

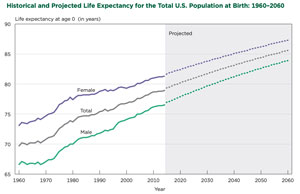

Fast forward to look at the RHC-linked events from 2003 to 2020: Those years have seen medical discoveries, new treatments, and new technologies — all contributing to increased lifespan and "healthspan," the length of a healthy life. Those changes are accompanied by significant increased growth in overall healthcare expenditures, forcing policymakers and health economics experts to review costs, including rural Medicare expenditures and personal healthcare spending trends.

In this milieu and in consideration of projected RHC reimbursement, NARHC leaders said they realized a simple fact: "The status quo for RHC reimbursement was not sustainable for either capped or uncapped RHCs." This concern for sustainability was linked to RHCs with capped — nearly flat — reimbursement rates and the disparity between those rates and those of uncapped organizations, the latter which would likely be the target of even more future scrutiny.

Describing the situation further, Finerfrock and Baugh shared that future RHC program challenges were not only coming from capped reimbursement and payment disparity but from a push for site-neutral payments, a policy of paying the same rate for a given service regardless of the care setting. For example, care delivered in the clinic or hospital setting would have the same reimbursement. Healthcare delivery systems expressed concern that this method doesn't accommodate patient needs, the different setting-specific cost structures, or the differing regulatory requirements connected with different settings.

The NARHC leaders said a resolution to those issues came on December 27, 2020, when the House and Senate enacted Public Law 166-220. Known as the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, — to date, one of the longest laws in history at over 2,100 pages — it included somewhat of a re-zeroing of RHC reimbursement. Starting in 2022, in some manner, all RHCs will have their AIR caps subject to an annual adjustment, depending on whether they existed prior to or after December 31, 2020.

| Rural Health Clinic Program Reimbursement After Consolidated Appropriations Act | ||

| Provider Type |

Enrolled BEFORE December 31, 2020 |

Enrolled AFTER December 31, 2020 |

| Independent RHC | N/A | AIR cap based on NSPL |

| Provider-based 50+ Bed | N/A | AIR cap based on NSPL |

| Provider-based <50 Beds | AIR cap at greater of facility's AIR updated annually by the MEI or NSPL | AIR cap based on NSPL |

|

Abbreviations: AIR: All Inclusive Rate, a per visit payment amount based on an RHC's yearly cost report. NSPL: National Statutory Payment Limit MEI: Medicare Economic Index |

||

Source: MedPAC Payment Basics, November 2021

Finerfrock, who's just entered retirement, said he's satisfied with the new regulations and reflected on not only these recent events but his career.

"I've been doing this for 45 years and one of the things you learn early on is it's about the art of what's possible," he said. "Passing these changes is a contributing factor to my decision to retire. I feel as though we have put the program on firm footing. I can leave knowing the program is sustainable for the next 10 years."