Apr 07, 2021

Looking at the Rural Homelessness Experience: Definitions, Data, and Solutions

Since it is clearly linked to certain

medical conditions — and intuitively linked to overall

health and well-being — housing is included in several

federal health agencies'

social determinants of health (SDOH) frameworks. The

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion points

to another housing experience linked to health and

well-being:

homelessness, described by some experts as "housing

deprivation in its most severe form."

Since it is clearly linked to certain

medical conditions — and intuitively linked to overall

health and well-being — housing is included in several

federal health agencies'

social determinants of health (SDOH) frameworks. The

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion points

to another housing experience linked to health and

well-being:

homelessness, described by some experts as "housing

deprivation in its most severe form."

Homelessness Defined

A 2018 Congressional Research Report stated that there is "no single federal definition of homelessness," although a commonly accepted definition is the experience of living in a shelter, sleeping in a place not meant for such (street, abandoned building, car), imminently at risk of losing housing, or emergently forced out of housing because of situations like domestic violence.

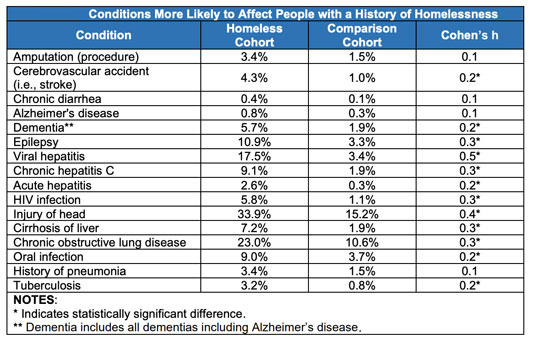

Medical Conditions and the Homelessness Experience

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office for State, Tribal, and Territorial Support (CSTLTS) points out that homelessness creates health problems that "result from various factors, such as barriers to care, lack of access to adequate food and protection, and limited resources and social services." Experts in the field of homelessness and public health said this is not only costly in terms of annual healthcare dollars — higher for those experiencing homelessness in contrast for those in more secure housing situations — but costly in terms of the negative impact on human dignity and well-being.

Starting October 2015, linking homelessness to medical conditions became easier when the United States adopted the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). This update allows rural clinicians to use codes that capture non-medical factors — like homelessness and other SDOH — associated with their patients' medical conditions. Taking advantage of this new data, a January 2021 report detailed findings from a study that reviewed a 2015-2019 data set of patients experiencing homelessness. Researchers found that people experiencing homelessness had twice the rate of ever having a head injury. They were also able to create a list of the 15 most common medical conditions and found:

- High rates of viral hepatitis

- High rates of alcohol and opioid misuse

- High rates of anemia; asthma; diabetes; and heart, kidney, and lung diseases

Understanding the Rurality of Homelessness: Definitions and Data Points

A March 2021 report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR), details the country's population experiencing homelessness. The report analyzed data collected from the 2020 point-in-time count — one-night estimates of both sheltered and unsheltered populations experiencing homelessness — during the last week in January. Collected data is also assigned to 4 respective geographic designations based on the Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics: major city, largely urban, largely suburban, and largely rural. The report emphasized that rural people experiencing homelessness may not be actually counted in rural areas, causing an undercount.

Definitions used in the report included:

- Homeless: Lacking "fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence."

- Continuums of Care (CoC): Local planning bodies that conduct the point-in-time counts are responsible for homelessness services in a geographic area, which might include a city, county, metropolitan area, or an entire state.

- Sheltered: Finding temporary residence in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe havens.

- Unsheltered: Finding residence in a public or private place not usually designated as a regular sleeping accommodation (streets, vehicles, or parks).

Some of the many rural findings include the following:

- Of all unsheltered people, largely rural CoCs had more than a third (39%) of families with children.

- Individuals in largely rural CoCs were somewhat more likely to be women (33%) compared to those in other geographic areas.

- Major cities and largely rural CoCs had the highest percentage of unaccompanied youth found staying in unsheltered locations, 53% and 50% respectively.

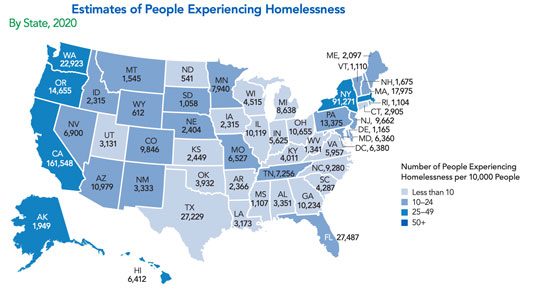

State-Level Homelessness

The 2020 pre-COVID-19 state-level data was also included in the AHAR report.

Pathways Vermont Housing First: Model for Rural Homelessness

In her video message [no longer available online] introducing the public to the 2020 AHAR results, HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge expressed concern and mentioned solutions.

"What makes these findings [2020 AHAR results] even more devastating is that they are based on data from before COVID-19 and we know the pandemic has only made the homelessness crisis worse," she said. "As a nation we have a moral responsibility to end homelessness and we know how to do it. It has been shown time and again that helping people exit homelessness quickly through permanent housing without restrictions prevents a return to homelessness."

Pathways Vermont has been using once such model, called Housing First, since 2010. Not only has the organization demonstrated success in urban and rural Vermont, but its modifications to the Housing First model make it more easily replicated in other rural areas, as described in a 2013 American Journal of Public Health article.

Pathways Vermont Assistant Director Rebeka Lawrence-Gomez described the organization's programmatic work as aiming to end homelessness by providing individuals and families access to scattered site apartments in local communities with support services delivered to the individual units or offered at an offsite location.

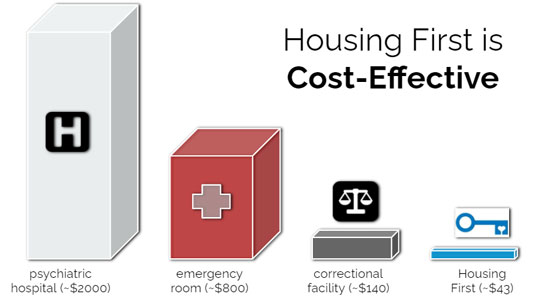

Housing First: An Evidence-Based Model to Address Homelessness

Housing First is an evidence-based cost-effective housing model endorsed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and other government agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The approach is designed to quickly connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness to permanent housing — and to do so without meeting any prerequisite admission criteria such as sobriety or treatment or service participation.

Housing First Core Components

- Few to no programmatic prerequisites to permanent housing entry

- Low barrier admission policies

- Rapid and streamlined entry into housing

- Supportive services are voluntary, but can and should be used to persistently engage tenants to ensure housing stability

- Tenants have full rights, responsibilities, and legal protections

- Practices and policies to prevent lease violations and evictions

- Applicable in a variety of housing models

Source: Housing First in Permanent Supportive Housing, HUD Exchange

Lawrence-Gomez said housing services are provided for

clients with mental health and substance use challenges

and for others who lack social supports or basic

materials for everyday living. Clients also include

veterans or parents at risk of losing their children.

The program, originating in 2010, received referrals from local shelters, community service providers, and law enforcement agencies. Pathways soon partnered with the state's department of corrections, working with individuals who were exiting incarceration since the program proved cost-effective relative to incarceration, mental health treatment, and transitional housing. In recent years, the organization's work has expanded to other communities with increased partnerships with healthcare providers.

"Another positive result from the model is that we're now working in partnership with more medical professionals," she said. "We've seen an increase in referrals from rural physical and mental healthcare providers, possibly because homelessness is not only more likely to be recognized, but recognized as a problem with a solution."

American Rescue Plan

The recently enacted American Rescue Plan "includes $5 billion for emergency housing vouchers and another $5 billion to help create housing and services for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness," according to HUD Secretary Fudge.

Lawrence-Gomez addressed some of the myths about people

experiencing homelessness, starting with the populations

most impacted by the experience.

"Yes, there are populations like those with chronic mental health challenges or substance use that are more at risk of experiencing homelessness, but it can be an experience of many — starting with anyone reading your information here," Lawrence-Gomez said. "I even include myself when I say many of us are just one unexpected, horrible situation away from experiencing homelessness. Whether it's a catastrophic weather event, a car accident, an unexpected medical event, the loss of a loved one, or a key business investment that suddenly fell through. Many who experience homelessness never viewed themselves as having to spend the summer at a campground not as a vacation, but because they lost their apartment and couldn't afford anything else. It's important to keep that perspective."

Rural Populations at Risk for Homelessness

The 2020 edition of State of Homelessness (no longer available online) from the National Alliance to End Homelessness — which includes state-level data — found that some groups experience more homelessness than others.

A 2018 report from the University of Chicago Chapin Institute, Missed Opportunities: Youth Homelessness in Rural America, found that rural youth homelessness was equal to that in urban areas, as was noted in the 2020 AHAR report. However, in rural areas, the problem was much more likely to be hidden due to activities like couch surfing. Additionally, rural youth experiencing homelessness faced more challenges in accessing social services, jobs, and education.

Lawrence-Gomez said safe housing falls under Maslow's

hierarchy of needs and provides the framework that

highlights some of the most rewarding work she

experiences with Housing First. She explained that when

basic needs aren't met, it's hard for clients to function

at a higher level when they're most concerned about, for

example, freezing to death. Once a safe place to live

becomes a stable part of someone's life, other emotional

needs surface. She said one of the most common is the

desire to connect or reconnect with family.

"For some clients, prior to accessing stable housing, they don't have the emotional ability or the resources to connect with others," she said. "I once was assisting a client who was finally able to sit at a computer. Through Facebook, that client found one of their children they hadn't connected with in years. It's amazing and powerful when those reconnections happen, whether it's with adult children or even grandchildren. Though this example is anecdotal and focused on meeting one simple emotional need, it joins so many others that stack up and make us passionate about the effectiveness of Housing First."