Nov 12, 2025

Creating Rural Physician Training Sites: Not Easy, Not Simple, But Happening With Federal Support

In rural America, the gap between need and meeting the need for healthcare workforce is widening. Specific to physicians, a recent 2022-2037 projection report found that the nonmetro physician supply across all physician specialties has a projected shortage of around 60% — compared to a 10% shortage in metro areas. Although landmark research demonstrates that rural place-based training significantly increases rural physician supply, a 2019-2020 analysis revealed that only 2% of physician training takes place in rural locations.

In addition to that evidence, some medical educators also suggest that the distribution problem is not that there are too few learners interested in serving rural populations, but that there are too few rural locations to train those interested in caring for rural and underserved populations.

Why so few training sites?

Because there are significant financial and logistical challenges that create roadblocks to expanding and creating training opportunities in rural areas, according to researchers who note that new residency startup costs in either an urban or rural area are usually over $1 million to cover personnel and time required to navigate the necessary complicated regulatory rules, rigorous academic accreditation standards, and community engagement work.

However, since 2019, financial and technical support from the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Rural Residency Planning and Development (RRPD) program — now entering its seventh cycle — is supporting 103 grantees in 36 states and Puerto Rico in their efforts to create new rural training sites. Three leaders from RRPD grantee organizations — a program coordinator, program director, and a rural hospital CEO — share their stories of the challenges, successes, and community impact linked to their new residency startup work.

Georgia South Psychiatry Residency

Any healthcare organization taking on rural-based physician training must first understand the 11- to 15-plus year timeline for training physicians and second, must master the language linked to physicians' post-medical school education. Kristoff Cohran, the Georgia South Psychiatry Residency program coordinator at Colquitt Regional Health System in Moultrie, Georgia, said that was true for him.

"When I first came to medical education, I actually thought a medical student and a medical resident were one and the same," he said. "Understanding everything involved with the training of physicians after their medical school graduation was a big learning process."

Now he said he can speak with fluency the language of graduate medicine education (GME). GME is the label for post-medical school training that happens in programs called residencies. In turn, each medical specialty, similar to the apprenticeships of other professions, uniquely standardizes its training requirements. During residency, physician trainees are referred to as residents and are supervised by more senior physicians. More advanced training happens in fellowships and those participating physicians are then referred to as fellows.

In 2019, Cohran got involved with his healthcare organization's efforts to create a psychiatry residency, the organization having experienced success with establishing a new family medicine residency program in 2016. Transitioning from another administrative leadership position, he assisted with feasibility studies and said he was energized by the complexity of the work. Eventually taking the program's coordinator position, he was able to share the backstory leading to his organization's decision to develop a psychiatry residency with residents spending 96% of their time in rural southwest Georgia.

"Across the country, there's a great need for mental health professionals in general and specifically psychiatrists, as many behavioral health services are linked to that professional," he said. "Our community health needs assessments were consistently pointing to the need for more behavioral health services because Georgia was ranking tenth nationally in its prevalence of mental health diagnoses and was forty-seventh in its need for mental health professionals. Plus, our president and CEO Jim Matney has a saying: 'See a need. Fill that need.' More behavioral health providers were that need. We recognized that to meet that need, we needed to build on the success of our family medicine residency and create another new program, this time in psychiatry."

Familiar with the research indicating that physicians more often stay rural after completing rural training, Cohran pointed out that their family medicine residency, started in 2016, gave them confidence to also address their service area's mental health needs by starting the new psychiatry residency program — even though the new program required elements differing from those needed in family medicine.

"Most people are surprised at the level of financial investment necessary to create another accredited training program," he said. "There's the need for personnel and the time required for program coordinator and physician program director recruitment. In addition, time dedicated to community engagement work — time which I believe is an absolute requisite for success. Further investment is needed for the physician faculty recruitment that's required to supervise the physician trainees. All of this must be in place before even applying for program accreditation. Obviously, these activities come with significant cost and that's where our federal funding has had the biggest impact."

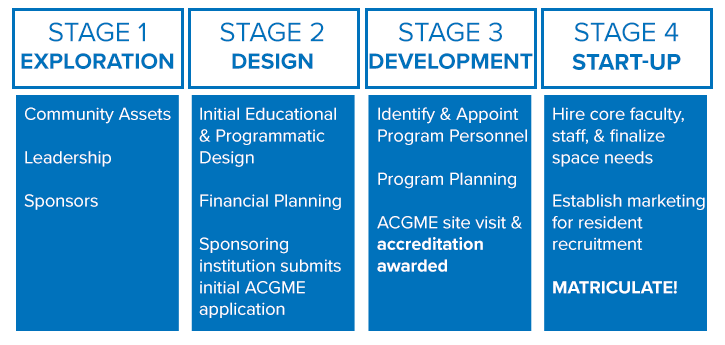

Start-Up-At-A-Glance: Residency Planning Stages

Because new rural GME programs usually follow several universal stages, the RRPD's technical assistance program created a roadmap. Some GME experts estimate that time from exploration to startup can be an average of "five or six years of patience." Also, each stage is unique to the program type and its rural location.

The current 2025 RRPD funding has two pathways. One supports primary care and "high need" specialties like family medicine, internal medicine, preventive medicine, psychiatry, general surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. The second supports maternal health and obstetrics.

Cohran shared community engagement specifics that were needed to elevate both the medical and non-medical value of an additional physician training program.

"Because of my background in economic growth and development, it was easy to see what new medical training programs would bring to the community's economic base," he said, adding that this was also apparent from their recent experience with the opening of an osteopathic medical school branch in Moultrie. "Our community recognized that it needed to modernize with expansion efforts in housing, restaurants, and shopping that might better accommodate the people these programs would bring to our community."

However, in addition to his community's business sector, he also emphasized his belief that the community culture is so unique that any newcomer would find their community attractive, adding that Colquitt County's population of about 50,000 people speak nearly 20 different languages.

"Another unique aspect of our culture here is that we are just nice — and nice for no reason," he said. "Nice without any expectation of some secondary gain."

As a member of the first cohort of RRPD grantees in 2019, much of the program exploration, design, and development stages happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the associated challenges of that time, Georgia South Psychiatry Residency's initial recruitment efforts filled its new rural program's three physician training positions in 2022, an accomplishment that's continued.

Cohran said he believes their successful fill rate is linked to the fact that their healthcare system and their community is attractive to this generation of medical school graduates who seem to have desire for rural training.

"The most frequent interview applicant feedback we receive is this: 'I was pleasantly surprised at what you and your program have to offer. What you have here is special,'" he said. "Even during interviews, we see changes in facial expressions and body language when we talk about what our program and what our community offer. Here at Colquitt Regional, we know we have transitioned from a healthcare system of excellence to a teaching healthcare system of excellence."

Madras, Oregon: Three Sisters Rural Track Program

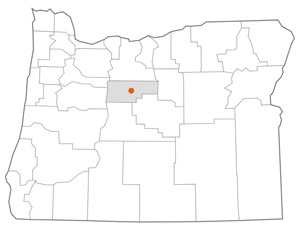

In contrast to the Georgia psychiatry program's association with a rural healthcare system, on the other side of the country is the Three Sisters Rural Track Program in Madras, Oregon, a new family medicine program linked to a university, the Oregon Health & Science University's (OHSU) Portland-based family medicine residency.

Having achieved the special accreditation designation as a Rural Track Program (RTP), it offers both urban-based training in its first year followed by the mandatory 50% or more time in a rural area. The Three Sisters residents spend their first year in Portland with the following two years in central Oregon where they continue with more obstetrical training that's paired with the diverse family medicine care experiences at St. Charles Madras, a Critical Access Hospital; the Mosaic Community Health's Federally Qualified Health Center; and the Warm Springs Indian Health Service.

St. Charles family medicine physician Dr. Jinnell Lewis is the Three Sisters program director, a position that must be filled by a physician. Growing up in urban Washington state, Lewis said she'd always been "called" to the practice of obstetrics (OB). However, once she discovered that with family medicine she could do OB and "not have to give up" primary care of all age groups, family medicine with an OB practice became her way of life.

Lewis completed her residency at OHSU's Cascades East Family Medicine in Klamath Falls, Oregon, and moved to Madras, now working with St. Charles Health System for over 10 years. After establishing her practice in Madras, Lewis said her OHSU mentors had persistently reached out about expanding Madras's medical education offerings from just medical student rotations to further include GME and resident training. She said the 2022 FORHP grant award made that a reality with the Three Sisters program and she agreed to be the RTP program director. After several years of intense and complex planning and start-up activities, the program welcomed its first cohort of residents in August 2025.

In her position as a local practicing physician and healthcare leader, Lewis said much of her community's feedback on the new residency has come from her patients and hospital staff.

"As program director, my activities with the program take time out of the office and some of my patients are frustrated with my time away," she said. "However, once they learn what's happening, they seem to gain a lot of pride in that fact and tell others in the community that I'm working to bring more doctors to Madras. Because I've always had medical students — so often that sometimes my patients will actually ask me, 'Where's your medical student? Where's your learner?' — with this new understanding that a residency program actually brings new physicians here that might stay after their training, they're very excited."

Lewis shared that the excitement isn't stopping at the clinic doors. The hospital staff are having their say, too.

"Now that we have accreditation, we've had some residents come over for elective rotations and the hospital's nursing staff have loved those experiences," she said. "Understand that those experiences are different for our nurses who are used to medical students. Because residents are physicians who can write orders and do patient care at an advanced level, the nursing staff asks me, 'When is it that we're going to have our own residents? We want our own here, right now, full time!' Also, the nursing staff tell me they're realizing how much they're loving the teaching and being a part of resident education."

In addition to the patients and hospital staff engagement, Lewis said community leaders, too, are engaged.

"I've been doing a lot of outreach with the public health department, our city government organizations, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs tribal council," she said. "In addition, I've also reached out to the Central Oregon Health Council and the other advocacy groups. In general, everyone is positive. The city representatives see value in new people that might have partners and family with job skills that'll further grow our community. Specifically, our county commissioners were supportive as they see the residency as a way to improve our county health outcomes that are, in part, linked to access to care and travel time to nearest provider."

Because OHSU received the funding award, Lewis said she became acquainted with the financial complexities around the RTP startup connected to an urban-based program. Despite those complexities, she commented that her OHSU mentors and colleagues — who've always been rural medicine advocates — are committed to making sure the program is on track.

On the theme of complexities, she offered that particularly valuable was her grant-supported participation in a fellowship dedicated to leadership development for new program directors. She said the training has been invaluable because it provided her with skills that she now leverages in her everyday work — work that always seems to include situations never before experienced. Also, she said it's connected her to a supportive network of new and experienced program directors.

However, Lewis said there is an important remaining challenge and one that is common to many of the RRPD grantees: faculty recruitment.

"Physician recruitment in rural areas is hard enough," she said. "I did think that having a teaching role or academic appointment might improve recruitment, yet we are still recruiting."

Hannibal, Missouri: A Rural Hospital CEO's Perspective on RRPD

Located on the Mississippi River in rural Marion County, Hannibal, Missouri, is home to a well-known author and several movie and television characters. Its hospital, Hannibal Regional Healthcare System (HRHS), is a 120-year-old nonprofit rural healthcare system with a 99-bed Sole Community Hospital that serves nearly 150,000 residents living in the 13 counties located in the adjacent three states.

Todd Ahrens, one of the longest serving rural hospital CEOs in the country, spoke about how the RRPD grant support is impacting their organization's workforce future as well as the communities they serve.

"For several years, our workforce development efforts have included hospital-based medical student experiences," he said. "Many of these students grew up in Hannibal or in our surrounding counties, so developing a residency program for our community and our region in Northeast Missouri was really the next natural step in retaining and growing this potential physician workforce."

However, noting that a CEO understands that new residencies will eventually bring an immediate increase in local physician access with reimbursement for the care residents provide under supervision, the lag time between the startup and revenue production becomes a substantial financial challenge. This is where, Ahrens said, their 2023 RRPD funding award has been key.

"Rural CEOs are very aware of their rural hospital's thin operating margins," he said. "It can be difficult to get a board's support for a new project like a medical residency when there is no anticipated revenue for several years. For us, the RRPD award lessened those challenging financial edges that come with the years it takes to get the program going."

HRHS is one of four RRPD grantees whose grant application was specific for an internal medicine (IM) residency. Recently accredited, it will now join the 30 other rural-based IM residencies on the list of the 700-plus IM residencies in the country. Ahrens shared more about HRHS's decision to undertake the creation of not just a new residency, but specifically a new internal medicine residency.

"About a decade ago, our board and our organization made a commitment to making sure healthcare was local to our community," he said, noting that urban-based healthcare in either St. Louis or Columbia was well over 100 miles away. "We recognized if local care was to happen, we needed medical subspecialty providers here to do it. That approach also included having enough primary care providers, like family medicine and internal medicine. Although we knew that an internal medicine residency might be a bit more difficult to start, it best met our workforce needs, especially because we are already using a hospital internal medicine model for a lot of our inpatient care."

What Is Internal Medicine?

Fifty-three million people over age 18 live in rural America, and primary care physicians are needed to care for them. Although both family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM) physicians care for adults, FM is considered to provide a broader scope of care for every age group. Differing from FM, IM training has more dedicated hospital-based training. Supervision is provided by internists — the name for physicians who are generalists in internal medicine — along with cardiologists, gastroenterologists, nephrologists, and other IM subspecialties considered core to general IM training. Additionally, if a new MD has a final career choice of one of about two dozen internal medicine subspecialties, completing an internal medicine residency fits the prerequisites.

Ahrens said that there were other organizational philosophies that he believed influenced their residency start-up decision.

"We don't believe that just doing things the way we've always done them for the past 20 years is always successful strategy, so we were also willing to go out there and do something that other organizations our size maybe wouldn't be willing to try," he said, also noting it would build on their additional place-based rural healthcare workforce development work — efforts often referred to as "grow your own."

"Many of the medical students working with us have already heard about our internal medicine residency program plans and are making inquiries around its anticipated start date in July 2026," he said.

"However, we also know we're not going to keep them after they've finished their residency training if they don't enjoy the community. This is where the CEO perspective must include the recognition that your organization is more than just your community's healthcare delivery system. You are another major pillar in the community along with business leaders, local government agencies, and many other organizations. This position and perspective showed in innumerable letters of support backing our grant application. Everyone seemed to understand that this new program has the potential to bring new people in and keep them — and that the retention will not just influence our medical care but help drive economic development in Hannibal and its surrounding communities."

Ahrens shared additional tips for other rural C-suite leadership teams who might be considering a rural residency start-up.

"If you're going to make the leap into starting a new residency program, you've got to be honest about your readiness to do this," he said. "You have to do your homework. You can't just watch a YouTube video and understand what you're undertaking. CEOs will need to lean into their people and be confident in their organization's ability to do this thing because any lack of confidence will take on a life of its own. Boards have to be involved, and they need to understand the financial commitment and that it's a lengthy process from initial discussions to finally having residents available to provide care for your community."

"However, when you're the CEO, at the end of the day, you can also think this: This will benefit my hospital, my organization, my community, and the community's viability. We're growing this for everybody. I think there's a lot of rural CEOs and community organizations who are smart enough to see that and make the decision to move forward."