Apr 18, 2018

Social Determinants of Health: Transforming the Buzz Phrase to a Rural Action Item

"What's

next?" This is the two-word question rural

healthcare innovators think about every day. For some

innovators, a partial answer to that question might be

population health management. For others, a top priority

might be addressing social

determinants of health (SDOH), a well-used, popular

phrase perhaps still searching for its niche. Assisting

in that search, academicians and rural health

organizations are using social risk assessments to

convert determinants from a buzz phrase to a rural

healthcare delivery action item.

"What's

next?" This is the two-word question rural

healthcare innovators think about every day. For some

innovators, a partial answer to that question might be

population health management. For others, a top priority

might be addressing social

determinants of health (SDOH), a well-used, popular

phrase perhaps still searching for its niche. Assisting

in that search, academicians and rural health

organizations are using social risk assessments to

convert determinants from a buzz phrase to a rural

healthcare delivery action item.

Social Determinants: Collegiate Version

Understanding where social determinants fit into health outcomes should be standard curriculum for public health education, according to Mercer University's Dr. Cheryl Gaddis.

"These students will be designing future public health programs and they need to understand that they'll be involved with people who are doing everything they are supposed to be doing, engaging in all the appropriate behaviors, but who will still face poor health due to those social determinant factors preventing them from achieving good health outcomes," Gaddis said.

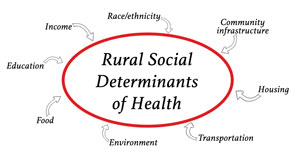

Gaddis, an Assistant Professor in her university's College of Health Professions and an education specialist for curriculum development for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, points to the definition used by World Health Organization: "The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age." She draws on her early career boots-on-the-ground experience as a health promotion coordinator for 13 Georgia counties, the majority mostly rural, to make clear to students that a definition is just a starting point for really understanding the nuances of determinants.

"I encourage students to think outside the literal definition in terms of determinants that might be "unfair and avoidable," she said, explaining that an example of "unfair" might be represented by being "born into poverty."

In contrast to the unfair economic circumstances of birth, Gaddis said she believes that growing up with barriers to healthcare access or educational opportunities can be "avoidable" health determinants with policy change or resource redistribution. She shared that equally important is making sure students understand the full spectrum of social determinants throughout society.

"No matter what hierarchical level you're on, determinants will impact your health," Gaddis said. "For example, you might have a high salary that purchases needed healthcare access and health interventions, but that salary might be from a high stress job, allowing no time for physical activity, and little family time. Stress, inactivity, perhaps even social isolation might impact their health more than having a high income and an advanced education."

A Historical Look at Social Determinants

In a 2010 University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute working paper on health determinants, the authors share that from the 1930s through the 40s, the big health push was changing unhealthy living environments using public health initiatives geared to sanitation issues and safety laws since infections and accidents were killing Americans.

Moving into the next several decades, the 1950s and 60s saw heart problems and cancer as the most common diseases with the highest mortality. Clinical preventive services became the public health approach to these illnesses. Screening initiatives were pushed to the forefront.

With the arrival of the 1970s and on through the 90s, groundbreaking research highlighted the health impact of smoking, diet, exercise, and other personal behaviors. With this cumulative research, public health experts now understood that these three factors — environment, clinical care, personal behaviors — seemed only part of what impacts health.

Since the late 90s, research has revealed that from infancy through adulthood, whether referring to a person, or a state's population, or all Americans, health is heavily impacted by another category: socioeconomic factors.

Recently, the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) linked SDOH to population health, noting SDOH as a key to population health.

"Social determinants at the population level are considered underlying, upstream, or more fundamental determinants of health and disease and are amenable to change through public policy," the report noted.

With experts acknowledging that social risk assessment may impact healthcare costs, social risk measurement may also impact reimbursement rules. The trend away from fee-for-service models to the recent focus on pay-for-performance may even meet up an alternative payment model influenced by managing the impact of a patient's specific SDOH challenges.

How Are SDOH Measured?

Several recent publications report social risk assessment as an approach to further investigate SDOH impact on health and healthcare costs. In a November 2017 academic study published in Population Health Management, the authors note: "Given the small number of existing measures in the clinical context assessing social determinants, measure development for risk assessments should be considered a higher priority…"

One specific social risk assessment measurement tool is described by the National Academy of Medicine, a tool that is currently part of a Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) Innovation grant. In a January 2016 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) Perspective, CMS officials discussed how social risk assessment will help "support a transition from a health delivery system to a true health system."

CMS Innovation Grant: Accountable Health

Communities Model and Social Risk

Assessment

Several rural

organizations (Tifton, Georgia, and Leland,

Mississippi) are part of a five-year CMS

Innovation Center grant exploring how social risk

assessment might "reduce avoidable health

care utilization, impact the cost of health care, and

improve health and quality of care for Medicare and

Medicaid beneficiaries," according to the

agency's April 2017

press release. The grant

is using the Accountable Health Communities Model (AHC)

which:

- Is "…based on emerging evidence that addressing health-related social needs through enhanced clinical-community linkages can improve health outcomes and reduce costs…"

- "…addresses a critical gap between clinical care and community services in the current health care delivery system…"

- Will test "…whether systematically identifying and addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries' through screening, referral, and community navigation services will impact health care costs and reduce health care utilization…"

- Uses a standardized screening tool, "Core Health-Related Social Needs Screening Questions" to assess health-related social needs. The tool helps uncover gaps "between clinical care and community services in the current health care delivery system" and includes questions like "What is your housing situation today?" and "In the past 12 months has the electric, gas, oil, or water company threatened to shut off services in your home?" Interpersonal safety is also assessed with questions such as "How often does anyone, including family, threaten you with harm?"

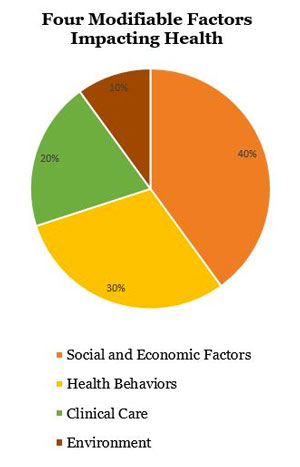

The grant model also includes attention to the four modifiable factors impacting health: physical environment, 10%; clinical care, 20%; health behaviors, 30%; and social and economic factors, 40%.

New Measures: New Rural Leadership Needs

Rural organizations are taking a step back for a broader look at the four modifiable factors impacting health outcomes. Though clinical care is only one factor, health care leaders recognize that patients, payers, and communities are looking to them — the healthcare delivery organizations — to lead needed efforts coordinating all four factors. Several rural healthcare organizations have already answered the leadership call by implementing social risk assessments into routine patient care.

Understanding the social needs of patients is not new to clinical teams and their organizations. These care teams recognize that their daily work is centered on getting patients healthy. They also recognize that keeping patients healthy after a hospital discharge or completing a series of clinic visits sometimes feels outside their control: They know patients who return to the same social determinants of health that triggered the initial illness will often be readmitted and require another series of clinic visits.

Though acknowledging that clinical care only contributes 20% to overall health outcomes, clinical teams and their healthcare organizations now recognize it's their time to help formally evaluate the impact of SDOH: they must be vested in not just providing clinical care, in not just working with patients to modify unhealthy behaviors, but in working with other organizations associated with the socioeconomic and environmental factors that influence their patients' health.

Georgia Organization Takes On Social Risk Assessment

Tift Regional Health System in rural Tifton, Georgia, is one such leader wanting to transform itself to that "true health system" described by the NEJM authors. Valerie Levy, the Tift Regional Medical Center Accountable Health Communities Grant Program Manager, said her organization already had successes with healthcare delivery models such as becoming an Accountable Care Organization and using a Patient Centered Medical Home model. They were ready to move on to the next challenge. Assessing social risks of their clinic and hospital patients, exploring their patients' social determinants of health has moved from the "to do" to the "active project" list as a CMS grantee.

"Our organization is very proactive and is at the forefront of healthcare," Levy said. "But we knew we needed to focus at a more elemental level to look at social determinants of health. We believe that addressing these social needs will help us impact health outcomes."

Levy pointed out that Tift is using their grant award to implement a formal social needs assessment that is streamlined and sustainable. Helping with each department's implementation activities, she shared how energized she is by her coworkers, hospital leadership, and especially the Tifton community.

"They have taken to heart the vision of our executive leadership," Levy said. "Because these teams live in this community, they know what's happening because of these unmet social determinant needs. Our staff wants to be part of what changes their patients' health for the better now, and what will sustain it for the future."

Solving Unmet Social Needs: NC-REACH's Best Practice Model

In Dunn, North Carolina, CommWell Health is an organization familiar with the activities described as part of the CMS's grant model: assessing unmet social needs, providing navigation assistance, and creating an inventory of community service organizations. These steps were required for their participation in a Health Resources & Services Administration's (HRSA) HIV/AIDS Bureau's national initiative, a federal demonstration project part of the Bureau's Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS).

CommWell, the only rural member of the 9 demonstration sites, now serves as a Best Practice Model. They've received numerous awards and recognition for their program NC-Rurally Engaging and Assisting Clients who are HIV positive and Homeless, NC-REACH.

Lisa McKeithan, NC-REACH and Positive Life program director, said their team completed social determinant risk assessment steps similar to those being used in the AHC model, for example screening for housing needs. CommWell's leadership — almost from the ground up — built relationships with community service organizations in order to meet housing challenges like those associated with "hidden homelessness," an unstable housing issue where a client might go from a family member's couch, to a friend's couch, to a stranger's couch without having stable housing. That collaborative activity with other organizations became a community solution, the Community Housing Coalition, now part of CommWell's Best Practice Model.

"When we created the Community Housing Coalition, our strategy was simply to identify and connect with all the community resources in our local communities," McKeithan says. "So we invited the local homeless shelter organization, the United Way, the Salvation Army, Veterans Affairs, the faith-based community, and more. We invited everybody, because we wanted everybody. We wanted everybody in the same room and we wanted everybody to have a voice."

Making sure the community has a voice is where a community's healthcare organization can lead the necessary community work around the social determinants of health. The health expert leadership becomes an organizing voice for the community. Having a large number of non-medical individuals in a room, most strangers to each other, giving each a voice, and having a strategic objective to accomplish in a limited amount of time might create a challenge for the hosting healthcare team. But McKeithan said, not so much for them. Why? She believes that CommWell's dedication to leadership and development (L&D) for every one of their employees is a major factor in NC-REACH's success, starting with McKeithan and her colleagues feeling well-prepared to run a meeting of that magnitude.

Andrea Morales, CommWell's Communications and Marketing Manager, further explained CommWell's L&D program, the Eagle Excellence Program. Created by CommWell's CEO, Pam Tripp, the course begins with a two-year on-line curriculum, called Eagle Excellence Flight School. The Flight School is available to all CommWell employees and covers the foundations of leadership and "includes topics such as public speaking, team building, conducting and facilitating successful meetings, quality improvement, and Health Center operations." Following Flight School graduation, an employee becomes an in-person educator for other employees, applying what they've learned to other settings, such as quarterly staff training meetings.

"The goal of our program is that everyone is empowered to have a voice," Morales said. "It's a program that builds confidence, self-esteem, self-awareness. Our CEO believes when our employees develop these special skill sets, like those required for conducting a large meeting geared to community collaboration, they create an empowered organization that can accomplish anything. A great example is the accomplishments of our NC-REACH program."

McKeithan believes this type of training, spread throughout the organization, keeps the CommWell team always ready for the "What's next?" challenge.

Our motto is 'we want our excellence of tomorrow to be better than our excellence of today.

"Our motto is 'we want our excellence of tomorrow to be better than our excellence of today," she said.