May 17, 2017

Feasting on Rural America: The Spread of Tick-Borne Diseases

by Jenn Lukens

Part parasite and part predator, the tick has become one of the nation's most harmful bugs. Overgrown, humid areas are prime real estate for these critters, making rural America more susceptible to their growing numbers and the diseases they carry.

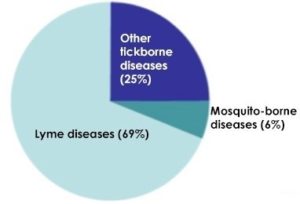

Even with the paranoia they incite, ticks have managed to lie low, out of the spotlight. Not until recently has the national conversation started picking up speed as Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses have become the most prolific zoonotic diseases in our nation. Lyme disease, the most-reported of the 20+ tick-borne diseases in the United States, is estimated to infect around 300,000 people every year.

Thankfully, out of the 90 tick species found in the U.S., only a handful are known to transmit bacteria harmful to humans. But the microscopic pathogens that have evolved with the growing tick population can cause a myriad of health issues including neurological disorders, heart problems, extreme fatigue, depression, and even death, to name a few.

Many individuals and groups are working to eradicate these diseases, or at least decrease their incidence. Scientists are developing vaccines. Medical researchers are studying alternative diagnostic and treatment methods. Organizations are actively promoting policy changes and increased funding. Each effort is one step closer to blocking the rapid spread of tick-borne diseases across the nation.

Time is of the Essence: A Case of Lyme

Nancy Lankow isn't sure how she missed it. She and her husband habitually do tick checks before bed, but she didn't notice the blacklegged tick attached to her upper arm. She suspects picking it up in the flowerbed or woods outside her country home near Hackensack, Minnesota. It took some effort getting it out. "It was well dug-in. As you can see from the picture, it looked like it was headed to the other side of the earth," said Lankow.

She sent the photo and a note to her primary care physician at the Essentia Health St. Joseph's-Brainerd Clinic, a rural facility about 60 miles from her home. By the time the clinic called back, a bull's-eye rash had spread on her arm. Lankow recalled, "They said, 'Can you be here by four o'clock?' I decided, at that time, there was no question that it was Lyme."

Lankow's case was classic. Her bull's-eye rash is the most recognizable symptom of Lyme disease, but it doesn't appear in every case. The corkscrew-like bacteria that causes Lyme can drill into any part of the body, invoking a constantly changing set of symptoms.

With one look at the infected area, Lankow's doctor prescribed several weeks of antibiotics – the recommended treatment for most tick-borne diseases – and commended her for being proactive. Waiting even a few weeks could have put her at greater risk for a prolonged battle with Lyme disease. For rural residents like Lankow, the ability to see a local medical provider and begin treatment within days of showing symptoms is critical.

Home Sweet Home: The Rural Attraction

In general, rural residents are more susceptible to tick-borne illnesses because of their proximity to preferred tick habitats, whether through their occupation or recreational activity of choice. Rural landscapes offer an ideal environment for disease-producing bacteria and their zoological hosts.

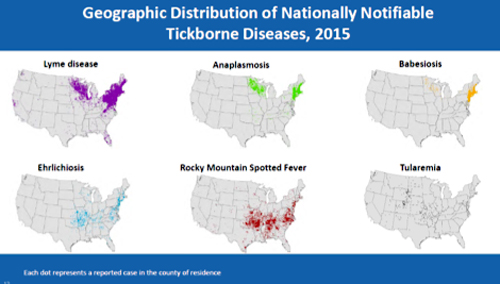

Growing up in a rural area, Lankow was used to ticks, "but now Lyme disease has upped the ante," she stated. Minnesota is ranked in the top seven states with the most reported cases of Lyme, an indication that the disease, which started in the Northeast, is on the move. Reforestation, increased travel, changing weather patterns, and changes in ecosystems and small mammal communities are just some factors contributing to the increase and migration of tick-borne illnesses.

The number of reported tick-borne disease cases has increased over the past two decades. At least a quarter of all new Lyme cases occur in children ages 5-14, affecting their ability to learn, socialize, and even get out of bed. Experts agree that their susceptibility is largely due to lifestyle, as children tend to spend more time outdoors than other age groups.

Although Lyme is the most common tick-borne disease in the U.S., numerous others exist and new ones are being discovered. Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, Powassan virus, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), and Tularemia are just a few. Diseases tend to claim different parts of the country, incite different symptoms, and are transmitted from different tick species.

A Tick's Host of Choice: The White-Footed Mouse

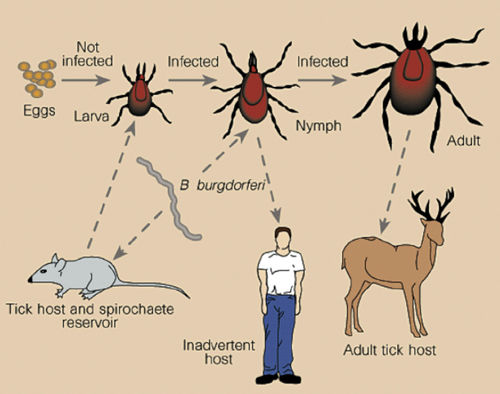

Dr. Maria Gomes-Solecki is a doctor of veterinary medicine studying the development of oral vaccine delivery vehicles at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. One of her accomplishments has been the invention of a vaccine that prevents the spread of Lyme disease in white-footed mice, a common host, thereby reducing the number of ticks carrying the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium.

Her vaccine was tested via pellets put in live traps and strategically placed throughout a few sites the size of football fields in southeast New York. Mice that ate the pellets received a boost in antibodies, killing the B. burgdorferi bacterium inside their bodies. The results of the 5-year study showed a 76% reduction of the pathogen in nymphal ticks (the kind that transmits the bacterium to humans). Her field study, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute of Health (NIH), provides a method for inducing "protective immunity" from tick-borne diseases through animals.

"If you just target mice and are able to reduce the number of infected ticks, it should be a huge impact in the number of people infected later down the line," said Gomes-Solecki. Currently, the vaccine is circulating through United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) licensure process for commercialization approval. Gomes-Solecki and her team have rural areas in mind for upcoming pellet distribution.

"In a completely rural area, you would have to think about distribution from planes or something on more of a mass scale," commented Gomes-Solecki. "In state and local parks, the park departments often know where the populations of animals are and know where to put the boxes that would contain the vaccines."

The vaccine is one of several efforts of its kind to decrease tick-borne diseases through ecological methods. This One Health approach, or "the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines – working locally, nationally, and globally – to achieve the best health for people, animals, and our environment," is what CDC, USDA, and zoonotic experts are looking to as the solution for managing and reducing the spread of diseases like Lyme. Her work to develop a human vaccine is on hold for now, waiting for more funding in order to continue.

Don't Let It Go to Your Head

Dr. Robert Bransfield, clinical associate professor at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and former president of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Educational Foundation (ILADEF), sees patients with tick-borne diseases at his private practice in Red Bank, New Jersey.

Bransfield speaks from experience: "When there is a failure in the healthcare system, people are sent to psychiatrists." His patients come from all over the country, even flying in from rural areas where psychiatrists are few and far between. Loggers, farmers, Amish, and Mennonites – most arrive after the cognitive problems have already set in.

By the time they get to him, "They are sick, and they feel lost. Insurance companies are turning their backs on them, families don't understand it, employers don't understand it, and they don't understand it. They feel upset and need to know how to deal with something that we call an 'invisible disability.'"

In many cases, the brain is one of the last places the bacteria hits, so many of Bransfield's patients have had ongoing symptoms for years. "I see depression, people who are suicidal. Sometimes they can get violent." According to Bransfield's research, as many as 1,200 suicides every year in America are related to Lyme disease. Those with mental symptoms from Lyme are in the hundreds of thousands.

They are sick, and they feel lost. Insurance companies are turning their backs on them, families don't understand it, employers don't understand it, and they don't understand it. They feel upset and need to know how to deal with something that we call an 'invisible disability.'

In his article Lyme Disease and Cognitive Impairments [no longer available online], Bransfield explains that the cognitive symptoms of Lyme disease include difficulty sustaining attention, memory, processing information, slurred speech, reading comprehension, and organization/planning. Bransfield recalls seeing these symptoms in patients at his practice in the Great Dismal Swamp region on the border of Virginia and North Carolina before Lyme disease was a known illness. Conversations would include delayed responses and grasping for words. "It was the oddest thing. People at the clinic didn't understand it," he recalled. It wasn't until after Lyme disease was discovered in the early 1980s, that Bransfield made the connection.

Because of the complexity of tick-borne diseases, Bransfield uses a multi-level approach to finding a solution. He starts by treating the symptoms. "Whether depression, anxiety, or insomnia…I methodically attack each of those [symptoms] and try to improve them. That can often break the cycle of disease progression," he said. Sometimes this includes prescribing antibiotics, and other times, it's with things like a CPAP machine for better sleep.

Local Change through a National Nonprofit

Since the 1990s, Pat Smith and her national nonprofit, the Lyme Disease Association, Inc. (LDA) [LDA ceased operations 12/5/2024], have been encouraging the passage of a bill allowing a work group to advise the government in Lyme disease solutions and research priorities. Earlier this year, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act, which addresses the needs of many diseases and includes the formation of a tick-borne diseases working group.

Lyme patients, advocates, treating physicians, and researchers will join the work group set to start by the end of 2017. "We will have representation at the table from those who have been most affected by the disease," said Smith. "This will be a huge game changer that would influence public policy and, we hope, funding."

Smith was on her New Jersey district's board of education when Lyme broke out in the 1980s. She got involved with a state-wide Lyme organization out of concern and because of her own experience with the disease: two of her daughters contracted Lyme, one missing school for years as a result. Smith became president of the group and helped develop it into LDA. Run by volunteers, the organization's mission extends well beyond its policy work — it also funds research and education efforts, as well as paying for diagnoses and treatment for uninsured children who have Lyme disease. LDA also serves as the lead organization for LDAnet, a network of 45 independent tick-borne illness groups across the country.

LDA often awards educational grants to its partners, many of whom are working to improve the situation for rural areas: events like the one Midcoast Lyme Education and Support recently put on in Maine's rural midcoast region draws people from every part of the state. LDA's educational materials are distributed regularly to public health offices, the military, individuals, schools, and partner groups like the Lyme Association of Greater Kansas City that supplies school nurses in rural districts with LDA resources.

Educating Doctors

I was stunned to realize how much I didn't know that was already knowable. My conception of Lyme – a bit of a rash, maybe some achy joints, then you get an antibiotic and everything goes away – was inaccurate.

While practicing in rural Howland and Lincoln, Maine, Dr. Beatrice Szantyr, an internist/pediatrician now retired from clinical work, took a closer look at the disease to help a patient. "I was stunned to realize how much I didn't know that was already knowable. My conception of Lyme – a bit of a rash, maybe some achy joints, then you get an antibiotic and everything goes away – was inaccurate," she recalled.

She attributes the lack of clarity among the medical community to the emphasis on certain objective aspects of the disease when it was first uncovered. "In retrospect, that likely suppressed some of the early information that was really important to have," said Szantyr. Additionally, the lack of highly sensitive and reproducible tests, the persistence of illness in some patients despite treatment with antibiotics thought to be effective, and the still incomplete science of this infection have resulted in conflicting views about Lyme disease.

The debate is ongoing in the medical field and government groups specifically regarding its definition, diagnosis, and treatment.

Szantyr has spent thousands of hours exploring and educating medical and public audiences on tick-borne diseases. As a member of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), medical advisor to MaineLyme, and member of Maine's Vector Borne Disease Work Group, she has helped to bring tick-borne illnesses to the forefront of medical and public health conversations in her state.

When advising clinicians regarding diagnosing a tick-borne disease, Szantyr said, "You cannot abdicate your clinical judgment. No laboratory test is ever going to be better than putting together all the data that you have and making a clinical assessment." She also recommends providers have a working knowledge of local tick-borne diseases and not dismissing symptoms just because there are no known local cases of the disease. As people and animals travel, so do ticks, widening the spread of their growing population. Doctors can boost their knowledge and get continuing medical education (CME) credits through courses like Dr. Elizabeth Maloney's Partnership for Tick-borne Diseases Education.

Dr. Beatrice Szantyr's tips for preventing tick-borne illnesses:

- Keep your grass cut short and create a 3-foot or greater mulch, woodchip, or stone border between your lawn and abutting woods to further separate home and tick environments.

- When around a tick-infested area, wear light-colored clothes for better detection.

- Tuck your clothes (shirt into pants, pants into socks) to create a barrier between your skin and ticks.

- Wear insect repellent with a DEET concentration >23%. Spray it on your skin to get the best results (the reaction between the spray's chemicals and your body's oils/heat creates a vapor layer that repels insects).

- After being outside, perform a tick check on yourself and children, especially places that restrict motion: groin, waist, belly button, bra line, behind knee and ears, and scalp. Ticks can be as small as poppy seeds.

- If a tick has attached to your skin, don't panic. Remove it promptly and carefully. Tweezers or "tick-scoops" have proven to be the best for a clean removal. Pull the tick away from your skin with gentle, constant pressure. Clean the wound site. Put the tick in a bag and bring it to your healthcare facility if symptoms ensue or to pursue preventive treatment.

- Treat a set of clothing with permethrin, a tick and mosquito-killing agent that has been proven to reduce the amount of tick bites on one's body. You can also purchase clothing that has already been treated.

- To kill ticks on clothing, place clothes in the dryer and run on high heat setting for 6 minutes.

Prevention and Early Detection

When caught early, antibiotics have been shown to be effective treatment for Lyme and other tick-borne disease. Follow up is important. In Lankow's case, the rash went away and no other symptoms set in after her three-week antibiotic cycle. The experience has made her a strong believer in prevention and early detection. "Keep watching and respond quickly. Don't wait. My daughter learned that the hard way."

Keep watching and respond quickly. Don't wait. My daughter learned that the hard way.

Lankow's daughter was diagnosed with Lyme after several weeks of escalating symptoms, which became debilitating. Several other family members have also had the disease, including her husband. But, like so many rural residents, that hasn't stopped them from enjoying the great outdoors, gardening, and cutting and splitting firewood. "I don't think it's going to make a big change in what we do. We'll be very careful on tick checks and perhaps more assiduous with tick spray," said Lankow.

Additional Resources

- CDC's Press Kit: Lyme and other tickborne diseases – outlines risks and protection tips.

- ILADS Doctor Search – Suggests Lyme doctors in a patient's area.

- Insect Repellent Search Tool – EPA resource gives a detailed overview of repellent varieties.

- Lyme Disease Checklist – can create a likely diagnostic report based on a patient's symptoms. To be shared with medical providers.

- Tick ID Chart – can help identify tick species specific to U.S. regions.