Jul 12, 2017

“Doing Something Exceptional”: Rural Communities and Colorectal Cancer Screening

It chips away at quality of life. It shaves years off a lifetime. It's the second leading cause of death from cancers affecting both men and women. And despite its unique status as a preventable cancer, the National Cancer Institute's 2013 report revealed the nation's colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rate is only 60%, lagging way behind cervical and breast cancer with screening rates of 73% and 80%, respectively.

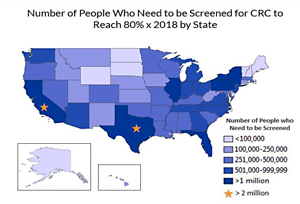

The American Cancer Society's map of states' CRC screening rates provides a quick visual of rural screening disparities, the mostly-rural states prominent in darker green. According to Healthy People 2020 (HP2020), only 58% of nonmetropolitan residents were screened in 2015, compared to 63% of metropolitan residents (data no longer available online). For people never screened, a 2013 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report shows a similar rural disparity. Rural disparity is also demonstrated by a recent Arizona study. According to Arizona's state cancer registry, rural residents presented with more advanced CRC disease, thought largely due to inadequate screening. And a July 7 CDC MMWR Rural Health Series report delivering focused details on rural-urban cancer incidence and death rates said that "disparities could be attributed to differences in adherence to screening guidelines."

Dr. Van Breeding, Director of Clinical Services at Mountain Comprehensive Health Corporation in rural Whitesburg, Kentucky, said he thought that, as much as their patients allowed, their clinic did a good job providing preventive care, including CRC screening. But, their 2012 baseline data for that quality measure came as a surprise.

When I found out we were only 19%, I said, 'That's horrible! We've got to do better than that!'

"When I found out we were only 19%, I said, 'That's horrible! We've got to do better than that!'" Breeding said.

In Idaho, Heather Hodges, Director of Quality Improvement at Clearwater Valley Hospital and Clinics in Orofino and St. Mary's Hospital and Clinics in Cottonwood, said they also found their CRC screening rates were hovering around 50%, less than the HP2020's goal of 70%.

"Once you've seen your baseline," Hodges said, "you're motivated to get where you need to go."

Where CRC Screening Starts: Talk. Talk. Talk.

A recent American Cancer Society survey showed that "nearly all unscreened people knew they should be screened." Many who hadn't completed screening assumed if they had no family history, they were at no risk for the disease. Others perceived the test was expensive, complicated, painful, embarrassing, and only needed for worrisome symptoms. With information like this, many providers feel that talking about CRC screening seems not only delicate, but time-intensive in order to dispel myths about screening, especially when discussions around other cancer screenings are often as simple as "It's time for you to make an appointment for a pap smear/mammogram/ prostate check."

So, talking about colon cancer screening includes a lot of talk. There's the talk about home testing of feces versus a colonoscopy. If interest is in the latter, there's more talk. Talk about seeing another provider who does the test, followed by talk about getting the prescription for the colon purge medication. And more talk about why the colon lining needs to be "clean" so the fiber-optic hose traversing the private area of the body can see small abnormalities. If a patient is interested in the home feces test instead, there's even more talk about the how-to's on feces collection and the need for yearly checks. So, for providers and patients alike, CRC screening involves talk, talk, and more talk.

But Whiteburg's Breeding insists it doesn't take that much time — and that "talk" was exactly the key to launching their Appalachian community's CRC screening success. He said their effort started with everyone in their clinic talking about it: from check-in personnel to lab team members to providers — everyone started talking about colorectal cancer screening.

We got everyone who had contact with the patient to talk about it, starting with a simple question: 'Have you ever been screened for colon cancer?'

"We got everyone who had contact with the patient to talk about it, starting with a simple question: 'Have you ever been screened for colon cancer?'" Breeding said.

Clearwater Valley's Hodges said they used a similar approach, talking with everyone eligible for screening. Using an electronic record indicator, providers were reminded to talk to unscreened patients during any appointment scheduled for any reason. In addition to talk, they mailed reminders to patients.

"We're renegades out here and we wanted to do things our way," Hodges said. "I did some research on primary care strategies and methods geared to increasing colon cancer screening, and we decided one of the first places to start was at 'point of care.' No matter why patients were at the clinic, if we'd see those patients needing screening, it was an opportunity, and we'd talk about it."

Why Screen? Simple Answers

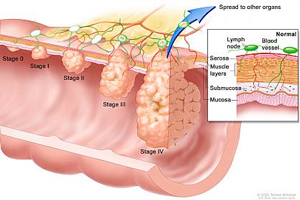

According to the CDC, with current screening rates, there are still over 135,000 new cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed yearly, along with over 50,000 deaths. And if diagnosed at a stage where it is metastatic, spreading outside the lining of the colon and invading the liver, lungs, and bones, 5-year mortality data shows that survival rates are only 5 to 13%. Screening can improve all these numbers.

In addition, data surrounding costs and disability help make the case for screening campaigns. Aside from the associated with the emotional and physical aspects of having colorectal cancer, research also demonstrates that for the elderly, it is one of the most expensive cancers to treat, with projected costs of $17.7 billion by 2020. And a study published in the 2015 Journal of the National Cancer Institute concluded that, compared to patients with breast and prostate cancer, colorectal cancer patients had higher "excess medical expenditures" and "excess employment disability."

Despite the benefits of screening, Hodges and Breeding said they still met some organizational challenges to their screening programs. Both shared that their most powerful tool in overcoming these challenges was a simple statement: "But, colon cancer screening is the right thing to do."

Rural CRC Screening: Who Are We Screening? When Are We Screening?

Current 2016 screening guidelines are provided by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and apply to rural and urban populations alike. No one is considered "low-risk," so recommendations start with those of "average risk." For people without personal or family history of colorectal cancer, screening should start at age 50 and continue until age 75, the frequency depending on the screening test chosen. For those aged 76-85, the screening decision should embrace a patient's overall health status, noting that there may be some benefit for those never screened. If a family history of colon cancer is present, screening starts earlier, aligned with the age the family member's cancer was diagnosed. Still other recommendations exist for those with inflammatory bowel disease, like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis.

But, for Breeding in Appalachia, "risk" had a different meaning. After first learning about his clinic's baseline screening rates, he began to think about growing up in Whitesburg, getting his entire education in Kentucky – he'd even been a patient at the very clinic he now serves in this Appalachian region. He suddenly realized that his family, his friends, his community, all were living in an area that colorectal cancer seemed to own, an area where its incidence and death rates are the highest in the country. Added to this was the discovery that, during his own screening, a precancerous polyp was detected.

"With no risk factors other than living here, my own results really made me an advocate to make it easier for patients to get screening done," Breeding said. "And we needed to make people realize how important it is to have this done. You might not have any history but, by waiting, you might end up having colon cancer."

CRC Screening Importance: Prevention and Early Detection

CRC screening uses two strategies: a head start approach, and the yearly hunt approach.

Most colorectal cancers start with a bud-like structure in the lining of the large intestine called a "polyp." Over a 10-year period of time, a polyp can turn into cancer. A procedure called a colonoscopy uses a lighted tube to not only see a small polyp, but remove it, getting a 10-year head start on preventing colon cancer.

When colonoscopy is not an option, either by choice or by circumstance, a yearly hunt for intestinal blood is used for screening. Since a pre-cancerous polyp or full-blown colorectal cancer has blood vessels that become damaged and bleed as feces pass by, intestinal blood sticks to the stool and can be detected by special tests. But, because polyps and cancers don't always bleed, this test must be done yearly in order to stay on top of any previously non-bleeding polyp, or to detect an existing cancer before it spreads outside of the colon.

Here's a video tour through an inflatable colon:

Rural CRC Screening: CDC Speaks Out

Dr. Djenaba Joseph, medical director for the CDC's Colorectal Cancer Control Program, said rural geography causes challenges in meeting recommended screening rates.

"Screening rates are lower in rural areas, where geography causes barriers like lack of access to providers and lack of specialists or access to those specialists," Joseph said. "In some states, there are hundreds of miles between the patient and the nearest endoscopist. But, regardless of location, I tell everyone, rural and urban, you can improve rates by knowing your population. Know the number of endoscopists in your area, know the population you are trying to reach, know the income limits, and know insurance status."

She emphasized that knowledge about available resources helps providers and patients decide on the best CRC screening test. Joseph also pointed out that evidence-based interventions such as reminders work well in rural areas and can help small communities improve screening rates. For patients, who often are dealing with acute health problems or multiple chronic problems, reminders are useful tools. For providers with multiple high-priority tasks during an office visit, chart reminders may prompt a short conversation about screening needs.

But, regardless of location, I tell everyone, rural and urban, you can improve rates by knowing your population.

"And there's lots of resources out there," Joseph said. "No one needs to create anything from scratch. Our [CDC] information, or the American Cancer Society, or the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable all have multiple free resources that can be narrowed down in order to find ideas on helping small, rural practices improve screening rates in their clinics."

In the recently released CDC report, cancer screening programs that focused on a population approach were further emphasized: "The goal is to work with health care systems, health care payers, health care purchasers, and other partners to implement interventions that address barriers such as providing transportation assistance, having clinics with modified hours, and providing assessment and feedback reports on clinical practice performance. Communities with lower screening rates or higher incidence of and mortality from cancer might particularly benefit from these interventions."

Resources

Many resources are available for organizing CRC

screening efforts in advance of Colorectal Cancer

Screening Month, March 2018:

- American Cancer Society: Colorectal Cancer

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Screen for Life: National Colorectal Cancer Action Campaign

- Community Preventive Services Task Force: The Community Guide — Increasing Cancer Screening: Multicomponent Interventions

- The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable: 2019 Colorectal Cancer Screening Messaging Guidebook: Recommended Messaging to Reach the Unscreened

Rural Idaho Clinics: Success with FIT Testing

Idaho's Orofino and Cottonwood teams began their CRC project as part of their holding organization's push for quality improvement. After researching options and methods, they decided on a three-pronged approach: get baseline data, use mailed and electronic reminders, and take advantage of "health touch" moments, whether talking with a patient during an office visit or reaching patients at public health-oriented events.

Hodges said the subject of CRC screening is a bit distasteful, but this can't prevent healthcare organizations from doing community outreach. For example, she and a medical provider even presented at a lunchtime Rotary meeting where, despite the topic, they were welcomed.

Proving how rural organizations can align with Dr. Joseph's recommendations, Hodges said her organization understood that, even though their community had colonoscopy providers available (family medicine physicians and gastroenterologists), for many patients, their payer coverage for this procedure was lacking. So instead of a colonoscopy, screening efforts also included FIT testing, or fecal-immunochemical test: the test that tracks intestinal blood shed from pre-cancerous polyps and existing colon cancer.

"At first, our providers doubted the FIT results because, in one calendar year of 250 tests, 123 were positive," Hodges said, "but, when the follow-up colonoscopies showed that around 30 were abnormal, but not cancer; and another 49 had precancerous pathology and 1 had invasive cancer, they realized that the test was saving lives."

Hodges shared that one key to improving rates was sheer competition using data transparency. In their clinic setting, a flat screen TV with rotating information showed screening rates accomplished by individual providers/teams.

"I'd always heard this worked, this internal competition," she said, "and it did."

Hodges learned that, in addition to patient education, the staff also needs education around the basics of colon cancer screening.

"It's two different conversations," she noted. "Staff education is different from educating patients. Staff education needs to be around documentation, how to have conversations about screening, how to screen, why to screen, and using staff education guidelines are important."

According to Hodges, their clinic went from 52% to 69% to now setting a goal of 75% for 2017, well on target for meeting the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable's goal of 80% by 2018, despite having patients in the denominator who will always choose not to be screened.

Hodges also emphasized that their clinics' screening process was a heavy lift for everyone. But, when she reminds staff that what they've done added the equivalent of more than 18,000 sunsets to the lives of those in their community, everyone realizes the effort is worthwhile.

High-Risk Rural Kentucky: CRC Screening Means Community Screening

Breeding said it was one thing to be surprised by their clinic's CRC screening rate of less than 20%, but surprise became concern when their clinic's quality director came to him with the news they'd been contacted by an outside agency wanting to help improve rates.

I suddenly felt ashamed, ashamed to think someone from the outside was going to have to come here, tell me how to be a good physician, a good steward for my community.

"I suddenly felt ashamed," Breeding said, "ashamed to think someone from the outside was going to have to come here, tell me how to be a good physician, a good steward for my community. I knew I had to do something immediately. We couldn't wait."

Before the outside agency had a chance to gear up, Breeding launched a grassroots effort, starting first by engaging their clinic's quality committee members. Breeding said the momentum for colon cancer screening built fast. A focus team emerged, spreading the effort to every clinic staff member and all providers. Soon, everyone was talking about CRC screening.

"Patients started hearing about it, over and over again," he said, "and it just wasn't something they wanted to worry about. But, after what happened with my screening, it made it easier for patients to understand."

Again, as the CDC's Joseph suggested, success came from knowing the population. Breeding said they talked to their area insurance carriers about ensuring colonoscopy coverage. They also discovered that patients without insurance could get assistance from the health department due to the area's high risk. Next, the local hospital decided to improve the endoscopy area, and the area's surgeons, who performed the colonoscopies, immediately accommodated a structured approach to direct screening. Mondays and Fridays became designated testing days to accommodate prep and recovery times.

According to Breeding, many factors drove their screening rates from 19% to 73% by May of 2017, but one of the most powerful was a new dynamic that emerged in their tight-knit community: when community members looked into the face of a family member, a friend, a neighbor, and realized that person was living in an area of high colorectal cancer incidence and death rates, they encouraged one another to get screened. With this effort, Breeding shared that more than 30 lives have been saved. Their new screening goal — their community's goal? It's now 100%.

Among the many lessons learned in this effort was patients' understanding that the clinic was not just a place to come when sick, but a place to come to get, and stay healthy. According to Breeding, the clinic is now leveraging those methods that worked to improve CRC screening to improve all cancer screening, immunization rates, and hypertension and diabetes control.

We learned, while working to make colon cancer a core topic, that we were able to do dramatic things, exceptional things.

"We learned, while working to make colon cancer a core topic, that we were able to do dramatic things, exceptional things," Breeding said. "We went way above what anyone predicted we could do. This was an exceptional accomplishment not by me, not by our staff, not by our clinic, but by our whole community. And that's what it takes to accomplish a feat like this. It takes exceptional dedication, perseverance, and hard work by the whole community."