Sep 20, 2023

“This Is Not My Grandmother's Summer”: Mitigating the Health Impacts of Extreme Heat in Rural Communities

Kathie Cox admits she should have known better. As a public health educator and designated "heat illness prevention specialist" for Scotland County, North Carolina, she has given countless community presentations and coordinated numerous outreach campaigns on heat safety and heat-related illness. And yet: "I kind of got hard-headed one day," said Cox.

It was early May, upper 80s with a light breeze. After work, Cox attended an exercise class, then took her dog out for a two-mile walk. In a column published in her local newspaper, The Laurinburg Exchange, Cox recalled what happened next:

"Because my neighbors on either side of me had just mowed their lawns, mine looked like a field of unsightly, embarrassing, knee-deep weeds you could hide a Great Dane in. Not to be outdone, and already hot and sweaty, I decided to mow at least my front yard, which turned into the entire yard. Not only did I not stop to take breaks — (Lord, help me if I had to pull the starter on the push mower again), I had not eaten much during the day, nor did I stop to drink water or cool off — even though I knew I should!"

Soon, Cox was experiencing symptoms that she recognized from her own presentations and educational materials: weakness, lightheadedness, headache, nausea. She went inside to cool off and rest; but after two hours of worsening symptoms, she called her daughter for help. "Because I was being hard-headed — saying, 'I know I can do this, I can knock this out' — I suffered for it, I paid dearly," said Cox. "And thank goodness it didn't get any worse to where I had a heat stroke."

Though Cox was eventually able to recover without a trip to the local hospital, many of her neighbors in the rural Sandhills region of North Carolina are less fortunate. Research in North Carolina has identified the Sandhills region as having some of the highest rates of heat-related emergency department (ED) visits in the state.

"We know that children, older adults, pregnant women, those without access to air conditioning at home or at work, outdoor workers, athletes, and those with chronic health conditions are disproportionately impacted by heat," said Sarah Hatcher, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) Climate and Health Program Lead. "Compared to urban areas, rural areas have higher proportions of people who belong to some of these groups."

Since 2018, the NCDHHS has been working closely with community partners — including Cox — in four rural Sandhills counties to educate at-risk populations about the health impacts of extreme heat and alert the public when temperatures climb dangerously high. A veteran health educator, Cox saw the opportunity in her personal brush with heat-related illness. "This was all so embarrassing," said Cox. "But nevertheless, I wrote that article to let people know that this can happen to anyone — even people who are informed."

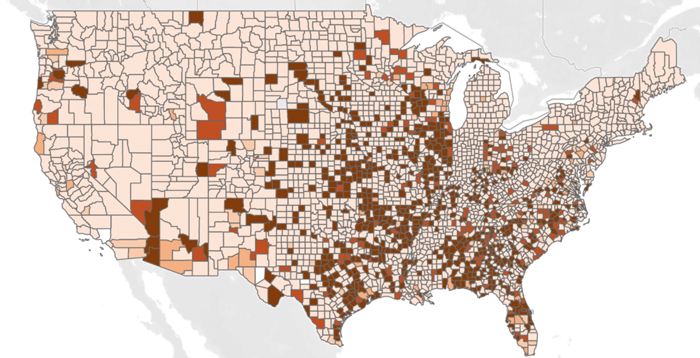

Rural susceptibility to heat-related illness and death is not limited to North Carolina or even the Sun Belt; states as far north as Minnesota and Wisconsin have noted similar trends. In April 2022, the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published an analysis of nationwide data on heat-related ED visits between 2016 and 2020 [no longer available online]; an AHRQ statement summarizing the report noted: "Rural counties were more likely to have higher rates of ED visits related to heat exposure — a finding that challenges assumptions that health problems related to extreme heat are most acute in urban areas."

The health impacts of extreme heat events are being felt by both urban and rural populations. But experts say the factors contributing to urban and rural susceptibility may differ significantly — and some of the most promising strategies for mitigating the impacts in urban areas may not be as useful in sparsely populated rural counties.

A cooling center that's 30 miles away doesn't really do you any good.

"A cooling center that's 30 miles away doesn't really do you any good," said Ashley Ward, Director of Duke University's Heat Policy Innovation Hub. "There is a perfect storm of ingredients that make rural heat risk something that is not only important for us to think about, talk about, and understand better — but also very difficult to mitigate. And so we need to come up with some really innovative solutions that are appropriate in the rural context."

Assessing Risk — and Leveraging Social Infrastructure

Assessing the risk of heat-related illness and death is "not just about maximum temperatures," noted Ward, who has studied the health impacts of climate extremes for over a decade. A dizzying array of factors beyond the local daily high also impact individual and population-level risks — including age, occupational exposure, local labor laws, housing quality, access to air conditioning, proximity to medical care, EMS availability, cultural norms, and even the robustness of local churches, civic organizations, and other indicators of strong "social infrastructure."

As such, Ward worries that the prevalence of research and media attention on the urban heat island effect has led to some misguided assumptions about rural areas — where temps may be lower, but a multitude of other factors exacerbate risks. For example, an individual living in a rural mobile home with no AC — exposed to the underappreciated dangers of persistently high overnight temperatures — is likely at higher risk for heat-related illness than an upper-income urban apartment dweller, though the urban neighborhood may be 10 degrees warmer. The Heat Policy Innovation Hub, under Ward's leadership, is hoping to bring renewed attention to the issue and has identified rural interventions as one of its primary focal areas.

Ward's perspective on heat mitigation and intervention is influenced by the work of sociologist Eric Klinenberg, who has studied why demographically similar neighborhoods experienced drastically different mortality rates during the 1995 Chicago heat wave. His research indicates that the key difference between these neighborhoods was the robustness of their social infrastructure — defined as "the people, places, and institutions that foster cohesion and support." During a heat wave, Klinenberg has written, living in a neighborhood with strong social infrastructure "is the rough equivalent of having a working air conditioner in each room."

Chicago is a far cry from Scotland County, North Carolina, but Ward suspects the same principles still apply. She has worked closely with the NCDHHS and community partners like Cox in their efforts to address heat impacts in the Sandhills region. A key aspect of their approach has been to "plug into the already existing networks that have been effective forever in rural areas": from churches, civic organizations, and local media to informal community groups and the bonds between neighbors. Harnessing the power of these social networks is "how rural people have dealt with almost everything," said Ward.

From May through September, the NCDHHS publishes weekly heat reports containing information on heat-related ED visits, including demographic data and Sandhills regional impacts; they also provide advance notice to Sandhills community partners when the heat index is forecast to climb dangerously high. From there, it is up to community partners to "reach their communities in the way that they know works best," said Hatcher. In 2018, partners from four Sandhills counties worked with the NCDHHS to create outreach plans for the local populations they determined to be most susceptible. The methods and priorities of a partner working in a county with a large farmworker population, for example, will be different from those of a partner working in a county with little agriculture but a large number of older adults.

Ward is enthusiastic about the work she has observed so far in the Sandhills region: "I've got to tell you, the people that work at the county level — in my whole career, these are the most innovative people I've ever met, because they do incredible work with almost no resources. You've got emergency management and public health people that are wearing five or six hats."

Cox certainly fits the description. In addition to managing a major grant initiative, she publishes regular columns in the local newspaper, hosts monthly programs on two local radio stations, shares public health information on social media, presents regularly to local groups and organizations, and conducts outreach at community events — often on Saturdays. During the hot summer months, she leverages all of these platforms to share up-to-date heat data, alerts, and safety information; she also reminds residents of the importance of simply checking in on one's neighbors during a heat wave. One small indication of her creativity and dedication to the cause: Cox sometimes even includes heat safety reminders in her work voicemail message. "I'm always looking for a way to get that message out there," she said.

I would like to say that we are going to air-condition the world, but that probably won't happen. And even if it did, it's not going to happen tomorrow — and it's going to be hot tomorrow.

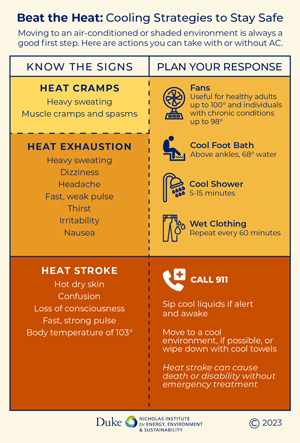

Sandhills community partners also distribute a variety of educational and prevention items, courtesy of the Heat Policy Innovation Hub and NCDHHS. These include magnets, water bottles, towels, and paper fans that are printed with heat safety information and cooling strategies for those without access to AC; items are available in either English or Spanish. Ward views this as "critical information," especially for lower-income rural populations. "I would like to say that we are going to air-condition the world, but that probably won't happen," said Ward. "And even if it did, it's not going to happen tomorrow — and it's going to be hot tomorrow."

Cox works frequently with rural churches as part of her efforts to reach older adults, one of her target demographics, and has found the paper fans to be a surprise hit: "Everybody loves these fans. I'm not kidding." Sandhills partners publicize the locations of designated cooling centers — usually libraries and community centers — though they recognize that distance and transportation present barriers for some, and these locations are not an option for evening relief. To address this issue, Cox has helped older adults apply to receive electric fans and window AC units from the local Aging Advisory Council, through a program at NCDHHS.

True to their name, the Heat Policy Innovation Hub is also working to assist both counties and states with policy development and emergency planning. This summer — in partnership with the NCDHHS, the NC State Climate Office, and the NC Office of Recovery and Resilience — they convened representatives from 10 NC counties to discuss the incorporation of heat into county hazard mitigation plans. Eventually, the group intends to create a customizable template, which will be made available to all 100 NC counties. If widely adopted, this county-level planning would allow for the coordination of a statewide heat alert system. According to Ward, North Carolina is the only state in the country in which every county has its own hazard mitigation plan. Still, she hopes the work of their coalition might provide "a model for what other states could possibly do, about how to engage with local communities to develop place-based heat mitigation strategies."

In April, Ward and co-author Jordyn Clark published a report that offered guidance on the incorporation of heat-related threats into state hazard mitigation plans (SHMPs). The report found that only 25 SHMPs had sections dedicated specifically to heat. The stakes of such planning are high — and growing higher. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), heat is often responsible for more annual deaths in the U.S. than any other weather-related event [article no longer available online]. Meanwhile, annual average temperatures have climbed; or, as Ward put it: "This is not my grandmother's summer."

Beyond the Sun Belt

While headlines in July were focused on devastating heat waves in Texas and Arizona, attention shifted northward in late August when a "heat dome" led to record-breaking temps in several Midwestern states. Dana Habeeb, Assistant Professor at Indiana University's Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering, has been studying how extreme heat affects cities for over 15 years. "Ten years ago, Portland was highlighted as being vulnerable to heat, which some people found surprising at the time," said Habeeb. Then, in 2021, that prediction was tragically confirmed. These days, Habeeb is particularly worried about extreme heat in the Midwest. "These trends are happening, and no matter where communities are located in the United States, we need to be preparing them to deal with extreme heat," she said.

These trends are happening, and no matter where communities are located in the United States, we need to be preparing them to deal with extreme heat.

Habeeb is the principal investigator for Beat the Heat, a program that guided two Indiana communities through the creation of targeted heat response plans. The program was developed by Indiana University's Environmental Resilience Institute and funded by the Indiana Office of Community and Rural Affairs. Clarksville, a small suburb of Louisville, and Richmond, located in rural Wayne County, were selected to participate in the two-year grant program. The program supported both communities in the hiring of heat relief coordinators, who led the data-gathering, organizing, and extensive community outreach which informed the development of the plans.

A rural Midwestern county may seem to some like an unusual setting for such intensive extreme heat planning; however, even before this summer's heat dome, the Beat the Heat team found that many Richmond residents were struggling to stay cool. One in three respondents to a community heat survey reported experiencing a barrier to using their home AC — most often citing utility and repair costs. According to Habeeb, one respondent shared that she occasionally used her car to give her children relief from their un-air-conditioned home.

Program organizers tested a variety of interventions over the course of the grant period: a social media campaign for extreme heat awareness, designating cooling centers for high-heat days, the incorporation of extreme heat alerts into an existing text-based county emergency alert system, conducting heat illness trainings for local healthcare and social service providers, and much more. The City of Richmond Heat Management Plan offers a detailed summary of ongoing efforts, as well as planned future initiatives. Habeeb stressed that there is no "one-size-fits-all solution" for heat mitigation and adaptation, and emphasized the importance for other communities to tailor interventions to the specific needs of their local populations.

City and county officials may look to two new tools from the federal government for a broad overview of local risks. The EMS HeatTracker [no longer available online], released in August on the National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) website, provides information on how every U.S. county's rate of heat-related EMS activations compares to the national average over the previous 30 days. (At the time of this article's publication, 9 of the 10 counties with the highest rates of heat-related EMS activations were rural; urban residents, however, represented a far greater share of total heat-related deaths.)

In April, the Census Bureau released Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat — developed in collaboration with the Arizona State University Knowledge Exchange for Resilience (KER) — which draws from a massive national sample of household-level data. Users may view the number and rate of households within a state, county, or census tract who have three or more risk factors relevant to heat vulnerability (such as housing quality, income level, and transportation access). The CRE for Heat does not factor in local temperature forecasts but, rather, estimates the susceptibility of communities if exposed to extreme heat.

As such, the tool turns up some surprising results; for instance, three of the ten counties with the highest rates of households with three or more risk factors are in rural South Dakota. However, KER Executive Director Patricia Solís — who helped develop the tool — hopes it will be used for more than rankings and comparisons. "When you drill down, you are going to find some people who are okay, and some people who are not okay, in all of these places; what the dataset helps you do is really try to uncover why," said Solís. Moreover, she noted, even those who are not particularly susceptible will be impacted by extreme heat eventually: "You will have exposure, just like we saw during the pandemic. Certainly some… communities were hit harder than others, but it did not leave anyone untouched."

Protecting Workers

One group that has been hit far harder than others is also among the most essential to some rural economies. A 2016 analysis of fatality data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that farmworkers are 35 times more likely to die from heat-related causes than other U.S. workers. There is the simple fact of prolonged, physically demanding labor in the shadeless fields. But then there are other, less obvious factors related to what Amy Liebman — Chief Program Officer for Workers, Environment, and Climate at Migrant Clinicians Network (MCN) — calls an often "precarious work situation."

Both groups are coming to their jobs with the need to make money in order for them to survive and their families to survive — that's number one on their mind.

According to Liebman, many farmworkers are immigrants — some with only temporary H-2A work visas or no visas at all. "Both groups are coming to their jobs with the need to make money in order for them to survive and their families to survive — that's number one on their mind," she said. Such workers are not particularly eager to "rock the boat" by reporting unsafe conditions. Also, farmworkers are often paid at piece-rate (the more you pick, the more you make), which disincentivizes breaks for water, rest, and shade. MCN has long advocated for the creation of a federal heat standard to mandate such breaks under hazardous conditions; in 2021, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) initiated a rulemaking process, which typically takes several years.

Another major factor contributing to farmworker susceptibility is lack of acclimatization — the gradual process by which our bodies adjust to new temperature norms. H-2A workers often arrive at farms at the peak of harvest and begin working long days immediately, Liebman said. According to OSHA, "over 70 percent of heat-related deaths occur during a worker's first week." (This need for acclimatization also explains why even relatively mild, early-season heat waves can lead to elevated rates of heat-related illness — as Kathie Cox experienced that May evening in Laurinburg.)

Mary Jo Ybarra-Vega is the Outreach and Behavioral Health Coordinator at Quincy Community Health Center in rural Grant County, Washington. She coordinates a team of promotores de salud (Spanish-speaking community health workers), whom she views as essential for effective outreach to farmworkers on heat safety and other issues. Over the course of two months this summer, Ybarra-Vega and her team provided outreach to over 1,500 farmworkers, including many H-2A workers. They approach the work with a "popular education" philosophy, offering fun, hands-on experiences such as educational games and skits. "We bring down the health literacy level to the population that we're working with," said Ybarra-Vega, noting that some workers may have lower levels of formal education. In return, farmworkers "ask them [promotores] questions that they would've never asked the doctor."

Faced with multiple escalating occupational hazards — from extreme heat and wildfire smoke to pesticide exposure and infectious disease — effective public health outreach can provide critical support to workers in understanding their symptoms and risk factors. Recently, Ybarra-Vega was contacted by a woman who shared concerns about a possible COVID outbreak among a number of her coworkers; they reported experiencing headaches and nausea. "I started thinking…yeah, it could be COVID, but maybe it's something else. It kind of sounds like heat," said Ybarra-Vega. She encouraged the group to come in for testing, and her suspicions were eventually confirmed.

The impacts of "chronic heat stress" are not limited to temporary symptoms like headache and nausea. In recent years, Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Cause (CKDu) has emerged as a leading killer of young, working-age men in Central America; research indicates occupational exposure to extreme heat is playing a significant role. MCN's Heat-Related Illness Clinician's Guide offers an overview of health impacts on farmworkers, including additional information on CKDu, best practices for treatment and follow-up, and social determinants of health.

Postal carriers, construction workers, and others who work outdoors face similar heat-related occupational risks — and many indoor workers are susceptible, too. In North Carolina, for example, working-age men represent the largest proportion of heat-related ED visits; Ward suspects many of those men are employed in indoor manufacturing facilities, which often lack AC. Whatever the occupation, Ward stressed that "heat-illness and death are 100% preventable." As she wrote in a recent column: "Key to prevention is to first recognize the risk. Second is education and awareness of practical prevention measures. And third: action."

Making an Impact

A few months after publishing her "embarrassing" personal experience with heat-related illness in The Laurinburg Exchange, Kathie Cox received a surprising note in her email inbox. It was from the nurse at a local indoor manufacturing plant. Cox had previously visited the facility for an outreach event; she remembered that it was warm and there was no AC.

The nurse shared that there had been two incidents of heat-related illness among their workers in recent years — so when she read Cox's column, it struck a chord. She had copied the article and emailed it to all local employees, in addition to the company's Corporate Health and Safety Director. He, in turn, had sent it to all the company's locations in the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

"I wanted you to know that your article was being shared with thousands of people around the world," wrote the nurse. Cox, who plans to retire at the end of this year, described this unexpected impact as one of the "thrills" of her long career. She later received a letter of commendation from the international company.

The email concluded: "Also I am glad to report that we did not have any heat-related illness this year."