Nov 20, 2019

Office-Based Spirometry: Key to Diagnosing Rural COPD Patients

Related Article

Diagnosing the

Rural COPD Patient: Ask About Symptoms, Use

Spirometry

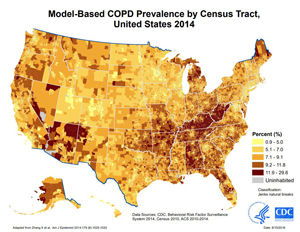

Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, is a condition

with almost double the prevalence and mortality rates in

rural areas compared to large urban centers. In 2018, the

condition was one focus topic for the National Advisory

Committee on Rural Health & Human Services. In its

policy brief, the Committee noted stakeholders had

emphasized "the underutilization of spirometry to

diagnose COPD in rural primary care clinics. The

Committee also learned about the need for more spirometry

testing in primary care settings, especially for areas

that report higher COPD prevalence, hospitalizations, and

deaths."

Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, is a condition

with almost double the prevalence and mortality rates in

rural areas compared to large urban centers. In 2018, the

condition was one focus topic for the National Advisory

Committee on Rural Health & Human Services. In its

policy brief, the Committee noted stakeholders had

emphasized "the underutilization of spirometry to

diagnose COPD in rural primary care clinics. The

Committee also learned about the need for more spirometry

testing in primary care settings, especially for areas

that report higher COPD prevalence, hospitalizations, and

deaths."

Dr. Barbara Yawn has had similar concerns about the under-use of spirometry. She has published extensively on that subject and other COPD issues. With a career that first included a rural family medicine practice, followed by time as a Bush Foundation Fellow and getting a master's degree in statistics, she then created a research department in a large clinic and hospital in southeastern Minnesota that cared for many rural patients.

"At the time I started the clinic's research arm, almost all research in medical journals was coming out of urban academic medical centers," Yawn said. "Patients recruited for these studies always seemed to have one disease, enough money to buy their medications, and had time to come back for follow-up appointments. They certainly weren't representative of the patients I was caring for in my rural practice. I decided I wanted to do research for patients with the conditions we saw in the real world — like asthma and COPD — that had multiple comorbidities and real-world barriers to care."

"Back then, if a patient was diagnosed with COPD, it was considered a death sentence," she pointed out. "I wanted to see if we could help primary care physicians and other clinicians better learn how to diagnosis and treat COPD. I wanted them to understand there is hope for improving the lives of people with COPD."

Yawn, who is now the COPD Foundation's Chief Science Officer, emphasized that spirometry done on the front lines in primary care offices can be key to the accurate diagnosis and treatment of COPD and other lower respiratory diseases. In 2007, she and her colleagues published a study on office-based spirometry performed in primary care offices throughout the country. Yawn recalls that nearly 30% of the practices were in rural areas. The investigators concluded that "U.S. family physicians can perform and interpret spirometry for asthma and COPD patients at rates comparable to those published in the literature for international primary care studies, and the spirometry results modify care." With continued research and participation as an expert in numerous national meetings and studies over the past decade, Yawn persists not only in her advocacy for primary care office-based spirometry, but using other evidence-based approaches to bring best treatment practices to patients with COPD.

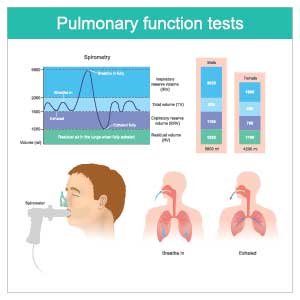

Spirometry Basics

As the standard for establishing a diagnosis of COPD, spirometry measures a patient's lung capacity. The spirometer is a medical device that measures the largest amount of air a patient can take in and then also blow out. This 2½-minute video from National Jewish Health demonstrates desktop spirometry testing.

Two abbreviations are used to describe the amount of air that's exhaled: the FEV1 and FVC. The FEV1 is how much air a patient can force out of their lungs in one second, or the forced expiratory volume. The FVC, or the forced vital capacity, is the total amount of air a patient can force out of their lungs when they empty their lungs as completely as possible. In patients with normal lungs, that usually requires 6 to 10 seconds. For people with COPD, more time is often required to "empty" their lungs.

To establish a diagnosis of COPD, the FEV1 and FVC must be compared: A ratio between FEV1 and FVC of less than 0.7 is considered diagnostic of obstructive lung disease. The results of a 2019 study endorsed the clinical importance of this ratio.

Normal values of FEV1 and FVC are predicted by age, height, sex, and other parameters. Spirometry results are then reported as a percent of that predicted normal.

| Table 1. Severity of Airflow Obstruction in COPD | |

| Mild | FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted |

| Moderate | FEV1 = 50 to 79% predicted |

| Severe | FEV1 = 30 to 49% predicted |

| Very Severe | FEV1 = 30% predicted |

Source: University of Michigan's COPD Treatment Guidelines

Based on an international standard referred to as the GOLD criteria, a common language around the severity of COPD airflow obstruction has developed (Table 1). In their everyday work, clinicians might use these spirometry measures to speak with one another — and sometimes in conversations with their patients — by referring to the FEV1 percent predicted value itself. For example, if a patient care hand-off happens, one clinician might say to the other something like, "She's always done really well with her COPD, but Jane Doe has been in the hospital for three days now with a bad community-acquired pneumonia. A year ago, her FEV1 was about 40 percent predicted." The objective measure of lung function may be helpful for inpatient care and discharge planning when it's partnered with an understanding of the patient's symptom burden and functional ability since those elements can vary widely for any range of FEV1 measures.

Lung capacity testing is often also referred to as pulmonary function testing, or PFTs. This testing not only includes spirometry but also other special measures of lung function.

"Spirometry is important and very doable in practice,"

Yawn said. "Yes, it's disruptive to patient flow in a

busy office, but no one hesitates to order an EKG and

that is also disruptive. I don't know any primary care

practices that say, 'Nope, we don't know how to do EKGs,

I can't do those.' Everybody knows how to do those and

knows how to fit them into the practice workflow. Doing

spirometry for shortness of breath should be exactly the

same. Once you recognize the value of the test, you're

going to figure out how to work it into the practice."

Chaffee Tommarello shared where spirometry fits into a practice workflow that includes a community-based pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program. Tommarello, a certified asthma educator, registered pulmonary function technologist, and registered respiratory therapist, works at The Breathing Center, part of the Cabin Creek Health Systems and the Grace Anne Dorney Pulmonary Rehabilitation Center in Dawes, West Virginia. Doing a patient's first spirometry or pulmonary function testing is part of her daily work.

"When we do a patient's first spirometry testing as a part of their pulmonary rehabilitation evaluation, I'd say about 20 to 30 percent of those patients don't have COPD," she said. "But 10 percent of the time, they will have abnormal lung values, like those that match up with other lung diseases, for example, restrictive lung disease."

In addition to establishing a COPD diagnosis, Tommarello emphasized that this scenario is a perfect example of why spirometry is important to all patients referred with breathing problems: to establish the correct diagnosis in order to guide treatment. Patients with breathing problems not caused by COPD can also benefit from outpatient respiratory rehabilitation services, as research from around the globe indicates.

She also said that Cabin Creek staff are on watch for patients with breathing problems since Cabin Creek's health system — a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) with six sites — cares for the area's rural population in a state with significant prevalence of lower respiratory diseases, especially COPD. Identification of patients is expedited with a standing order set that allows evaluation of a patient with a breathing problem, sometimes even as they sit in a waiting room and are noted to have breathing problems.

"Having that flexibility to help our clinicians identify patients with chronic lung problems is really important in an area like ours here in West Virginia where we have so many patients with lung disease," Tommarello said.

Frontline Rural Spirometry: A Must for Patients with COPD and Other Respiratory Conditions

Some experts have reservations about spirometry testing and interpretation performed in primary care offices. Yawn shared how those concerns can be mitigated so that the lung health of primary care patients can still be addressed.

"While some primary care practices have not produced high-quality spirometry testing and interpretation, that concern should not be used to move spirometry out of primary care," Yawn said. "For many patients in both rural and other regions of the U.S., primary care is their only source of healthcare. Patients deserve that their primary care includes spirometry. What would we do if a site has quality problems with chest X-rays or EKGs? We'd find ways to educate and support better results. We need to recognize the vital importance of spirometry for lung health and support its use in the same way in all primary care clinics. I am unwilling to accept inadequate care because office-based spirometry is not supported in primary care practices."

For rural offices interested in having spirometry available, Yawn provided a brief overview of required equipment, staffing needs, and interpretation:

-

Equipment

Modern spirometers are affordable for primary care practices and tests are reimbursable when coded appropriately.

-

Staffing

A physician or advanced practice provider isn't needed to administer the test. It doesn't require a nurse or a respiratory therapist. Instead, laboratory personnel, medical assistants, and even receptionists can be trained to obtain high-quality test results. Traditional off-site 1- to 3-day courses are rarely needed. Research has shown shorter programs or even online courses can train staff to competency for completing spirometry. Train two to three staff in order to cover absences.

-

Test Interpretation:

Most of today's spirometers have result readouts for the few basic lung capacity measures needed to establish a probable diagnosis of COPD. The spirometry software will also usually have air flow loop patterns that will show how a test might be suboptimal, for example, if the patient coughed or had poor effort.

Specifically emphasizing spirometry interpretation, Yawn offered additional comments.

"Just like most clinicians know they shouldn't depend on the EKG machine's interpretation readout, they shouldn't trust a spirometer's result readout without over-reading the results and changing them when they're not accurate for that patient and their situation," she said. "That means that clinicians need to know the basics of spirometry interpretation just like they need to know the basics of EKG interpretation."

Rural Access to Pulmonary Function Testing, Respiratory Care Services, and Spirometry

Using 1998 Medicare Part B data for Alaska, Idaho, North and South Carolina and Washington, a 2006 report based on rural-urban commuting codes found that Medicare beneficiaries' median distance to pulmonary function testing was 30.8 miles for isolated rural areas; 33.4 miles for small rural; 9.7 miles for large rural;, and 8.4 miles for urban.

A 2018 policy brief issued by the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center looked at 2016 Medicare data to examine respiratory care service availability. They found that about 16 percent of Critical Access Hospitals had no respiratory care services or respiratory therapists, in contrast to 5 percent of rural and 3 percent of urban Prospective Payment System (PPS) hospitals.

Another 2018 report — from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — looked at several rural-urban health disparities. The report noted that slightly more than 27 percent of rural Medicare Advantage plan beneficiaries age 40 and older with either a new diagnosis of COPD or "newly active COPD" had not received "appropriate spirometry testing" for disease confirmation compared to their urban counterparts.

Next Steps for Increasing the Use of Spirometry Testing for COPD

From its background work, the National Advisory Committee noted that many stakeholders expressed concerns about the need for increasing the education opportunities for rural primary care clinicians that include the diagnosis of COPD and spirometry use. Academic reports and studies support those concerns. A 2012 paper presented at a specialty conference on the topic of doing spirometry in primary care offices included audience comments. One academic pulmonologist from Vermont suggested that to expect quality testing, proper education of the medical workforce needs to happen: "We in the medical education community unfortunately do a poor job of teaching medical students simple lung function and simple spirometry."

That academic voice from a largely rural state does not stand alone. Similar-themed comments are found in a 2013 paper, this time analyzing an urban academic primary care practice. The investigators' research goal was better understanding of the attitudes and barriers around the use of spirometry for diagnosing suspected COPD. The conclusion is limited by the fact that the group was small: 12 practitioners, all from the same academic institution. The research found no barriers to spirometry access. Alternatively, results showed that spirometry was not used because the providers were skeptical about its usefulness in the diagnosis of COPD. These results led the researchers to suggest that "a first step toward increasing the use of spirometry among primary care physicians is to have them believe in its utility in the diagnosis and management of COPD."

To bridge the rural knowledge gaps, the National Advisory Committee suggested that the Secretary and the Department of Health and Human Services "undertake a national campaign to educate rural primary care providers and individuals with COPD symptoms about rural-urban disparities in COPD outcomes…and referral for effective treatments to help manage the disease" through established HRSA-funded Area Health Education Centers (AHECs) and CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs).

Yawn provided additional comments about educational needs that aligned with those offered by the Committee.

"All patients need access to adequate lung healthcare and assessment," she said. "That means that primary care physicians and other clinicians need to have education about spirometry included in their training programs. For physicians, there are opportunities in medical school and residency as well as for nurse practitioners and physician assistants in their training programs."

Yawn highlighted that these educational needs around lung health not only include healthcare practitioners, but she also emphasized others who should also take on the responsibility for the lung health of patients.

"It needs to be a priority for health systems, clinics, professional societies, and CME/CE providers," Yawn suggested. "For too long we have failed to focus on the lungs except, perhaps, for asthma in children. Without the lungs to get the oxygen into the body, the heart and the rest of the organs have little chance to function."