Nov 06, 2019

Creating a Consortium to Combat the Opioid Epidemic in Ohio

by Allee Mead

From 2013 to

2017, Ohio had a drug overdose mortality rate of 47.6

deaths per 100,000 people aged 15-64; in comparison, the

national rate was 25.1, according to Drug Overdose Deaths

in the United States. In addition, poverty, coupled

with the scarcity of facilities that treat opioid use

disorder (OUD) and the lack of providers with

medication-assisted treatment waivers, are barriers to

receiving OUD care in this region.

From 2013 to

2017, Ohio had a drug overdose mortality rate of 47.6

deaths per 100,000 people aged 15-64; in comparison, the

national rate was 25.1, according to Drug Overdose Deaths

in the United States. In addition, poverty, coupled

with the scarcity of facilities that treat opioid use

disorder (OUD) and the lack of providers with

medication-assisted treatment waivers, are barriers to

receiving OUD care in this region.

Matthew Courser, PhD, Senior Research Scientist with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), helps communities in Ohio work with data and build capacity to address public health issues. "At the state and community level, we had prevention, treatment, and recovery pretty much siloed," Courser said. "Communities really weren't able to collaborate across the continuum of care."

Courser added that, while communities he had worked with had collected some data, a key gap was that strategic planning around OUD was not data-driven.

Holly Raffle, PhD, MCHES, a professor at Ohio University's Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs, said she saw a shift in federal funding where, instead of funding the states that then pass the money down to the communities, federal organizations started funding communities directly.

However, Raffle noted that the communities with the greatest needs for funds often don't have the capacity to apply for these federal funds: "When you have a community who is basically just trying to stay afloat with all the issues that they have, the idea of writing a grant application – which could be a lot of time investment for something that might happen – is really tough."

In addition, rural communities that receive grants might not know how to complete tasks like invoices or budget revisions. "You're working with rural communities, and you have that capacity issue," Raffle said. "It's not that the communities don't want to do it or they're not ready to do it. It's that they don't have that experience."

We wanted to ensure that Ohio's rural and Appalachian communities had access to those dollars.

"We wanted to ensure that Ohio's rural and Appalachian communities had access to those dollars," Raffle said.

A Unique Grant Application

Ohio University (OU) and PIRE have worked together for about ten years now, providing training, technical assistance, and leadership development to local communities. When the HRSA Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP) planning grant application period opened in 2018, the two organizations decided to apply. While it's designed for rural communities, RCORP allows urban organizations to be the lead applicants as long as they partner with rural organizations and all services funded through the grant are directed solely to benefit rural communities.

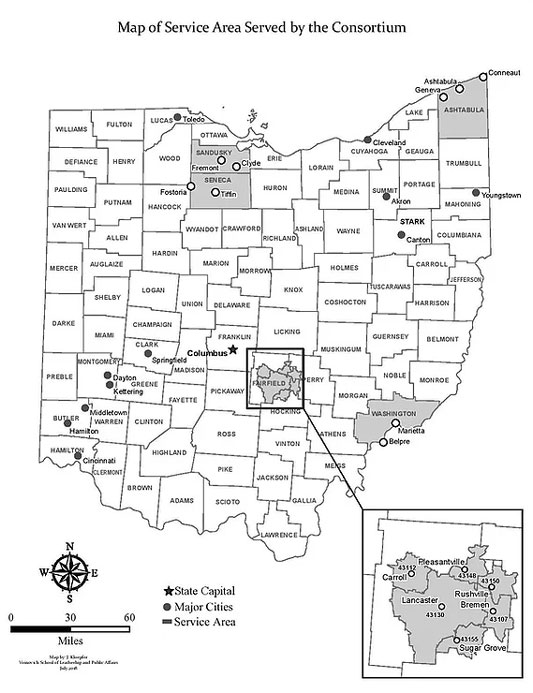

In order to maximize their reach, OU and PIRE chose to apply separately, each planning to serve two counties if awarded, because they determined that $200,000 wasn't enough money to serve all five counties in their collective service area. In their applications, they wrote about their plans to collaborate with each other and serve Ashtabula, Fairfield, Sandusky, Seneca, and Washington counties if the grants were both funded. Some of the costs – like website hosting and development or renting a meeting space – became duplicative, so OU and PIRE could serve five counties across the awards instead of two counties each.

Drug Overdose Mortality Rates in 5 Ohio Counties

According to Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, the counties served had the following drug overdose mortality rates (deaths per 100,000 people aged 15-64) from 2013 to 2017:

- Ashtabula: 53.8

- Fairfield: 27.4

- Sandusky: 40.8

- Seneca: 32.2

- Washington: 38.9

Kiley Diop, Public Health Analyst at FORHP and project

officer for the Ohio University grant, said,

"Those applications were reviewed

independently, and then, by each of their own merits, the

applications were awarded."

Both organizations were each awarded a $200,000 grant, so the two grantees signed a shared-services agreement to define their complementary collaboration.

"[The collaboration] is a way to enhance value of federal investments as a way to increase impact without requiring an additional outlay of federal resources," Courser said.

Creating a Consortium

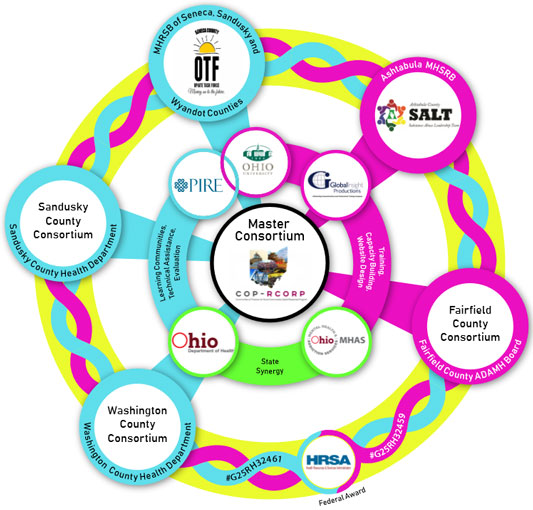

When the grants were braided together through the shared-services agreement, the five communities called their initiative the Communities of Practice for Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (CoP-RCORP). One requirement of the grant was to form a consortium. Using the hub-and-spoke model, CoP-RCORP has a master consortium (OU, PIRE, and project directors from each county) and each county has a consortium that brings together community partners like county boards and health departments. The Washington County Consortium, for example, consists of law enforcement, healthcare and behavioral health providers, schools, local health departments, drug courts, and municipal courts.

Courser explained that developing a local consortium led counties to form partnerships with organizations that they might not have partnered with otherwise and improve their reach across the full continuum of care. He said, "It's something that's going to give them a lasting benefit beyond any sort of HRSA funding."

The counties have a weekly technical assistance call with either OU or PIRE and a monthly videoconference with the master consortium members. Shae Sprigg, Local Public Health Emergency Preparedness Coordinator at Washington County Health Department, said that these calls are very helpful, since consortium members can share struggles and hear what other members have done in similar situations.

How OU and PIRE Support the Five Counties

Through the RCORP grant, Ohio University and the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation provide the following services to the master consortium members:

- Training and leadership development

- Technical assistance and evaluation

- Financial resources to support the counties' planning process

- Wraparound support

- Website where the counties post meeting notes, workplans, and other resources

"They have more experience in getting there and

getting set up and they've been extremely helpful in

sharing," Sprigg said, adding that the

Washington County Consortium is newer than some of the

other consortia.

[The other consortium members] have more experience in getting there and getting set up and they've been extremely helpful in sharing.

After forming a consortium, the counties completed a needs assessment. Courser said the assessment challenged what consortium members knew about OUD in their communities. "We had a couple communities tell us that they actually came away from the process knowing a lot more about their community than they otherwise would have," he said.

The consortium members recently finalized sustainability plans and focused on workforce development. Courser said they're also building a data system at the state level.

Accomplishments and Recognition

In 2019, Diop,

Courser, and Raffle, along with other FORHP staff and an

RCORP grantee from Michigan, gave a presentation at the

National Rural Health Association (NRHA) Annual Rural

Health Conference in Atlanta. FORHP presented its opioid

funding programs and highlighted the work of

collaborative grantees like CoP-RCORP.

In 2019, Diop,

Courser, and Raffle, along with other FORHP staff and an

RCORP grantee from Michigan, gave a presentation at the

National Rural Health Association (NRHA) Annual Rural

Health Conference in Atlanta. FORHP presented its opioid

funding programs and highlighted the work of

collaborative grantees like CoP-RCORP.

"The partnership that OU and PIRE have together was one of the first examples that came to mind to highlight at the conference," Diop said. "It's a really innovative approach of being able to serve more communities."

Diop also praised the CoP-RCORP website (no longer available online), in which the counties list webinars, memoranda of understanding, and master consortium meeting notes, among other documents. "They are incredibly transparent to the communities on everything that is going on," she said.

The partnership that OU and PIRE have together was one of the first examples that came to mind to highlight at the conference. It's a really innovative approach of being able to serve more communities.

The planning grant has taught Sprigg that "we have more need for data than what we realized, and we don't have access to data that we really need in order to do this work." For example, the Washington County Consortium currently doesn't collect data on how many times emergency medical services have administered Narcan for an opioid overdose or how many people come to the emergency department for an overdose. Thanks to this grant, the county's working on improving its data collection.

When the opportunity came up to apply for the RCORP implementation grant, Courser and Raffle asked the five consortium members if they wanted to continue to work collaboratively. All five members wanted to continue the consortium model, saying that they like learning from and supporting one another, sharing resources like an evaluator or fiscal agent, and splitting the costs of training or hiring a media company for a stigma reduction campaign. Raffle is interested to see how many shared-services agreements continue after the implementation grant.

OU and PIRE individually applied for the implementation grant and were awarded $1 million each, so they're working with FORHP to formalize complementary collaboration on this grant; then they'll put the blueprint they developed through their planning grant into action. The implementation workplan includes prevention, treatment, recovery, and sustainability activities across the five-county service area.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

OU and PIRE selected the five counties after interviewing seven. The interview process allowed the organizations to make sure the partnerships were "a mutually good fit," Raffle said.

Raffle added that it can be a difficult conversation to ask communities to sign on to a project like this not knowing if they'll be funded. For example, if OU had been funded instead of PIRE, then only the two counties that OU included in its grant application would have received funding, and vice versa. The fifth county would only receive funding if both OU and PIRE were funded.

The consortium members have had videoconferencing meetings but met face-to-face last June. Courser called that meeting "transformative" and recommended that other consortia meet in person sooner in the planning process.

Consortium members told Raffle that they preferred "homework assignments" to connect with other members. While they can call their peers at any time for advice, they preferred being asked to schedule a call and discuss, for example, their workforce development plan and keep a record of their conversation.

In addition, Sprigg said that stigma is still an issue in her county. "Everyone's touched by this one way or another. It might be a niece or a nephew or a greatgrandchild or a brother or sister, but it's crazy that there is still such stigma around something that is so commonly spread, even in these rural communities," she said.

Sprigg visits organizations like harm reduction programs and pharmacies to learn how they're combating the opioid crisis and how her organization can better promote their work. In addition, the Washington County behavioral health board travels to other counties to see what they're doing well (for example, in harm reduction and opioid overdose response) and to bring those ideas home.

Another challenge is that local entities may have different business practices than larger organizations like OU, Raffle said. She added it takes patience and sometimes creating a template to help communities succeed.

Trust is a key component of a consortium like this. "Over time we've built a significant amount of trust, both with the folks who work together within local consortium organizations and between the consortium organizations themselves," Courser said.

Raffle said that larger organizations, like research universities or technical assistance programs, need to look at communities as equals, "not doing stuff to communities or for communities but with communities."