Oct 23, 2019

Translational Science: Research with Results that Touch Rural Populations

Related Article

NIH

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences:

Involving Rural America in Research

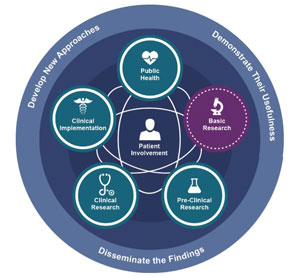

Translation is a common daily activity. We translate pounds to kilos, English to Spanish, and ideas to actions. In order for modern health science research to have an impact, translation is also required. Translation makes sure that scientific discoveries found in the lab can be put to practical use in clinics, hospitals, and communities with an end goal of improving people's health and well-being. For example, some results coming from translation are new ways to diagnose and treat disease, new medical procedures or devices, and even better advice for patients on how to change behaviors in order to live a healthier life.

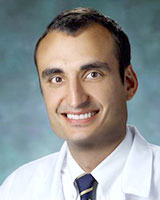

But there is another important element to translational science, as this special field of research is now called: having teams in place that can navigate the complexities of turning science into health. Dr. Michael Kurilla, director of the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Division of Clinical Innovation, explained the agency's goal.

"NCATS is charged with focusing on what previously no one was really paying attention to," Kurilla said. "To translate science, it takes a lot of administrative, operational, and logistical coordination to make sure science gets to the people. We are taking a scientific approach to the steps and processes associated with the translation of science and making them more robust, more predictable, more reproducible in order to reduce the high failure rate we've seen so often in the past when a lot of great ideas got just go so far before they petered out."

Understanding the Work of NCATS

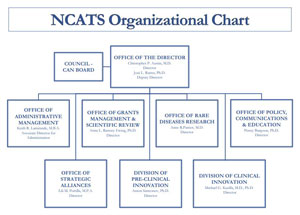

With official origins in 2012, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) is one of 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The center "strives to develop innovations to reduce, remove or bypass costly and time-consuming bottlenecks in the translational research pipeline in an effort to speed the delivery of new drugs, diagnostics and medical devices to patients."

The agency has several offices and divisions that focus on getting NIH's cutting edge discoveries to the people. One division in particular, the Division of Clinical Innovation, "plans, conducts and supports research across the clinical phases of the translational science spectrum."

The Clinical Innovation division has many roles and oversees many activities, including the Clinical Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program. This program offers funding support for a national network of collaborative regional medical research institutions — referred to as CTSA hubs — all working towards a mutual goal of getting "more treatments to more patients more quickly."

Though a variety of funding opportunities are available, three main CTSA program awards include the UL1, a cooperative agreement; the K2 support award for clinicians, and the TL1 award for those interested in translational science careers.

CTSA Program

| Award Level | Category | Description |

| UL1 award | Cooperative agreement | Supports clinical and translational research. Administratively linked to other projects |

| K2 award | Research Career Program | Supports selected newly trained clinicians for a clinical and translational research career |

| TL1 award | Training Programs | Supports research training experience for pre-doctoral trainees interested in multi-disciplinary clinical and translational research career. Administratively linked to other projects |

With their clinical research focus, CTSA hubs are collaborating with rural healthcare organizations and communities through community engagement programs.

| NCATS Strategic Plan |

• Translational science • Collaboration and Partnerships • Education and Training • Stewardship |

| NCATS Goals |

• Conduct/support research

with results that catalyze development and

dissemination of medical interventions. • Advance translational team science by strategically engaging a variety of stakeholders/partners. • Develop creative and cross-cutting translational science workforce • Practice good stewardship of public funds |

| CTSA Program Goals |

• Train

translational work force • Engage patients/communities in all phases of translation • Promote translational research that focuses on the human lifespan and includes attention to disparities of unique populations in need • Increase efficiency and quality of translational research • Advance use of modern informatics |

| Key: Black = Science; Brown = Collaboration and partnerships; Green = Workforce education; Blue = Stewardship | |

NCATS and Research for Rural and Remote Populations

Kurilla shared that one of the agency's goals is to make sure that rural communities and urban areas of need are on the receiving end of translated science. To accomplish that he said new health science discoveries will need to account for lack of sophisticated technology and specialty physicians which practically can't be supported in areas like rural America. This requires translational scientists to think differently about short- and long-term solutions for getting health science discoveries to those areas.

"Right now, in the short-term, telehealth and other approaches like Project ECHO can help bridge care access gaps," he said. "But, for the future, we are much encouraged by the development of new mobile technologies that take advantage of the smart phone's computing ability. These discoveries are not only putting technology right into the hands of patients and primary care providers, but are allowing researchers to include remote patients in their clinical trials."

Kurilla shared several recent discoveries employing mobile technology, for example, Emory University's translational scientists have perfected a process that uses a cellphone photo of a fingernail to calculate a person's hemoglobin. This provides an option for distance monitoring of problems like anemia, a condition sometimes referred to as "low blood" and associated with many chronic medical conditions. Another discovery is a smart phone plug-in that creates an ultrasound wand. With this technology, the wand can "see" into certain body parts, for example being able to detect a blood clot in a vein or stones insides a gallbladder.

Translational Science that Taps Smart Phone Technology: Figuratively and Literally

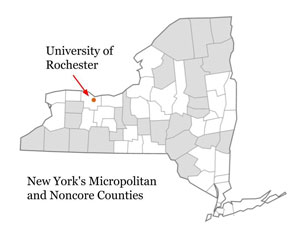

Kurilla's reference to mobile technology is demonstrated by translational research completed by Dr. Ray Dorsey, a neurology professor and researcher at the University of Rochester. Early in his career, Dorsey, a neurologist with a dual MD/MBA, received K2 research support through the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Clinical and Translational Science Institute's CTSA program.

"I was a young Fellow with atypical research interests," Dorsey said. "I was interested in financing trends for biomedical research and how those funding trends translated into interventions that improved the public's health. The K2 award gave me freedom to pursue areas that had not been pursued before."

In a University of Rochester (UR) online course about translational science, Dorsey shared the story of one of his early K2 projects for Parkinson Disease (PD) patients. Realizing that most people possess a mini-computer, the smartphone, he and his fellow investigators worked with a mathematician in the United Kingdom researching the device's ability to measure movements similar to those a neurologist might use in a face-to-face office visit to assess Parkinson Disease (PD). For example, how fast fingers could tap the smartphone screen or even a speech evaluation by having the user vocalize a prolonged "aaahh" can give a neurologist important insight into how PD is impacting that patient's daily activities. After proving that the smartphone could do those measurements well, the team further "translated" that result into a smartphone application for PD research. On the first day the research app was released, 2,000 people signed up.

At its peak, over 15,000 people from all 50 states signed up to engage in our research. And they did it on their own terms using their own devices.

"At its peak, over 15,000 people from all 50 states signed up to engage in our research," Dorsey said. "And they did it on their own terms using their own devices."

Dorsey said that smartphone app has now progressed to a second generation version. Research participants are now able to use the mPower 2.0. Notably, this research phase also needs participants who don't have the disease.

Now director of URMC's Center for Health+Technology, Dorsey said these early K2-supported research experiences influenced the direction of his work. He shared that his center's vision is "researching care for anyone, anywhere," an approach that is designed to include both rural and urban populations of need, especially those who have barriers to coming to a doctor in a clinic setting.

Especially concerning is that so often clinic-based care excludes patients in rural areas who are sometimes older, sicker, and poorer, or those patients who have even more than just these barriers to healthcare.

"When patients come to any doctor's office — or to an office in a major medical center to enroll in research — these patients are generally doing well," he said. "They're also usually socially well connected, stable financially, and medically doing reasonably well. Otherwise, they wouldn't be able to come to clinic. Under those circumstances, we just don't see people who are worse off in society. Especially concerning is that so often clinic-based care excludes patients in rural areas who are sometimes older, sicker, and poorer, or those patients who have even more than just these barriers to healthcare."

Dorsey emphasized that barriers preventing patients from accessing research conducted at urban centers create an unacceptable disparity: exclusion of a population that would contribute to understanding the whole picture of a disease. His activity in a current telehealth project, the PDCNY, is an example of how to include these patients who can't make it to clinic setting.

The Parkinson Disease Care New York, or PDCNY, is virtual care provided by neurologists at no cost to Parkinson disease patients living in New York. Because of reimbursement issues, the care is currently funded by several non-profit, philanthropy, and advocacy organizations. In part, the program is a response to a national 2011 study that showed the importance of neurology care for PD patients: only about 60 percent of Medicare beneficiaries had seen a neurologist, yet connecting with a neurologist was linked to a decreased risk of hip/pelvic fracture, reduced nursing home placement, and the "intriguing finding" of increased survival — findings that make a strong argument for connecting rural and urban PD patients alike with a neurologist. Dorsey said that half of the current 400 PDCNY-enrolled patients are located in Health Professional Shortage Areas throughout the state, with probably 10 to 20 percent specifically in rural areas. Around twenty percent of the patients are homebound, leaving their homes less than once a week.

Dorsey pointed out that PDCNY virtual home-based visits bring a deeper understanding of what's happening day to day in a PD patient's life. That knowledge allows clinicians to better care for a patient.

"Through PDCNY, we connect to our patients and see them in their home," he said. "That allows me to have more insight into their disease state and their personality. I can get an entirely different sense of who they are, what they're like, and what their life with the disease is like when I see them in their home environment. We are also able to see patients who are bedbound. We get a very good picture of those patients who are not doing well."

Dorsey talked about the importance of translational science for people in rural areas but suggested that residents themselves must play an active role in making sure research outcomes are implemented in their locations.

"Policies play a role in getting research results to populations in need," he said. "All this research has huge public health consequences, but policies sometimes are barriers. If rural populations start to demand this care, it will change. There's not a political agenda that wants to decrease access to care for constituents."

Sample of Recent Rural Translational Research Publications

- Breakfast Is Brain Food? The Effect on Grade Point Average of a Rural Group Randomized Program to Promote School Breakfast

- Suboptimal Geographic Accessibility to Comprehensive HIV Care in the US: Regional and Urban–Rural Differences

- HIV Care Provider Perceptions and Approaches to Managing Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Primary HIV Care Settings: A Qualitative Study

- Rural Adult Perspectives on Impact of Hearing Loss and Barriers to Care

- Effectiveness of Ambulatory Telemedicine Care in Older Adults: A Systematic Review

- Eliciting Recovery Narratives in Global Mental Health: Benefits and Potential Harms in Service User Participation

- Rural-Urban Disparities in Health Care Costs and Health Service Utilization Following Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

- Prevalence of Sarcopenia Obesity in Patients Treated at a Rural, Multidisciplinary Weight and Wellness Center