Mar 31, 2021

Exploring the Intersection of Rural Housing Quality and Health: Healthcare Providers and Housing Experts Provide Insight

As a social determinant of

health (SDOH), the impact housing has on health and

well-being extends beyond whether someone has a home or

not. Housing experts suggested that in the rural housing

space, there are unexplored opportunities to join with

public health and medical experts to address housing

quality since all three groups have the same goal:

improved population health and well-being of rural

Americans.

As a social determinant of

health (SDOH), the impact housing has on health and

well-being extends beyond whether someone has a home or

not. Housing experts suggested that in the rural housing

space, there are unexplored opportunities to join with

public health and medical experts to address housing

quality since all three groups have the same goal:

improved population health and well-being of rural

Americans.

Vermont Healthcare Organization's Model: Addressing Patient Housing Needs

Director of Care Coordination and Patient Transitions Lindsay Morse describes housing as a topic only recently integrated into healthcare delivery modeling at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

"As the university and its network transitioned to new care models, we heard phrases like 'high value-based care,' 'population health,' and 'social determinants of health,'" Morse said, noting that her organization is located in one of the most rural states in the country. "Those phrases are more common, but for some of us, they weren't part of regular conversation even five years ago. Now comes a similar transition for housing and healthcare. We've always understood housing as a component of health, but it always seemed daunting and too large to tackle. Not anymore. Housing is a frequent topic in our conversations around healthcare. It's taken on new importance, especially because our community is telling us it's important. In 2019, 58% of our community health needs assessment respondents specifically pointed to housing as a health need."

The University of Vermont Medical Center (UVMC) — and the University of Vermont Health Network which includes several Critical Access Hospitals in Vermont and New York — used these CHNA (community health needs assessment) results as a pivotal engagement opportunity to work with local housing professionals. This engagement was a natural fit with the work of the organization's Community Health Investment Committee, chaired by hospitalist and associate CMO Dr. Steven Grant. Grant explained that he and Morse understood that to achieve competence and understanding around housing, they needed to learn from their community housing leaders and experts.

"Lindsay and I recognized that we needed to first build relations with the housing experts in our community," Grant said. "We did about 30-plus community visits and meetings with the housing trust and the housing authorities. We said to them, 'Can you educate us about what you do and where you see the needs?' We were able to learn about the places, the services, and the financing part of housing and then build a map of those community resources. Importantly, we also learned where the gaps and needs existed."

Grant said that using that approach led to the recognition that a healthcare organization didn't need to be the frontline leaders in projects connecting housing to the health of the organization's patients. Instead, the best fit was to be the medical expert at the table when local housing experts discussed community needs.

Morse said their experiences revealed three key components to successfully integrating housing and health: a physical building, financial support, and social support services.

"We have found that if you don't have all three of these in place all the time, involvement in housing is not sustainable," she said.

Grant explained that UVMC's

collaborative work within the community includes housing

for patients' care transitions in three facilities that

differ somewhat by length of stay. Though the facilities

focus on mostly the recuperative needs of the population

experiencing homelessness, other patients' needs are

accommodated: for example, housing for patients who've

received surgical care or care for major medical

illnesses and need to remain close to services. Morse

added that serving their rural patients was a big part of

the focus on transitional housing.

Grant explained that UVMC's

collaborative work within the community includes housing

for patients' care transitions in three facilities that

differ somewhat by length of stay. Though the facilities

focus on mostly the recuperative needs of the population

experiencing homelessness, other patients' needs are

accommodated: for example, housing for patients who've

received surgical care or care for major medical

illnesses and need to remain close to services. Morse

added that serving their rural patients was a big part of

the focus on transitional housing.

Well-Documented: Health Conditions Linked to Housing Quality

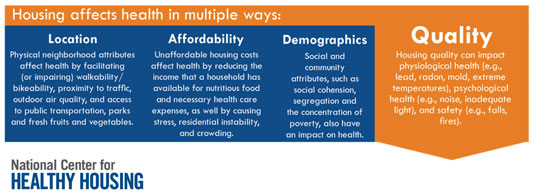

Public health and social science researchers suggest a framework of four pathways or pillars when examining the relationship between housing and health: quality/safety, stability, affordability, and the neighborhood where housing exists. Housing experts use a similar format and language. Sarah Goodwin, a policy analyst for the National Center for Healthy Housing (NCHH), said that quality, affordability, and location [neighborhood] are important when discussing housing and health, but she also adds demographics as a needed category since it includes factors that contribute to housing issues, like segregation and concentration of poverty. Goodwin explained that, of these factors that connect housing and health, NCHH mostly focuses on housing quality.

Goodwin reviewed the common health problems known to have strong links to housing conditions. For example, mold, mildew, or pests can cause or worsen asthma. Another significant housing-linked health condition is lead poisoning in children caused by paint and water pipes. When undetected, this condition results in severe brain and nervous system damage. In addition to these respiratory and heavy metal poisoning problems, multiple structure-related issues inside of homes and rental properties also contribute to falls in older adults, with falls notably an unintentional injury that is actually one of the leading causes of death in both rural and urban areas. A lesser-recognized concern is lung cancer that is linked to radon exposure, since radon is a gas that can accumulate in homes built on uranium deposits. Behind smoking, radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer. Goodwin points out that annual healthcare costs for just these four housing-related conditions total over $300 billion.

More than Nutrition: Housing, Health, and Meals on Wheels America

An example of an organization that gets a firsthand peek at conditions of rural roofs and what's under them is Meals on Wheels America and its network of rural grassroots community-based organizations. Dr. Carter Florence, Meals on Wheels America's senior director for Strategy and Impact, explained that although the organization is recognized for its nutrition program, its work extends well beyond providing meals and includes interventions around socialization, community connections, and housing and safety as part of its More Than a Meal® model.

"The wonderful thing about Meals on Wheels is that our work is about keeping seniors safe at home," Florence said, pointing out that the national network has a significant presence in rural areas with 20% of its programs directly serving rural communities. "That means when you're knocking on the door to deliver a meal, our network members end up being eyes and ears for safety-related issues. If they notice that a handrail is loose or that the stairs are crumbling, that's concerning and they'll begin efforts to help fix that."

Florence mentioned that, in particular, home repairs in rural areas are important in order to promote aging in place.

"For rural seniors, it's often the situation that you're either in your own home or you're in a nursing home because in rural areas it's infrequent that any type of in-between housing alternative is available, like assisted living," Florence said. "Coordinating home repairs then becomes an overall part of our mission to support aging in place."

Repairing Housing Deficiencies for Rural Seniors

Florence said that a number of rural organizations assist Meals on Wheels programs and clients with getting home repair work completed. She noted that Meals on Wheels America itself has a formal relationship with a national foundation that addresses the housing needs of both rural and urban veterans.

Other organizations doing rural repair work are, for example, Rural LISC and its Healthy Housing Initiative. More can be found on a current state listing of home repair organizations collated by the University of Southern California's School of Gerontology. Numerous organizations across the country also have rural seniors' housing repair as a target focus, as shared in the Housing Assistance Council's feature, Home Repair as Healthcare.

In addition to Meals on Wheels America's More Than a

Meal® approach, the organization is also vested in

research activities around housing and safety, Florence

emphasized. For example,

Meals on Wheels America's 2017 safety report found

that many older adults don't report falls because of a

fear of "being sent" to custodial care in a nursing home.

This discovery prompted consideration for additional

research to address the root cause of that fear.

Florence highlighted other findings emerging from the organization's research.

"We've discovered that there's a tremendous

ripple effect beyond the client we're working for,"

Florence said. "When we were able to interview other

members of the household or caregivers, we discovered

that sometimes — more so than for the clients themselves

— the caregivers and family members reported significant

decreased feelings of worry, anxiety, and stress because

home repairs had created a safer environment. This brings

important holistic information to the literature of home

repairs that usually just focuses on outcomes around

falls and activities of daily living."

"We've discovered that there's a tremendous

ripple effect beyond the client we're working for,"

Florence said. "When we were able to interview other

members of the household or caregivers, we discovered

that sometimes — more so than for the clients themselves

— the caregivers and family members reported significant

decreased feelings of worry, anxiety, and stress because

home repairs had created a safer environment. This brings

important holistic information to the literature of home

repairs that usually just focuses on outcomes around

falls and activities of daily living."

Housing and Health: Federal Agency Information

At the federal level, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2030 positions both housing quality and stability — the latter also referred to as instability — within its SDOH stratification.

Nested within Neighborhood and Built Environment, housing quality refers to the physical condition of a person's home: space per individual, air and water quality, presence of mold, asbestos, lead, the structure's age and design, along with any structural disrepair and safety issues.

Housing instability is nested with Economic Stability. The agency suggests there is no standard definition for stability/instability but that it includes the following: forced evictions, financial difficulties meeting rent, spending a large portion of income on housing, overcrowding, and moving frequently between the homes of friends and relatives [couch surfing].

Research indicates that not only do these challenges negatively impact physical and mental health, but they also lessen the ability to access healthcare and are especially traumatizing for children.

Rural Housing Research: Quality-Related Data Gaps

There is minimal data and research

around rural housing and health. NCHH's Goodwin pointed

out that 40% of urban housing has at least one

health and safety hazard — for example, lack of plumbing,

heating, or cooling — yet there is no correlative rural

data point related to that issue.

There is minimal data and research

around rural housing and health. NCHH's Goodwin pointed

out that 40% of urban housing has at least one

health and safety hazard — for example, lack of plumbing,

heating, or cooling — yet there is no correlative rural

data point related to that issue.

"Disparities in health outcomes can be linked to disparities in healthy housing," Goodwin said. "It's very important to be cautious with housing data from national surveys since they don't include much focus on rural housing quality or specific rural hazards. It would be helpful to have not just more information on rural areas but information from the different rural geographical areas across the county. That type of data would help us more accurately identify what healthy housing interventions are needed."

Acknowledging the lack of rural data, NCHH's executive director, Amanda Reddy, also weighed in on the additional complexity associated with rural healthy housing issues.

"Healthy housing by definition is an interdisciplinary problem," Reddy said, noting her organization's 2020-2025 strategic plan includes engaging rural communities and new rural health partners in order to examine healthy rural housing needs. "I would argue that housing is one of the most well-documented social determinants of health and for good reason, especially with a shift to a primary prevention focus and shifting costs from treatment of housing-related health and well-being issues to a prevention lens."

Reddy also shared that past successes still need to be paired with new research and, specifically, rural data.

"We have seen demonstration housing projects with positive results on health outcomes, with positive return on investments from healthcare payers, as well as the broader societal benefits for the families and communities," she said. "But definitely there is a need for a research priority to fine-tune the data needed to better understand the specific housing needs in rural communities."

NCHH's Healthy Homes for All

With its mission of "transforming lives by transforming housing," NCHH is also involved in program and capacity building, research, and advocacy.

Housing Assistance Council: Detailing Elements of the Rural Housing Crisis

Housing experts point out that health impacts of rural housing quality are not a stand-alone topic — it is now part of a larger conversation that is linked to the current housing crisis in rural America. The Housing Assistance Council (HAC) is an organization often called on to define this crisis since its mission is to "improve housing conditions for the rural poor, with an emphasis on the poorest of the poor in the most rural places." Jennifer McAllister, HAC's development manager, provided details of the crisis that includes issues of affordability and inventory, in addition to housing quality.

"Housing affordability is a huge issue for rural communities," she said, noting that some experts suggest it is the biggest housing challenge in rural America. "In the housing industry, we define a homeowner or renter being cost burdened if they're paying 30% or more of their monthly income on housing costs."

She said affordability is even more disparate in places with niche economies.

"Gentrification occurs when those with significant discretionary income build luxury homes, driving prices to levels where local residents are unable to afford housing," she said. "Rural extraction economies [coal, oil, gas, minerals] have a similar impact. In the end, fewer new houses and rental units are built for those with much less income."

Between 2010 and 2018, the number of housing units in rural and small-town communities increased by about 3%, as compared to the nearly 8% in suburban areas, and almost 5% for the country overall, according to a September 2020 HAC policy brief. Of course, because that 3% was not distributed evenly, housing problems exist in large pockets across the rural landscape.

Experts also pointed out that inventory numbers and occupancy rate are as important as where inventory is located: If inventory is too low — or if it is adequate or too high, yet vacant — a community's local service revenue is impacted. In turn, revenue influences growth and development of a community, another contributor to the SDOH of a community and links to population health.

In addition

to affordability and inventory, McAllister said that,

based on information from the 2016 American Community

Survey, nearly 30% of rural housing units have at least

one essential element that either doesn't function

properly or is just lacking. She also pointed out one of

the organization's campaigns, The Last Outhouse: with

"hundreds of thousands of households in this country

living in housing conditions typically associated with

developing nations," like lack of indoor plumbing — a

problem in urban areas, but more so in rural areas. The

informational campaign is designed to shed light on the

impact of this element associated with substandard

housing.

In addition

to affordability and inventory, McAllister said that,

based on information from the 2016 American Community

Survey, nearly 30% of rural housing units have at least

one essential element that either doesn't function

properly or is just lacking. She also pointed out one of

the organization's campaigns, The Last Outhouse: with

"hundreds of thousands of households in this country

living in housing conditions typically associated with

developing nations," like lack of indoor plumbing — a

problem in urban areas, but more so in rural areas. The

informational campaign is designed to shed light on the

impact of this element associated with substandard

housing.

"One of my research colleagues, Lance George, calculates that there are about 150,000 rural housing units that don't have indoor plumbing," she said. "This is not something we think of as an issue existing in the 21st century, and certainly not in our country. Yet, it remains a housing problem that cannot be overlooked because it is not only a public health problem but an environmental problem [sewage]."

HAC's Rural Data Central

In addition to its research activities that help inform the HAC's policy work, the organization also functions as a community development financial institution (CDFI) and provides technical assistance and training. Its Rural Data Central provides national-, state-, and county-level information on housing, in addition to social and economic data on rural communities.

McAllister also pointed out other issues linked to

restrictive funding opportunities that impact rural

housing quality.

"Home improvement funding often comes with restrictions that lead to missed opportunities for improving quality," she said. "For example, a rural housing unit may qualify for the weatherization program that aims to provide heating and cooling modifications. But because the roof leaks, that unit becomes ineligible. In the end, these types of missed opportunities— as opposed to less restrictive holistic funding — also translate into negative health impacts in one way or another."

Who Takes Responsibility for Healthy Housing in Rural America?

In a July 2020 webinar reviewing healthy housing practices for rural developers, NCHH's Goodwin told the audience, "Anyone who touches housing has a role to play in ensuring housing quality, whether that be in touching legislative efforts, management areas, or for residents in their own settings."

NCHH executive director Reddy builds on her colleague's statement by suggesting that "anyone" also includes public health, medical, and housing experts. She said that although the language of the housing and health sectors might differ, both are referencing the same endpoint: the common goal of improved population health and well-being.

"We might be using different language to describe the work," Reddy said. "The public health community talks about interventions; housing professionals talk about home improvements, remodeling, remediations; and healthcare providers talk about improved health outcomes. We need all of these sectors to be at the same table working together to achieve the mutual goal and address the issues that are keeping our individual group efforts separate. We have evidence-based strategies that can be maximized if we work together."

Resources

Federal Agencies

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC)

Healthy Housing Reference Manual - Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD)

Multiple resources addressing rural housing issues - United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

Rural housing programs and opportunities

Other Organizations

- American Public Health Association

Policy Statement: Housing and Homelessness as a Public Health Issue - Housing Assistance Council (HAC)

2018 Rental Housing for a 21st Century Rural America: A Platform for Production - Meals on Wheels America

Effective Partnerships Between Community-Based Organizations and Healthcare: A Possible Path to Sustainability

Impact of Home Modifications and Repairs on Older Adults' Health and Well-Being - National Association for Area Agencies on Aging

(n4a)

The Role of Area Agencies on Aging in Home Modifications and Repairs

Case Study: Public Housing and Assisted Living Facilities, White River Area Agency on Aging, Batesville, Arkansas in Housing and Homelessness Services and Partnerships to Address a Growing Issue - National Center for Healthy Housing (NCHH)

Community Healthy Housing Assessment Data

Financing and Funding Resources

Housing Code and Regulation Resources

Technical Assistance and Coaching Resources

Case Studies and Technical Briefs - Rural Health Information Hub

Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit

Social Determinants of Health for Rural People Topic Guide