Feb 26, 2020

Making a Difference for Generations to Come: School-Based Oral Healthcare in Louisiana

"Over a

decade ago, we had a young patient who had 24 cavities

and told us even water hurt their mouth," Arbor

Health's Linda Matessino said. "That's just

heartbreaking, especially when you know that patient is

representative of many children and has a condition that

can be prevented. Oral health is just so incredibly

important for the overall health of the body. I knew we

could make a difference for our patients."

"Over a

decade ago, we had a young patient who had 24 cavities

and told us even water hurt their mouth," Arbor

Health's Linda Matessino said. "That's just

heartbreaking, especially when you know that patient is

representative of many children and has a condition that

can be prevented. Oral health is just so incredibly

important for the overall health of the body. I knew we

could make a difference for our patients."

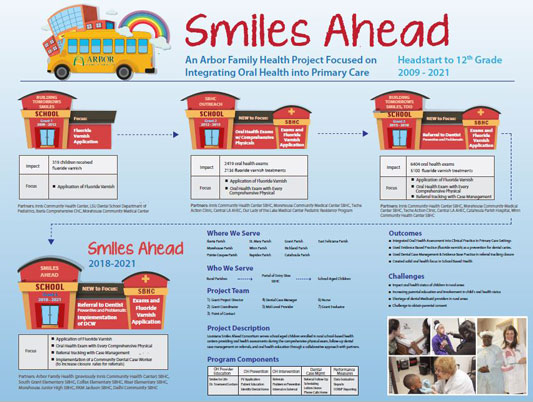

Matessino, referring to herself as a builder and a networker, said she saw the opportunity to improve oral health with the Rural Health Care Services Outreach Grant when she was a CEO for Arbor Family Health, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Louisiana. Now a four-time awardee, the organization continues to build its oral health services, both programmatically and geographically. Partnering with other Louisiana FQHCs and School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs), some consortium organizations are as far away as 200 miles from the primary grantee's site in Pointe Coupee Parish. In total, clinicians serving 12 SBHCs in nine parishes have received oral health assessment training and are able to provide fluoride varnish application and oral health education to children and their parents.

Matessino, now the organization's grants program director, explained that each grant award led to improved processes that could easily be disseminated to other organizations that were also committed to children's oral health. She was quick to add that focusing on children's oral healthcare now could minimize their dental problems as adults. For example, preventing the adult dental conditions that can only be resolved by tooth extraction or problems of jaw bone erosion that preclude proper-fitting dentures.

With Arbor Family Health's first grant, the target population was preschool children coming to the FQHC. Leveraging that initial funding, the organization hosted training events and created the program Building Tomorrow's Smiles. As the grant cycle ended in 2012, a larger issue emerged.

"We already had dental care in our FQHC model, but we still weren't reaching children like we wanted to," she said. "We realized that when a parent brings a child to the clinic, it's usually not for the preventive exam. Instead, it's for an acute problem and doing an oral health assessment on a sick child is not the focus of that visit. Additionally, our high no-show rate for well-infant and child check-ups also led to low intervention numbers."

Matessino explained that they were easily able to "self-correct" since the consortium organizations had already branched out into SBHCs, a care delivery model that would offer a better access portal to the target population. With a second grant award and several new partners from other parishes — including a collaboration with a nearby pediatric residency program — the Arbor Family Health's program expanded its outreach and provided oral health assessments for children 3 to 13 years old. Several thousand children received fluoride varnishes and several hundred dental referrals were made for abnormalities identified during the oral health assessment.

Throughout the work of the second grant, which concluded in 2015, Matessino said the consortium partners were dissatisfied with one specific outcome measure: completed referrals for dental care. Reviewing more evidence-based information, they determined dental case management might help address the problem. Again, with several new parish partners added as partners, Arbor Family Health applied for another grant and trained identified FQHC and SBHC staff members to provide case management. According to Matessino, as that grant cycle ended in 2018, the consortium partners felt their vision for a best practice in oral health was beginning to materialize when completed referrals to dental providers increased from a baseline of 14% to 64%.

Grant Results

2012-2015 results

- The actual number of varnish applications exceeded the initial estimate by nearly 900 children, or 171% of the target goal

- Oral health caries risk assessments totaled 2,273, or 182% of the original target estimates

- 14% of those provided with a dental referral completed the referral process

2015-2018 results

- Targeted all children enrolled in school-based health centers, age 3 to 19

- Dental case management staff trained

- 100% of providers trained in oral health assessments and fluoride varnish application through the American Academy of Pediatrics program Protecting All Children's Teeth

- Over 6,400 completed oral health assessments

- 5,100 applications of fluoride varnish

- 2,350 dental referrals, averaging a 64% completion rate, substantially above the baseline 14%

Matessino pointed out that with current funding from

their fourth grant, they are still hoping to gain an

improved dental referral rate in addition to further

program dissemination.

"We understand that it's unlikely to have 100% completion rate making sure all children referred to the dentist get to that appointment," she said. "So much of our case management effort goes into trying to engage parents through phone calls; tracking new numbers after discovering disconnected numbers; and knowing that when parents saw the clinic number, they either didn't answer because of concern that it was a billing call or blocked the call. So, we wondered if adding a community health worker (CHW), another evidence-based intervention with that trusted person in the community, could provide a different type of outreach. With our fourth grant award, we're bringing the established program to several new partners and we're implementing that CHW workflow as a pilot in one site. We're working on this. Pragmatically, it's tougher than we anticipated."

Keys to the Accomplishments

"Early on, one of the clinicians made clear to us an important motto that has influenced our approach: You can't take the mouth out of the body and hand it off to the specialist for care," Matessino said. "We knew that good oral healthcare had to start with primary care clinicians accepting their role in screening by doing oral health assessments, identifying potential pathology, generating dental referrals, and applying fluoride varnish as part of their routine work."

We knew that good oral healthcare had to start with primary care clinicians accepting their role in screening by doing oral health assessments, identifying potential pathology, generating dental referrals, and applying fluoride varnish as part of their routine work.

Matessino and her team also recognized the importance of program dissemination to other like-minded organizations in the geographically and culturally varied parishes of Louisiana. As the lead grantee, they created evidence-based and -informed tools and processes allowing flexible implementation at other sites. Several essential elements are:

- Clinician training using the American Academy of Pediatrics curriculum (no longer available online) and other supplemental presentations as needed to refresh oral health assessment skills

- Program-specific instruction for fluoride varnish application done by physicians, nurse practitioners, or nursing staff

- User-friendly data collection tools, such as specialized spreadsheets to track data

- Integration of oral health education for children and

parents as part of the oral health assessment

- Emphasizing the importance of keeping sugar off the teeth: for example, rinsing their mouth with water after drinking soda

- Training FQHC and SBHC staff members in case

management approaches, including:

- Parent engagement in oral healthcare

- Educating and connecting parents with dental appointment opportunities

- Grant funds paid for salaries, outreach activities, fluoride varnish, and toothbrushes

Matessino also

shared several guiding principles of the program. For

example, the need to approach the work knowing it would

be difficult, but understanding that doing nothing about

oral health was not an option. She said they also

acknowledged that the program's success would depend

operationally on the buy-in of the primary care

clinicians doing the oral health assessments in order to

make it more than the traditional collaboration with

dentists. With the recent addition of case management,

she said they've had to acknowledge that though the

"monumental" case management effort

is very difficult to measure, it can still help document

program success.

Matessino also

shared several guiding principles of the program. For

example, the need to approach the work knowing it would

be difficult, but understanding that doing nothing about

oral health was not an option. She said they also

acknowledged that the program's success would depend

operationally on the buy-in of the primary care

clinicians doing the oral health assessments in order to

make it more than the traditional collaboration with

dentists. With the recent addition of case management,

she said they've had to acknowledge that though the

"monumental" case management effort

is very difficult to measure, it can still help document

program success.

School-Based Oral Healthcare: A Clinician's Perspective

Latasha Johnigan is a family nurse practitioner and a clinical director at Arbor Family Health. Now with the organization for 10 years, she originally split her clinical time between the family medicine and school-based clinics. In those settings, she said she quickly realized her passion.

"I would see 25-year-old patients in the family medicine clinic and realize that the education I was giving them could have had more impact on them — and their parents — when they were age five," Johnigan said. "Parents and their children both can benefit from the same information."

Johnigan said at the first opportunity, she transitioned to full-time school-based practice where the oral health assessment was becoming a standard practice. She credits the specialized oral health training modules in helping her discern abnormal findings and in teaching the application of fluoride varnishes.

"The training fine-tuned what we should be looking for," she said. "There are subtle findings that are actually going to become acute problems if not dealt with in advance. For example, the physical findings of decay and plaque along with abscesses that, surprisingly, many times can be painless. Most primary care training focuses on examining the front of the teeth. All you need to do is spend a few more seconds looking at the back of the teeth and you can find even more early signs of preventable problems."

Johnigan said that with their grant activities over the past decade, multiple challenges associated with providing basic oral healthcare to school children have been overcome. For example, familiarizing the children and parents with the exam and bringing the dental professionals to the school using a mobile dental van, an intervention that eliminated the need for parents to identify a dental provider, take time away from work, or find transportation to get needed dental care. Additionally, Louisiana Medicaid, the insurer for many of her patients, now covers two cleanings a year, another bonus for the oral health of her patients.

"When I look back on our program's success, the biggest reward for me is seeing such a dramatic improvement in school absenteeism," she said, with school absenteeism being a common public health data point for assessing children's dental health needs.

Future Generations: Beneficiaries of Current Oral Health Interventions

Matessino said though learning never stops and quality improvement applies to this oral health program as it does to many others, the most important part of the program is acknowledging that because they've taken children through the early years of oral health, these same children have a better chance of becoming adults with healthier teeth — and hopefully becoming parents and grandparents of children with a routine of good oral health habits that are second nature.

My greatest hope resulting from this project is that our kids will grow up with better teeth and because they'll have better teeth, then their kids will have better teeth.

"My greatest hope resulting from this project is that our kids will grow up with better teeth and because they'll have better teeth, then their kids will have better teeth," she said. "This work hopefully impacts generations to come and maybe, just maybe, someday we'll be able to say that in rural areas we do have improved access and we don't have to live with rotten teeth or lost permanent teeth."

Matessino shared how the program's successes have motivated clinicians to continue to do the work of oral health assessments.

"Remember that young patient I told you about with 24 cavities and so much pain that water hurt?" she said. "We never see cases like that anymore. It's hard to show that with objective data, but our clinicians tell me they just don't see the bad teeth in the numbers like they used to. When I ask clinicians to raise their hands if they plan to stop their oral health assessments when grant support goes away, there's not a hand in the air. Fluoride varnish is cheap. New toothbrushes are cheap. Now that we've got a program that's working, they tell me they'll keep doing it as part of their routine care because they can tell it makes a difference."

And it's not just the clinicians who seem interested in the continued integration of oral healthcare into school-based care – it's also the children. Matessino shared a common conversation between child and clinician:

"Are you going to put that stuff on my teeth again this year?"

"Yes."

"Are you going to give me a new toothbrush?"

"Yes."

"Well…OK then."

Resources

American Academy of Pediatrics

American Dental Association

National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services

Rural Health Information Hub's oral health resources

- Oral Health Toolkit

- Community Health Workers Get Trained to Reduce Oral Health Disparities, The Rural Monitor, March 2017.

- Models and Innovations, Oral Health

Rural Health Research Gateway