Oct 14, 2020

One Health: Bringing Health to Humans, Animals, and the Environment

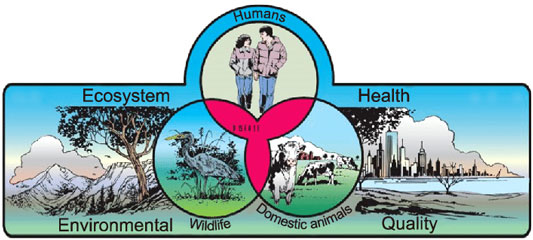

"One Health is the approach that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals, the health of plants, and the health of our shared environment," explained Dr. Casey Barton Behravesh, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) One Health Office located in the agency's National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases.

One Health experts suggest that understanding this inter-relationship between human, animal, plant, and environmental health is especially important for individuals and organizations associated with rural human health. Why? Because they are responsible for providing care for humans in an essentially One Health-intensive environment: 20% of the nation's population living in 90% of the country's landmass alongside one another, their pets, their livestock, and a huge variety of wildlife on or near cropland, ranchland, and government-protected environmental areas. One Health experts also provide this reminder about that list: each can function as an entry point for diseases that impact the rest.

One Health's Scope

One Health is not a new approach, but is an approach more recently put into action because, as highlighted by the CDC, "the movement of people, animals, and animal products has increased from international travel and trade. As a result, diseases can spread quickly across borders and around the globe."

The scope of One Health includes zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, food safety and security, vector-borne diseases that come from insect bites, environmental contamination, and other health threats shared by people, animals, and the environment.

Starting with diseases that have origins in animals,

Barton Behravesh further explained some of One Health's

efforts around zoonotic diseases, those that are spread

between animals and people.

"It's important to recognize that more than half of all known infectious diseases in people are zoonotic, meaning that they can come from an animal," Behravesh said. "It's equally important to recognize that three of every four newly emerging diseases, like COVID-19, also start off in an animal. That makes a One Health approach critically important."

Consider rabies.

"People tend to know about rabies because they know they're supposed to get their dogs and cats vaccinated for rabies," Barton Behravesh, a veterinarian and epidemiologist, said. "In our country, vaccinating dogs and cats for rabies has been very important in eliminating a strain of rabies we call canine-mediated, meaning it spreads from dogs. But rabies continues to be a huge problem around the rest of the world and an estimated 59,000 people, about half of which are children, die every year despite the fact it's a preventable public health issue."

Healthy Pets, Healthy People

Though pet owners will be the first to say no studies are needed to prove that pet ownership improves their health and well-being, much scientific evidence exists supporting those links. However, sometimes pets can transmit diseases to their owners and experts said awareness of pet-specific zoonotic diseases is important. Children less than 5, adults over 65, and people with weakened immune systems are at higher risk. Prevention basics include a focus on clean hands, clean pet equipment, clean pet living area, and regular veterinary care to keep pets healthy. Keep food and animals separate.

One example of zoonotic transmission is Toxoplasmosis, a disease caused by the parasite Toxoplasma. The parasite can infect cats — and cats can then pass the parasite to humans. If mothers-to-be acquire the parasite, birth defects can result. The CDC also advises that reptiles like snakes, lizards, and turtles as well as amphibians such as frogs and toads should not be kissed, snuggled, or held close to the face since they can sometimes carry Salmonella germs that can make people sick.

Experts also pointed out that the reverse situation can occur: pet owners can transmit illness to their pets. Though not yet fully understood, current information indicates that pets can catch COVID-19 from close contact with infected people, though there is a low risk of pets passing it to humans, according to the CDC.

One Health Collaboration in Action: HPAI

Dr. Jonathan Sleeman is Center Director at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) National Wildlife Health Center, a Science Center within the Department of the Interior (DOI). In a 2017 paper, Sleeman and his colleagues pointed out that, as mentioned by Barton Behravesh, about 70% of zoonotic diseases emerge from wildlife.

Think any kind of wildlife. Think wild waterfowl and HPAI, highly pathogenic avian influenza.

In 2014-2015, HPAI, a virus that infects wild birds, gained an entry point that impacted U.S. food production. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), over 200 Midwest commercial producer sites had infected turkeys and egg-laying chickens. Sleeman said the take-away from their 2017 paper is an understanding of the effectiveness of an interagency committee and One Health collaborative efforts during that HPAI outbreak.

"The steering committee was a good example of One Health in action," he said. "When HPAI first emerged, the initial reaction was to cull the wild birds and destroy wetland habitat around farms —which helps poultry farms, yet doesn't help the wildlife or the environment. But together, the CDC, the USDA, the DOI, and state agencies worked on the problem, including concerns about how further spread would impact human health as well as the food supply. The committee brought in additional stakeholders, like the poultry producers, hunters, environmentalists, and wildlife interest groups. Because of the steering committee leadership, there was an eventual win-win-win: for people, for animals, and for the environment."

One Health and the National Park Service

With many of its personnel living and working in rural areas, Sleeman said another DOI agency that should not have their One Health efforts overlooked is the National Park Service (NPS). NPS's activities range from disease surveillance to providing their managers and staff with "holistic, ecologically based science guidance for ecosystem, wildlife and visitor health," to visitor education in order to prevent acquiring diseases transmitted from either the environment or wildlife vectors.

Sleeman said he didn't recall that rural healthcare

organizations were specifically called to engage in the

HPAI efforts, but he did recall that many other rural

stakeholders were — and continue to be involved with One

Health issues.

"Because hunters and guides are out there in the field, they're critical members of teams that help access wildlife," he said. "The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also have a lot of people in the field working with local communities. These are the folks who know where the birds are. We also very much rely on the general public in rural areas to report unusual wildlife mortality events. Living in those areas allows an awareness of what is normal and abnormal regarding wildlife patterns, so they are tuned in and can report the unusual."

Current USGS Research Efforts

As a science agency, Sleeman said the USGS's mission is to provide information that contributes to environment and wildlife management, inherently based on One Health principles, as is evidenced by their research around HPAI.

"Wild birds carry HPAI and nobody wants those viruses to get into poultry barns or people, so preventing first entry is extremely important," Sleeman said. "Our primary focus was on better disinfection procedures and biosecurity procedures on farms, but our research has shifted. Now we're also focusing on using radar to track wild bird migration patterns to predict when these birds could be arriving close to poultry farms. This provides a forecasting tool for these producers who can, in turn, ramp up their biosecurity measures, start disinfecting their tractors, and start using the appropriate personal protection equipment, hopefully making these measures more effective."

Sleeman shared that rural individuals and organizations interested in more information and further education can connect with One Health activities like citizen science efforts or specific activities for youth.

Teaching One Health Concepts to Rural Healthcare Providers

Animals and the environment have significant impact on human health and human well-being. From human illness connected to wild animals — think HIV — or the bioterrorism threats with anthrax exposures nearly two decades ago. Recall anthrax: a deadly bacteria found in the soil which can affect both wildlife and domestic animals. With all these zoonoses, think about the awareness and education needed for rural providers.

Dr. Diane Rohlman, Endowed Chair in Rural Safety and Health at the University of Iowa College of Public Health, is course director of Agricultural Safety and Health: The Core Course, attended by professionals from throughout the country. She said the curriculum offers many attendees their first exposure to both the concepts of One Health and the collaborative processes required to manage issues associated with animal, human, and environmental health. For the university's dual degree veterinary/public health students who already have One Health integrated in their veterinary curriculum, the course often allows them more interaction with human health experts since many of the other attendees are medical professionals: nurses in multiple roles, from rural clinics to agricultural companies' occupational health departments; physicians from specialties ranging from emergency medicine to family medicine; pharmacists; first responders; and other public health students and veterinarians. For the medical professional course participants, the course also offers them a chance to connect with the animal health professional attendees and course presenters.

"Every one of these professionals has a role to play in rural health and safety," Rohlman said, emphasizing the many permutations of how farming, ranching, and rural manufacturing link to human health, animal health, and efforts around sustaining a healthy environment. "You just can't lose track of that fact. Especially with farming and ranching, the health of the animals is not separate from the health of the farmers and ranchers themselves as they work in occupations that depend on a healthy rural environment."

Rohlman said that for some of the participants, the class becomes a way to formally label these One Health efforts that already are naturally integrated into their professional work. She also noted that although there are many non-One Health issues covered in the course, even those issues benefit from a One Health collaborative approach, a point emphasized by the CDC's One Health.

"When we focus on One Health concepts during the course, that exposure builds participants' competence and confidence so that they can contribute to the issues they previously considered outside their wheelhouse," she said.

One Health: An Informal Rural Version?

Common rural scenarios: In a small town, a community member calls the mayor or another community leader about a raccoon that's just shown up during the day, staggering around the neighborhood, unusual since raccoons are nocturnal wildlife and don't stagger if they're well. A second scenario: A family veterinarian tells a farm or ranch family member they'd better check with their own healthcare provider after diagnosing livestock with a potential animal-to-human disease. Meanwhile, the vet reports to county or state agencies. And yet a third scenario: The area's farmers and ranchers compare notes, realizing that they've all reported finding deer in the last 48 hours, lying dead at a watering source, unrepresentative of a natural death.

Though lacking specifically labeled efforts, these scenarios share much of what represents One Health actions/reactions in rural life: inherent knowledge combined with informal networks around a common concern for potential human-animal-environment disease transmission.

For rural organizations interested in learning more about One Health, the CDC's Zoonoses & One Health Updates (ZOHU) calls provide not only information, but free continuing education. The CDC is also leading efforts to educate rural youth in a collaborative effort with USDA Cooperative Extension Service and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, jointly providing the Influenza and Zoonoses Education among Youth in Agriculture program.

Educating Public Health and Medical Workforce

In 2009, the National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-borne, and Enteric Diseases created the CDC's One Health Office "as a point of contact for external animal health organizations and to maximize external funding opportunities." Now, the One Health Office also supports public health research and facilitates data and information exchange done by researchers across many disciplines and sectors. One Health Office Director Barton Behravesh shared more about the Office's work.

"In order to protect the health of people and animals living in shared environments, we work to bring awareness about One Health in the United States and worldwide and help support partners in implementing a One Health approach to their work," Barton Behravesh said. "In addition to our work with partners like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Department of the Interior, state and local public health and animal health agencies, we also work with global partners like the World Health Organization and the World Organisation for Animal Health."

In the past several years, other organizations are also focusing on One Health. For example, in 2017, the American Public Health Association (APHA) published a policy paper featuring the One Health approach around zoonotic disease, food safety and security, and antimicrobial resistance — the issue experts said was one of the earliest and perhaps most uniting — as an approach addressing the same priority public health issues that concern their organization. As has also been suggested by many disaster preparedness experts, the APHA pointed out that any of these issues "may cause health emergencies or persistent public health burdens." These were predictive statements, considering three years later the zoonotic disease COVID-19 has emerged as an emergency and public health burden that has uniquely impacted rural America. As of 2018, APHA has recommended the education around the One Health approach be considered mandatory for advanced degree programs.

In addition to the CDC and the APHA, U.S.-based human and animal health organizations have been working collaboratively in their efforts to embrace the One Health approach. In 2007, the American Medical Association passed a resolution accepting the One Health partnership offered them by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). In 2008, a task force led by the AVMA on a "new professional imperative" included many experts, including the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).

AAMC President Emeritus, Dr. Darrell Kirch, shared his personal and professional goals related to his work on that task force. Kirch had been dean of the Medical College of Georgia — a state where 75% of counties are rural — and later the CEO of Penn State Hershey Medical Center and dean at Penn State College of Medicine, a part of a "very old and established land grant college." In these positions, he said he'd become more fully aware not only of the benefits that emerged from joint work between a strong agriculture and animal medicine program when linked to human medicine programs, but how rural human health interests intersect with One Health efforts. When he became AAMC president, that past experience guided his task force work.

"Since we're all occupying a single or one health ecosystem globally, it's more important than ever that we take an interprofessional health perspective," Kirch said. "We've known for centuries about animal-borne diseases in which animals serve as the vector. Say "bubonic plague" and there's not much response. Despite knowing about swine flu and the avian flu, COVID is what really got the public's attention. I don't think that human-animal connection has felt as real to the American public as it does now when COVID-19 hit us."

Though his AAMC leadership concluded in 2019, there are signs that medical schools are continuing his work to adopt One Health concepts: A recent AAMC news story featured medical students interfacing with zoo veterinarians, pediatricians studying water quality, and student lectures on how environmental change that impacts polar bears is also impacting tribal communities.

Further indication of the increasing reach of One Health was noted by the National Academy of Medicine. In its 2018 discussion paper, authors listed approximately 45 U.S. One Health degree programs associated with health-related professions.

EIS: The CDC's Own Intelligence Service

As Barton Behravesh reviewed many of CDC's One Health activities, she also shared information about the CDC's own Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) training program. A competitive program for degreed professionals including physicians, nurses, veterinarians, and health scientists, it provides specialized training and mentoring in the application of epidemiology to public health problems.

"In that program, you're working on real-world public health issues and getting training that allows you to build your career in public health," Barton Behravesh said. "Some of the EIS officers work at the federal level at CDC headquarters to tackle public health issues across the country or the world, while others are assigned to state and local health departments, including those in rural areas.

"Growing up on a dairy goat ranch in rural Texas, I was active in 4-H and FFA and decided I wanted to become a veterinarian. During my college education, I became interested in diseases that spread between animals and people. Eventually, I was able to participate in EIS where I was in class with physicians, other veterinarians, scientists, and nurses. It is really wonderful to have those different disciplines train together and build an important network of colleagues. I have been working on One Health issues my entire CDC career, and it's been a great way to impact health in every sense of its definition."