Cancer Prevention and Treatment in Rural Areas

Rural Americans face many unique challenges across the cancer control continuum, from exposure and diagnosis through treatment and survivorship. Rates of cancer and stage of diagnosis can also vary widely in rural areas depending on environmental impacts, population demographics, availability of screening, and access to culturally informed treatment options. While there are comparable cancer incidence rates between rural and urban populations in the U.S., the approximately 60 million rural residents face higher cancer mortality rates. Cancer prevalence, or the number of living people who have ever been diagnosed with cancer, is slightly higher in rural populations compared to urban populations.

| Rural | Urban | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 6.9% | 6.1% |

| Source: Health, United States, 2019. Table 13: Respondent-reported prevalence of heart disease, cancer, and stroke among adults aged 18 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, average annual, selected years 1997–1998 through 2017-2018 | ||

Rural populations more frequently have cancer types related to modifiable behaviors, such as tobacco use, compared to urban populations. The Rural-Urban Disparities in Cancer map story, from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), provides more information on rural-urban differences in cancer incidence and mortality. Additionally, NCI's state cancer profiles provide county-level data on cancer incidence, mortality, and demographics, and other cancer screening and risk factor information.

Lowering the cancer burden in rural areas is important for improving rural health. This guide will discuss the cancer-related risks and barriers faced by rural Americans, specific rural geographic areas, and racial and ethnic groups that experience higher rates of cancer. It will also provide strategies for reducing rural cancer risk and overcoming barriers to rural cancer screening and treatment, how policymakers can support local rural cancer prevention and control efforts, and how government agencies are supporting rural cancer control initiatives and research.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What contributes to higher incidence rates of cancer in rural areas and what can be done to reduce the risk?

- What are evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of cancer?

- What are evidence-based recommendations for cancer screening?

- How do rural areas differ from urban areas in their use of cancer screening?

- What are evidence-based strategies and approaches for increasing screening uptake in community and clinical settings?

- How do rural areas differ from urban in access to and quality of cancer treatment?

- What approaches have been successful in addressing distance-related barriers to care in rural areas?

- How do rural areas differ from urban in cancer survivorship?

- Are particular parts of the country more prone to cancer?

- How can policymakers support cancer prevention and control efforts in rural areas?

- What are federal agencies doing to address rural cancer control?

What contributes to higher incidence rates of cancer in rural areas and what can be done to reduce the risk?

The social determinants of health (SDOH), including economic stability, education, social and community context, access to healthcare, and neighborhood factors, can affect cancer incidence rates in rural areas. Several lifestyle factors such as tobacco use and diet can also put individuals at increased risk for developing cancer.

In general, rural populations are more likely to live in poverty and have lower educational attainment. The 2013 Annals of Behavioral Medicine article, Spatial Disparities in the Distribution of Parks and Green Spaces in the USA, found that rural populations are more likely to live in neighborhoods with less access to parks and green spaces that can encourage cancer prevention activities such as exercise. A 2018 Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention article, Rural-Urban Differences in Cancer Incidence and Trends in the United States, found that a third of rural cancer cases are diagnosed in counties with greater than 20% of the population living in poverty compared to 11% of urban cancer cases. The 2018 article reports incidence rates for tobacco-associated, human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated, lung and bronchus, and colorectal cancers were higher for rural counties with 20% or more of the population living in poverty than for similarly impoverished urban counties.

Environmental Exposures

Environmental exposures, such as poor water quality and indoor or outdoor air quality, can cause an increased risk for cancer. A 2017 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) article, Rural and Urban Differences in Air Quality, 2008-2012, and Community Drinking Water Quality, 2010-2015 — United States, reports that rural populations have higher exposure to poorer quality water and less exposure to poor outdoor air quality. However, in a 2018 Journal of Public Health Management and Practice article, Predictors and Spatial Variation of Radon Testing in Illinois, 2005-2012, rural populations in Illinois were found to have lower rates of testing their homes for radon, an odorless radioactive gas, the second leading cause of lung cancer. Radon can enter a home through the cracks in the foundation of a house, through holes or openings in a basement, and can be found in drinking water.

In addition, rural households are more likely to drink well water, which is more likely to contain radon, arsenic, and other carcinogens compared to treated and tested municipal water. Rural populations in agricultural areas may also experience increased exposure to pesticides that may put them at greater risk for some types of cancer.

To learn more about water quality and air quality in rural areas, see What types of environmental hazards do rural communities face that endanger the health of their residents? on the Social Determinants of Health for Rural People topic guide. To find state and county-level data on environmental exposures, see the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network.

Tobacco Use

According to the NCI, tobacco use, including both smoked and smokeless products, is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality. The American Cancer Society estimates that tobacco use is the cause for 30% of all cancer deaths. It has been directly linked to many cancers, including but not limited to:

- Lung

- Oral

- Esophageal

- Bladder

- Kidney

- Colorectal

- Pancreatic

- Cervical

- Acute myeloid leukemia

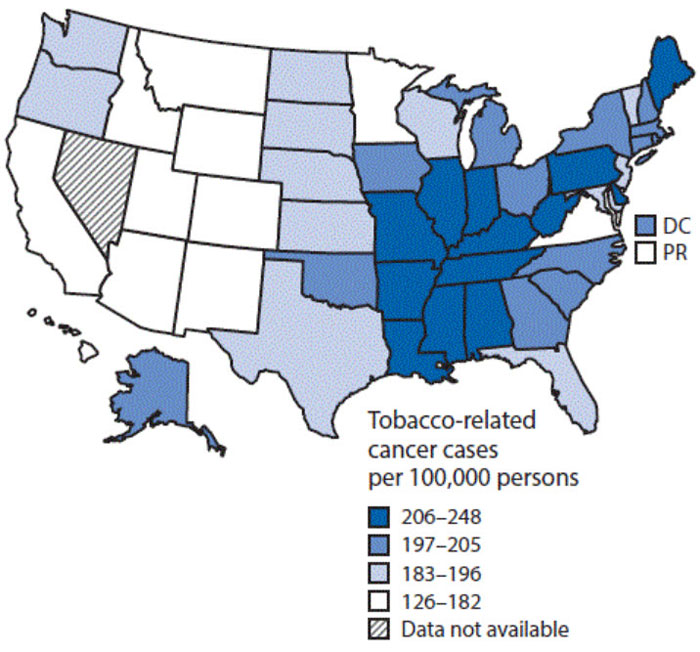

A 2016 MMWR article, Vital Signs: Disparities in Tobacco-Related Cancer Incidence and Mortality — United States, 2004–2013, found the burden of tobacco-related cancers is not evenly distributed throughout the U.S., but is higher in the South and Midwest.

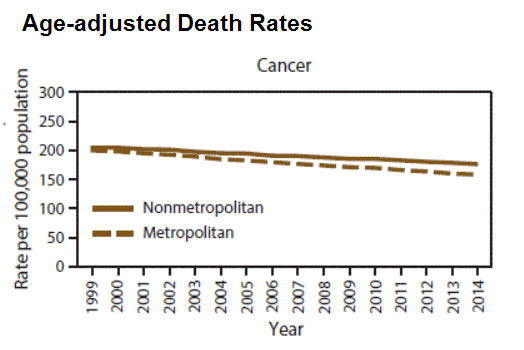

Surveillance for Cancers Associated with Tobacco Use — United States, 2010–2014, a 2018 MMWR article, showed tobacco-related cancer rates were higher in nonmetropolitan areas compared to metropolitan areas.

| All | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 61.3 | 72.7 | 52.7 |

| Metropolitan | 59.8 | 70.4 | 51.9 |

| Nonmetro | 69.4 | 84.9 | 57.0 |

| Source: Surveillance for Cancers Associated with Tobacco Use — United States, 2010–2014, Table 1, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 1-42, November 2018 | |||

At all ages, those in rural areas are more likely to be exposed to tobacco use. That same 2018 MMWR article reports that adults in rural regions are more likely to smoke a pack of cigarettes a day, or more, compared to adults in urban areas. Teenagers in rural regions are more likely to smoke and initiate smoking earlier in life than their urban peers. Even among children, those living in rural households are exposed to secondhand smoke more frequently than children in urban households, 35% compared to 24% respectively.

The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, a 2014 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) report, provides more information about the history of tobacco-causing cancers and the mechanisms connecting tobacco use to cancer.

In 2020, 70% of adults who smoke reported wanting to quit, according to the Surgeon General. Despite the desire to quit, rural adults may face more barriers to accessing smoking cessation programs compared to urban adults. In addition, small towns in rural regions have been less likely to adopt and implement local smoke-free policies. NCI's Geographic Information Science (GIS) Portal for Cancer Research tool, Tobacco Policy Viewer, offers state, county, or city level data on laws requiring 100% smoke-free workplaces, restaurants, and bars from 1990 to through 2020. NCI provides models, resources, and information on state and local ordinances and policies to reduce tobacco for policymakers and stakeholders. To reduce the burden of tobacco-associated cancers, concurrent smoking cessation efforts must occur in both the clinic and the community.

For additional examples of successful programs addressing tobacco use, see Rural Health Models and Innovations by Topic: Tobacco use.

Sun Protection

Excessive exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation ages and damages skin, which increases the risk of developing many types of skin cancers. People of all ages can reduce their risk of developing skin cancer by reducing direct exposure to sunlight and UV radiation by:

- Applying sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher and reapplying every 2 hours

- Staying in the shade

- Avoiding the outdoors or sun exposure when UV rays are the strongest, typically during the middle of the day

- Wearing protective clothing, including hats and sunglasses that filter UV light

- Avoid indoor tanning beds

These recommendations are especially critical for the health of farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural or construction workers who spend a large portion of their workday outside and in direct exposure to sunlight and UV radiation.

Non-melanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer in the U.S. but is rarely fatal. NCI's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) annually reports on cancer statistics. NCI SEER incidence data shows the rate of melanoma skin cancer continues to rise each year and five-year relative survival remains above 90%. However, individuals diagnosed with late-stage cancer with distant spread, or cancer that has spread to distant parts of the body, have a five-year relative survival rate of only 34.6% according to NCI SEER data. This statistic reaffirms the importance of early skin cancer screening, detection, and prevention activities. In rural regions, primary care providers are essential for detecting potential skin cancers, but individuals, especially those who work outdoors, can help their doctors identify early skin cancers by scanning their own skin for warning signs.

Healthy Food

Individuals with healthier diets, including higher fruit and vegetable intake and less red meat consumption, are less likely to develop cancer. While researchers have concluded that a healthy diet and consuming certain foods are associated with lower cancer risk, the causal connection is not clearly established and is less well understood. A healthy diet is critical to overall wellness and for preventing many chronic diseases, including cancer. Rural populations are less likely to maintain healthy eating habits, in part because they may have less access to healthy foods. For more information on access to healthy foods in rural areas, see the Rural Hunger and Access to Health Food topic guide.

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption has been shown to increase the risk for the following cancer types:

- Head and neck

- Esophageal

- Breast

- Liver

- Colorectal

- Stomach

- Laryngeal

In 2023, lifetime alcohol consumption for people aged 21 or older in nonmetropolitan areas was 87.0%, slightly higher than their counterparts in small metropolitan areas (86.1%) and large metropolitan areas (86.2%). Lifetime alcohol use for individuals aged 12 to 20 was 33.7% for nonmetro areas compared to 31.6% for their counterparts in large metro areas.

| Nonmetro | Small metro | Large metro | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime alcohol use for people aged 12 to 20 | 33.7% | 35.4% | 31.6% |

| Lifetime alcohol use for people aged 21 or older | 87.0% | 86.1% | 86.2% |

| Source: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA), Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. | |||

The 2014 Update of the Rural-Urban Chartbook reports that in all regions except the South, both male and female rural adults aged 18 to 49 had higher rates of alcohol consumption consisting of five or more drinks in one day in the last year than did their urban peers. A 2017 study in the Journal of Rural Mental Health, Correlates of Risky Alcohol Use among Women from Appalachian Ohio, found alcohol consumption is strongly linked to poor economic conditions and rural residents who are impacted by hard economic downturns face greater risks of alcohol abuse. For more information and resources on alcohol use in rural areas, see the Substance Use and Misuse in Rural Areas topic guide.

To prevent alcohol-caused cancers, rural communities may want to address alcohol consumption behavior. The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) is an independent panel of public health prevention experts that provide evidence-based recommendations and guidance on community-level health promotion and disease prevention interventions. CPSTF recommends strategies such as setting limits on the days and/or hours of alcohol sale and increasing alcohol taxes, which vary widely across the country and have been shown to effectively reduce alcohol consumption. The Rural Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Toolkit offers more information and ideas for implementing policies to reduce alcohol consumption.

Physical Activity

Physical activity is an essential component of a healthy life and can also help prevent cancer. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report recommends adults engage in moderate-intensity physical activity for a minimum of 150 to 300 minutes each week, or 75 to 100 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity that is spread throughout the week; as well as muscle strengthening exercises on at least two days of the week. The report also includes specific physical activity recommendations for youth, women who are pregnant or postpartum, older adults, and individuals with chronic conditions. In addition, the report recommends adults limit sedentary time, such as excessive sitting or inactivity.

Association Between Physical Activity and Mortality Among Breast Cancer and Colorectal Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, a 2014 Annals of Oncology article, found physical activity before or after a cancer diagnosis was associated with a lower mortality risk for breast and colorectal cancer survivors. Most adults in America do not meet the recommended physical activity guidelines. A 2019 MMWR article, Trends in Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines Among Urban and Rural Dwelling Adults — United States, 2008–2017, found that rural adults lag slightly behind urban adults in meeting physical activity guidelines. For examples of successful, evidenced-based rural program examples related to physical activity, see Rural Health Models and Innovations by Topic: Physical activity.

Vaccinations – HPV and Hepatitis B

According to the NCI, long-lasting and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) strains are the cause for most penile, vulval, vaginal, anal, mouth, and throat cancers, and the cause for virtually all cervical cancers. A 2014 Sexually Transmitted Diseases article, The Estimated Lifetime Probability of Acquiring Human Papillomavirus in the United States, estimated the lifetime probability of adults in the U.S. acquiring HPV by the age of 45 at 80%. A 2018 Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention article, Rural-Urban Differences in Cancer Incidence and Trends in the United States, found HPV-associated cancer rates were consistently higher in rural communities compared to urban communities and have increased in recent years.

Fortunately, there is a vaccine that can help prevent HPV from causing cancer. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is a panel of medical and public health experts who provide guidance to the CDC on the use of vaccines, including HPV vaccines. ACIP recommends the HPV vaccine for all children aged 11-12. A 2018 MMWR article, Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19–35 Months — United States, 2017, found vaccination rates in rural areas are lower for children and adolescents. Factors Associated with Not Receiving HPV Vaccine Among Adolescents by Metropolitan Statistical Area Status, United States, National Immunization Survey–Teen, 2016–2017, a 2020 Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics article, found that 45.4% of teens aged 13 to 17 living in rural areas had not received the HPV vaccine compared to 32% of their urban counterparts. The 2019 Implementation Science article, A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Trial Designed to Improve Completion of HPV Vaccine Series and Reduce Missed Opportunities to Vaccinate in Rural Primary Care Practices, identifies many challenges related to HPV vaccination in rural areas including:

- Access to healthcare and preventive services

- Lower socioeconomic state

- Health literacy

- Religious and spiritual beliefs

- Less parental engagement and communication with healthcare providers

The Rural Monitor article Effective Communication and Consistency in Increasing Rural Vaccination Rates highlights the success public health practitioners in Louisiana and Kentucky had in increasing vaccination rates in rural communities using clear, consistent communication strategies, and leveraging local clinics, schools, and faith-based organizations as critical assets. The 2019 Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics article, Policy Opportunities to Increase HPV Vaccination in Rural Communities, shares more information on policies to improve HPV vaccination in rural areas.

Another vaccine that can help prevent cancer is the hepatitis B vaccine. Hepatitis B is a serious disease that can lead to liver cancer. The ACIP recommends the hepatitis B vaccine for all newborns in the U.S. within 24 hours of birth and children and adolescents less than 19 years old who have not been previously vaccinated. A 2018 MMWR article, Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, provides additional recommendations for hepatitis B vaccination for adults, including people born before 1980 and people who have immigrated to the U.S. who may not have been vaccinated for the hepatitis B virus.

What are evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of cancer?

Many organizations provide guidance and recommendations for cancer prevention behavior and services, which apply to both rural and urban communities. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent panel consisting of experts in prevention, evidenced-based medicine, and primary care who provide recommendations on clinical preventive services. USPSTF recommendations on preventive health activities and programs receive a grade A, B, C, D, or I statement that is paired with clinical practice suggestions. Grade A and B recommendations provide information regarding the age and risk characteristics for which someone may be recommended for a given service, as well as how often the service should be provided. The USPSTF currently recommends the following cancer-relevant preventive measures with an A or B grade:

- Chemoprevention for women at increased risk for breast cancer

- Genetic testing and counseling for women with a family history of breast or some gynecologic cancers

- Hepatitis C screening

- Screening and counseling for unhealthy alcohol use

- Skin cancer prevention for children, adolescents, and young adults

- Smoking cessation in adults

- Tobacco prevention and cessation in children and adolescents

The American Cancer Society also provides evidence-based guidelines on diet and physical activity for cancer prevention, as does the American Institute for Cancer Research.

For more ideas and resources on prevention policies to reduce alcohol consumption, see prevention policies in the Rural Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Toolkit.

What are evidence-based recommendations for cancer screening?

USPSTF also provides recommendations for cancer screenings. Currently, USPSTF gives a grade A or B for breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer screening. The details of each A or B cancer screening are detailed in the table below:

| Age and Other Criteria | Frequency | Screening Method | USPSTF Grade | Release Date of Latest Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | ||||

| Women, age 40-74 | Biennial | Mammography | B | April 2024 |

| Cervical Cancer | ||||

| Age 21-29 | Every 3 years | Pap smear | A | August 2018 |

| Age 30-65 | Every 3 years | Pap smear

USPSTF Grade: A Release date of last recommendation: August 2018 |

||

| Every 5 years | HPV testing

USPSTF Grade: A Release date of last recommendation: August 2018 |

|||

| Every 5 years | Pap smear + HPV testing

USPSTF Grade: A Release date of last recommendation: August 2018 |

|||

| Colorectal Cancer | ||||

| Age 45-75 | Annually | Stool-based tests | A for ages 50-74 and B for ages 45-49 | May 2021 |

| Every 5 years | Computed tomography colonography | |||

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | ||||

| Every 10 years | Colonoscopy | |||

| Lung Cancer | ||||

| Age 50-80 with a 20 pack-year smoking history and are a current smoker or quit within the past 15 years | Annually | Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) | B | March 2021 |

How do rural areas differ from urban areas in their use of cancer screening?

Colorectal cancer

Age-appropriate colorectal cancer (CRC) screening for adults is less commonly used among rural residents than urban residents, and lower still among those in remote rural areas. According to a 2012 Cancer Medicine article, Urban–Rural Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening: Cross-Sectional Analysis of 1998–2005 Data from the Centers for Disease Control's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study, the type of screening test used between rural and urban residents differs. Rural residents may be less likely than urban residents to receive an invasive screening method, like flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, but more likely to opt for non-invasive methods that can usually be done at home such as fecal occult blood test (FOBT). According to the 2020 American Journal of Surgery article, Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Mortality for Rural Populations in the United States: Does Screening Matter?, differences in access to CRC screening methods between rural and urban populations does not completely account for differences in mortality.

A 2019 Rural and Remote Health article, Barriers of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Rural USA: A Systematic Review, determined a number of barriers to CRC screening shared between rural and urban patients, including:

- Cost of screening procedures and lack of insurance coverage

- Lack of time

- Embarrassment or discomfort

- Fear of the test

- Fear of finding cancer or burdening family members

- Lack of knowledge or other misconceptions

- Inadequate supply of specialists and subspecialists

- Distrust of the healthcare system

- No reminder system for patients

However, there are also some potentially rural-specific barriers identified:

- Lack of prevention attitude

- Lack of privacy due to knowing healthcare providers and screening staff

- Distances to travel for screening

- Transportation issues

Rural patients may also be less likely to go to the doctor until they feel sick or notice symptoms. Contrasts in Rural and Urban Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening, an article from the American Journal of Health Behavior, found rural patients were more likely than urban patients to believe it was helpful to find CRC early, but were less likely to receive screening recommendations or FOBT information from their healthcare provider, or to have completed an FOBT.

A 2017 Rural Monitor article, "Doing Something Exceptional": Rural Communities and Colorectal Cancer Screening, describes the impact preventive screening can have on outcomes for this particular type of cancer and highlights two rural programs that developed successful colorectal cancer screening programs.

Breast cancer

A 2012 Rural and Remote Health article, Effect of Rurality on Screening for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, found that women in rural regions were less likely to have ever had a mammogram and less likely to have had a mammogram in the last two years when compared to other geographic regions in the U.S. US Urban–Rural Disparities in Breast Cancer-Screening Practices at the National, Regional, and State Level, 2012–2016, a 2019 Cancer Causes & Control article, examined data from the 2012, 2014, and 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems (BRFSS) surveys to determine disparities in breast cancer screening among rural and urban women. The 2019 article found that disparities in screening do exist for women living in rural areas at the state, regional, and national levels, but that the gap is narrowing. The article reported that barriers to mammography continue to differentially impact rural women.

Lung cancer

Lung cancer screening has only been recommended by the USPSTF since 2013. Population-based estimates of screening have shown that screening uptake has increased but has been relatively low. A March 2021 Journal of Rural Health article, Low-Dose CT Lung Cancer Screening Uptake: A Rural–Urban Comparison, studied 2018 and 2019 BRFSS data, including the optional Lung Cancer Screening Module that was used by 8 states in 2018 and 18 states in 2019, and found no significant differences in LDCT uptake between rural and urban populations. Challenges and Opportunities for Lung Cancer Screening in Rural America, a 2019 article from the Journal of American College of Radiology, found variation across U.S. census regions between the population eligible for LDCT and the percent of the eligible population receiving LDCT screening in the past year. The 2019 article also highlights provider communication as a key challenge impacting LDCT screening in rural populations. A 2018 Preventing Chronic Disease article, Geographic Availability of Low-Dose Computed Tomography for Lung Cancer Screening in the United States, 2017, offers maps and state-level data tables outlining the geographic availability of LDCT. The 2018 article shares that the number of designated LDCT centers has increased more than 8 times since 2014 but that rural and urban disparities in accessing these centers still is evident.

Cervical cancer

A 2020 Journal of the National Medical Association article, A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities, reports that women living in rural have lower levels of cervical cancer screening and poorer outcomes. A 2017 MMWR article, Cancer Screening Test Use — United States, 2015, reports that the overall trend for cervical cancer screening use declined largely between 2000 and 2015 due to socioeconomic factors as well as those related to healthcare access. Community-Based Screening for Cervical Cancer: A Feasibility Study of Rural Appalachian Women, a 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases article, found rural Appalachian women reported greater comfort levels with collecting a specimen for HPV testing in the privacy of their own home compared to receiving a pap smear in a clinical setting.

What are evidence-based strategies and approaches for increasing screening uptake in community and clinical settings?

The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) assesses community-based interventions and programming around preventive services related to cancer screening. Cancer screening interventions are categorized as not recommended, insufficient evidence to recommend, or strongly recommended based on a review of the evidence, supporting materials, and findings. CPSTF strongly recommends the use of multicomponent interventions and interventions that engage community health workers (CHWs) to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. To learn about additional strategies that are recommended for client- and provider-oriented interventions to increase cancer screening, see the Community Guide's findings for cancer prevention and control.

NCI's Evidence-Based Cancer Control Program (EBCCP) is a searchable database of evidence-based interventions and cancer control programs that includes information on cancer screening and other topics along the cancer continuum. EBCCP can be searched by program area, population, delivery location, and community type, including rural areas.

The Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network (CPCRN) is a CDC-funded network of academic institutions and other partners focused on addressing cancer among all populations through community-based, participatory cancer research. CPCRN offers a training resource guide, Putting Public Health Evidence in Action, to help public health practitioners and program planners with identifying, selecting, implementing, and evaluating community health interventions.

Many states, localities, and health systems have patient navigation programs that work to educate patients on appropriate screening guidelines and help them understand their insurance coverage options. Successful patient navigation programs have found ways to remove potential barriers to screening, such as providing funds to cover transportation or childcare expenses so a patient can access a screening service. CDC provides a patient navigation overview, including information on creating and supporting patient navigation programs and providing examples of successful programs. Other programs and health systems have worked to improve access to cancer screening in communities and clinical settings by utilizing interpreters and culturally competent staff to address screening hesitancy. Some rural communities have successfully leveraged local assets, such as faith-based organizations and community health workers, to adapt evidence-based programs to meet the specific needs of their rural residents such as the Witness Project, the Robeson County Outreach Screening and Education (ROSE) Project, or the Community Cancer Screening Program (CCSP).

How do rural areas differ from urban in access to and quality of cancer treatment?

Rural cancer patients may experience more barriers to accessing cancer care services compared to their urban counterparts that include:

Travel distance to care

According to a 2021 Journal of Oncology Practice article, 2021 Snapshot: State of the Oncology Workforce in America, only 11.2% of oncologists practice in rural areas. A 2017 Cancer article, Population-Based Geographic Access to Parent and Satellite National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Facilities, found that 14% of the U.S. population lived more than 180 minutes in travel time from a NCI parent or satellite facility, and that most of this group was comprised of rural and tribal residents living in isolated areas.

Trends in Cancer Treatment Service Availability Across Critical Access Hospitals and Prospective Payment System Hospitals, a 2021 article in Medical Care, analyzed the availability of cancer treatments in Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and prospective payment system hospitals and found CAHs offered fewer options for cancer treatments and that their clinical service capability declined over time.

Transportation issues

According to 2023 American Community Survey 1-Year data on selected housing characteristics, from the U.S. Census Bureau, 8.4% of U.S. households do not have access to a vehicle. Rural residents without cars are highly dependent on public or alternative transportation. According to America at a Glance: 5310 & 5311 Transportation Funding in Rural Counties, a 2021 publication from the University of Montana Rural Institute for Inclusive Communities, fewer than half of all rural counties receive funding from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Enhanced Mobility of Seniors & Individuals with Disabilities – Section 5310 and/or the Formula Grants for Rural Areas – 5311. The FTA grant programs support transportation for people with disabilities, seniors, and rural areas with populations less than 50,000. Rural cancer patients who are unable to drive; do not have friends, family, or other relationships to help provide transportation assistance; and are unable to access social services may be unable or less likely to receive cancer treatment.

Financial costs and support

As the prevalence of cancer increases, so does the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis. Newer treatments can be more expensive, and many survivors find themselves living with cancer as a chronic condition. Rural cancer patients may experience higher financial burden as they are more likely to be underinsured or uninsured, live below the poverty level, and lack access to quality healthcare which may lead to more financial challenges in seeking needed care.

Identifying Cancer Patients Who Alter Care or Lifestyle Due to Treatment-Related Financial Distress, a 2016 Psycho-Oncology article, reports individuals living with cancer may try to cut costs by taking actions that impact their health and treatment plan such as delaying treatment, not filling a prescription medication, or taking less medication than prescribed. Physicians and other members of the healthcare team should initiate conversations with patients related to the costs of cancer treatment. Patients can be connected with patient navigators or social workers to help them with the financial challenges that come with a cancer diagnosis. Patient navigators can help rural cancer patients deal with issues related to securing and navigating health insurance and can help supplement costs regarding treatment-related travel.

Poorer access to clinical trials

Increased access to, and enrollment in, clinical trials could help address disparities in cancer outcomes among rural patients. However, according to a JCO Oncology Practice 2020 article Closing the Rural Cancer Care Gap: Three Institutional Approaches, rural patients experience barriers to participation in clinical trials. Patients located in areas with higher mean incomes, employment rates, greater numbers of American College of Surgeons-approved cancer programs, cancer specialists, and physicians overall were more likely to be enrolled in clinical trials. A 2018 Oncologist article, At What Cost to Clinical Trial Enrollment? A Retrospective Study of Patient Travel Burden in Cancer Clinical Trials, examined the travel burden on patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials and found the distance traveled per clinic visit was highest among patients from low-income areas. The 2018 article reports 25% of patients enrolled in clinical trials sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) traveled 100 miles or more each way per clinic visit.

Even in cases where traveling long distances is not required, some patients may decline participating in a cancer clinical trial because the requirements associated with enrollment are seen as a deterrent. In these cases, telemedicine can be useful in assessing trial eligibility and obtaining consent to participate. In addition to increasing access to cancer clinical trials, telemedicine can be used in trial follow-up, including symptom assessment and management. Challenges of Rural Cancer Care in the United States, a 2014 Oncology (Williston Park) article, discusses the importance of dedicated research staff to help recruit and enroll patients in clinical trials. Other challenges small rural cancer centers can encounter is not having adequate patient volumes to support clinical trial research and fewer patients completing all of the clinical trial phases. In an attempt to address this gap in care, the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) aims to bring clinical trials to communities across the country in order to ensure research is reflective of the national population and addresses geographic disparities in cancer care delivery. Currently, NCORP is comprised of 7 research bases and 46 community sites.

Poorer access to palliative care and hospice services

Palliative care is an essential component in the comprehensive treatment of cancer patients experiencing adverse effects of the disease itself or side effects of treatment. Unfortunately, the availability of palliative care services may be limited in rural counties. A 2020 Journal of Geriatric Oncology article, Barriers to Palliative and Hospice Care Utilization in Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review, found that rural residents were less likely to use hospice and palliative care services due to a lack of access and having to travel longer distances to receive services, which adds another layer of challenges for rural cancer patients who do not have the support they need to remain home at the end of life.

The Rural Monitor article Community-based Palliative Care: Scaling Access for Rural Populations shares the important role palliative care plays in the lives of rural residents and discusses challenges related to access when providing palliative care in rural areas. Forging a New Frontier: Providing Palliative Care to People with Cancer in Rural and Remote Areas, a 2020 Journal of Clinical Oncology article, found that traditional geographically-based specialty care delivery models could be adapted to under-resourced rural practices and delivered using culturally appropriate methods. The 2020 article shared how primary care providers (PCPs) who received basic palliative care training resulted in reduced emergency room visits and hospital admissions among patients with serious illnesses but also reported on barriers to PCP-delivered palliative care, including:

- Lack of funding to cover palliative services

- Limited training opportunities

- Technology issues related to providing care to cover large geographic areas

- Lack of PCP expertise in palliative and home health technologies

- PCP perceptions that providing palliative care is burdensome to incorporate into their demanding schedules

In rural areas, physician shortages and turnover can make the referral process more difficult and create additional barriers related to care coordination. For more information on challenges faced by rural palliative care organizations, see What challenges are faced by rural palliative care organizations? on the Rural Hospice and Palliative Care topic guide.

The American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine article, Providing Hospice Care in Rural Areas: Challenges and Strategies, cited the following as obstacles hospice agencies in rural areas face when providing services:

- Low patient volume impacting finances

- Expensive medications

- Low or insufficient reimbursement, including Medicare

- Difficulty recruiting and retaining staff

What challenges are faced by rural hospice organizations? on the Rural Hospice and Palliative Care topic guide discusses challenges rural hospice organizations encounter when serving rural residents. In 2018, the Journal of Global Oncology released a guideline, Palliative Care in the Global Setting: ASCO Resource-Stratified Practice Guideline, to assist those seeking to implement palliative care in resource-constrained settings, including those in rural areas.

Challenges to accessing pediatric cancer care

Living in a rural setting while undergoing cancer treatment at an urban cancer center can present a number of challenges for pediatric patients and their families. A 2019 Journal of Oncology Practice article, Challenges Associated with Living Remotely from a Pediatric Cancer Center: A Qualitative Study, describes interviews conducted with caregivers of pediatric cancer patients who received cancer treatment at an urban cancer center. They expressed several concerns with care received from local hospitals, including:

- Lack of resources

- Trust in providers

- Poor communication between providers at their local hospital and the cancer center

- Lack of specialists' and subspecialists' understanding of the limitation of care available at their local hospital

The article discussed additional challenges reported by interviewees:

- A median estimated travel time of three hours per visit

- Added stressors during the long drive due to inclement weather or their child experiencing treatment-related symptoms not easily managed on the road

- Financial impacts and burdens from both the increased time away from work and travel-related expenses including food, gas, and lodging

For additional information on challenges related to healthcare access in rural areas and other barriers rural residents face related to access to care, see the Healthcare Access in Rural Communities topic guide.

What approaches have been successful in addressing distance-related barriers to care in rural areas?

Telehealth

Teleoncology is the use of audiovisual technology for patients to see cancer specialists and subspecialists in a virtual setting. For cancer patients living in rural areas, this technology can help bridge the gap in care that geographic barriers can create.

With Teleoncology, VA Stands Shoulder-to-Shoulder with Veterans in Rural Areas to Reduce Disparities in Cancer Care, a 2021 Vantage Point blog post from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), discusses the success the VA has experienced with providing teleoncology care for rural veterans. A 2017 BMJ Open article, Telehealth and Patient Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Narrative Analysis, found that telehealth helped lower missed appointments, decrease patient wait times, reduce readmissions, and improve medication adherence. Teleoncology is also being used more to deliver cancer support services such as mental health services, nutrition counseling, and palliative care.

There are a number of barriers to implementing and using telehealth services to provide care for rural cancer patients. For more information on barriers, regulations, and resources related to providing telehealth services in rural areas, see the Telehealth and Health Information Technology in Rural Healthcare.

Outreach clinics

In many rural states, agreements between rural clinics and larger health systems in urban areas allow specialists and subspecialists to travel to rural locations for a set number of days in a week or month to increase access and provide cancer care. While these outreach clinics can increase access to cancer care in rural healthcare facilities, the frequency of oncologist visits may not fit the medical needs for all patients. Specialists and subspecialists may only visit towns once or twice a month, so solely relying on outreach clinic visits for specialized care could cause delays in treatment. Trends in Medical Oncology Outreach Clinics in Rural Areas, a 2014 article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, discusses administrative challenges oncologists experienced while traveling to provide care in rural outreach clinics in Iowa, including job satisfaction, retention, productivity, non-reimbursable travel-related costs, and costs related to physician travel time and clinical outreach that is not eligible for reimbursement.

Virtual tumor board meetings

Telemedicine can be used to conduct virtual multidisciplinary tumor board meetings across healthcare facilities. A virtual multidisciplinary tumor board meeting can include physicians in cancer care from different specialties as well as people from other professions, such as patient navigators and social workers. This enables members from different healthcare systems, including those practicing in rural areas, to meet virtually to discuss and plan treatment options for a patient. Virtual tumor boards could be an especially useful resource for small, rural hospitals and clinics. However, healthcare providers practicing in rural and community settings have the challenge of balancing their time between providing clinical care and attending virtual tumor board meetings with enough frequency to meet the complex treatment needs of cancer patients. Virtual tumor board meetings do not provide compensation or reimbursement to healthcare providers for participation, which could be a deterrent for some providers leading them to seek faster forms of consultation, such as telephone calls or email. To limit the uncompensated time that goes into preparing to present a case to the virtual tumor board, some physicians may refer patients with complex needs to another provider.

Workforce initiatives

Workforce programs and incentives could be used to aid in recruitment and retention efforts to increase the oncology workforce in rural areas and improve access to cancer care. Examples of potential workforce initiatives include expanding loan repayment programs and other existing financial aid programs to include oncologists and other healthcare professions that are a part of the cancer care team and help provide cancer treatment.

To help with workforce issues, primary care physicians could play a larger role in some types of cancer follow-up care to allow oncologists to spend more time and attention on new diagnoses and treatment options. Another option is staffing cancer centers and clinics with advanced registered nurse practitioners or physician assistants to provide less complex cancer treatments through follow-up care and survivorship clinics, which could give oncologists more time to treat new or complex cancer patients.

Educational initiatives

Healthcare providers in rural areas can experience many challenges related to completing continuing education such as traveling long distances to teaching hospitals that provide in-person educational programs, time spent away from providing clinical care, and other issues caused by their absence. Telehealth can be used to provide real-time, interactive cancer education for rural healthcare providers who may not be able to travel or lack access to continuing education programs for other reasons. Cancer education programs could be particularly beneficial for healthcare providers who are not cancer specialists but provide cancer care for rural patients.

How do rural areas differ from urban in cancer survivorship?

Rural-Urban Disparities in Health Status Among US Cancer Survivors, a 2013 journal article in Cancer, analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2006 to 2010 examining rural and urban disparities in health status for cancer survivors. The article determined rural areas are home to an estimated 2.8 million cancer survivors who reported higher rates of fair or poor health status, one or more non-cancer comorbidities, mild-moderate and serious psychological distress, and unemployment due to health reasons relative to their urban counterparts. Rural-Urban Differences in Health Behaviors and Implications for Health Status Among US Cancer Survivors, a 2013 article in Cancer Causes & Control, also analyzed National Health Interview Survey data from 2006 to 2010 looking at differences in health behaviors for rural and urban cancer survivors. The authors determined the prevalence of physical inactivity was significantly higher in rural survivors (50.7%) compared to their urban counterparts (38.7%) and smoking among rural survivors (25.3%) was substantially higher than among urban survivors (15.8%). In addition, alcohol consumption was lower for rural survivors and no significant differences were found in obesity rates among rural and urban cancer survivors.

A 2022 article in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guideline for Cancer Survivors, recommends evidence-based guidelines related to nutrition and physical activity for cancer patients actively receiving treatment, cancer survivors immediately after treatment, and long term cancer survivors. The guidelines also include diet, nutrition, and physical activity recommendations for specific cancer types and includes considerations for rural populations.

An April 2019 Supportive Care in Cancer article, Rural-Urban Differences in Financial Burden among Cancer Survivors: An Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey, analyzed three years of data from NCI's Health Information and National Trends Survey and found that 50.5% of rural cancer survivors reported experiencing financial burdens from their diagnosis and treatment, compared to 38.8% of cancer survivors living in urban areas.

Long-Term Survivorship Care after Cancer Treatment: Proceedings of a Workshop, a 2018 publication from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, includes discussion and suggestions from cancer survivors, their caregivers, and healthcare providers on ways to improve survivorship care plans. It includes information and considerations on reaching rural cancer survivors and highlights a mobile survivorship clinic in rural Texas.

Are particular parts of the country more prone to cancer?

Appalachia

The Appalachian region in the U.S. spans across 423 counties in 13 states, including all of West Virginia and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. According to a June 2023 Appalachian Regional Commission publication, The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2017-2021 American Community Survey Chartbook, the region is home to approximately 26.3 million people and about 9.4% of that population lives in rural counties, which the report defines as counties that are not in or adjacent to a metropolitan area.

In Appalachia, cancer remains a leading cause of death. A 2016 Journal of Rural Health article, Cancer Disparities in Rural Appalachia: Incidence, Early Detection, and Survivorship, examined cancer mortality rates between 1969 and 2011 by rurality and Appalachian residence and found that starting around 1995 cancer incidence declined in every region of the U.S. except rural Appalachia. After 1995, rural Appalachia residents experienced higher cancer mortality rates compared to their urban and non-Appalachia peers.

Delta Region

The Delta Region is a federally designated region of 252 counties and parishes in 8 states along the Mississippi River and parts of Alabama. It has more than 10 million residents with a high proportion of rural, and many counties and parishes within this region are classified as economically distressed. A 2017 article in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, Cancer Mortality in the Mississippi Delta Region: Descriptive Epidemiology and Needed Future Research and Interventions, analyzed 2008-2012 mortality data and found that the Delta Region had higher cancer mortality rates for female breast, prostate, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancers than the rest of the country. Further, the rural areas in the Delta Region had higher cancer mortality rates compared to the urban areas of the Delta region and other rural regions throughout the country for all cancer types combined and for most of the individual cancer types mentioned earlier.

Cardiovascular & Cancer Rates for the Rural Delta Region, a mapping tool from the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, shares incidence data for 8 types of cancer for all counties and parishes in the Delta Region that can be compared by county or parish, rural status, to neighboring counties, and more.

How can policymakers support cancer prevention and control efforts in rural areas?

A 2019 National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services (NACRHHS) policy brief, Examining Rural Cancer Prevention and Control Efforts, provides recommendations on rural cancer prevention and control efforts that include:

- Greater collaboration across federal agencies to develop a rural patient navigation program to improve cancer care

- Increased funding for rural cancer research and partnerships to carry out rural and tribal cancer control projects

- National educational campaigns for rural healthcare providers to promote clinical information and resources on cancer

- Targeted outreach from CMS to rural providers on the use of cancer-relevant Medicare codes to bill for care coordination

- Requiring that state, territorial, and tribal organizations address rural cancer mortality within their cancer control plans and include rural specific goals and measures if appropriate

The American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) regularly releases a report, How Do You Measure Up? A Progress Report on State Legislative Activity to Reduce Cancer Incidence and Mortality, detailing how states are doing regarding important cancer policies such as Medicaid coverage for cancer screening and treatment, tobacco taxation policies, and other cancer relevant policies. ACS CAN also has a library of public policy resources that is searchable by keyword and issue, including rural.

What are federal agencies doing to address rural cancer control?

National Cancer Institute

In 2017, leadership at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) advocated for further investment into research on rural cancer disparities after a 2017 Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention article, Making the Case for Investment in Rural Cancer Control: An Analysis of Rural Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Funding Trends, found that only 3% of research grants funded through its primary grant mechanisms focused on rural health issues. In 2018, NCI hosted the Accelerating Rural Cancer Control Research Meeting in partnership with other federal agencies including the Health Resources and Services Administration's Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' (CMS) Rural Health Council and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More than 250 researchers, medical and public health practitioners, and representatives of community organizations participated in the meeting to identify gaps in the research, build partnerships to address challenges in rural cancer prevention and control, and develop recommendations to accelerate rural cancer control. The 2018 Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention article, An Overview of the National Cancer Institute's Initiatives to Accelerate Rural Cancer Control Research, provides a synopsis of the meeting and describes the recommendations to address rural cancer control. In addition to traditional grant mechanisms established to promote rural-focused cancer research, NCI incentivized NCI-Designated Cancer Centers by providing supplemental funding to 27 centers throughout 2018 and 2019 to develop cancer control research capacity in rural and tribal communities.

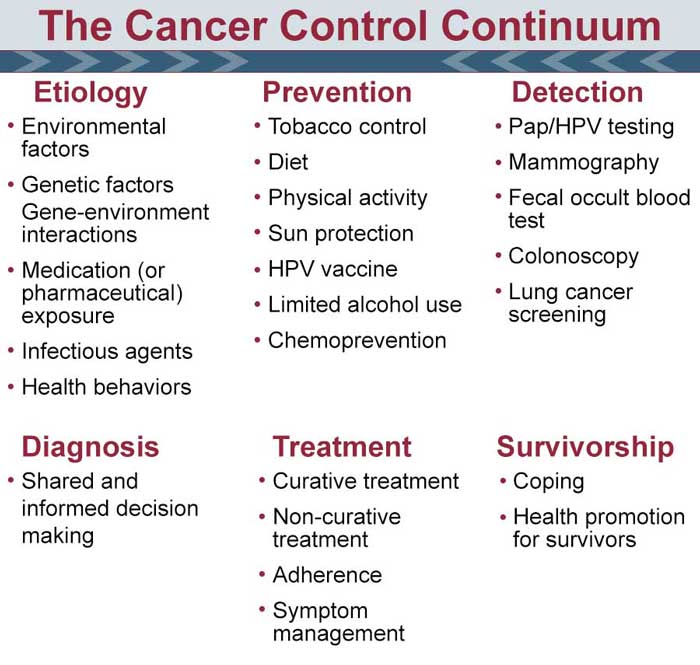

NCI follows the cancer control continuum framework to plan priorities. The cancer control continuum also describes the different phases of cancer, including etiology or cause, prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the MMWR Rural Health Series highlighting rural health disparities, including several articles addressing cancer incidence, staging, and mortality; cancer-related health behavior; and cancer health services. The staging of a cancer diagnosis refers to the size of the tumor and if it has spread to other tissues in the body. The 2018 CDC policy brief, Public Health Strategies for Rural Cancer Policy Brief, provides specific recommendations for preventing and treating cancer in rural areas, including:

- Working with faith-based organizations to provide evidence-based smoking cessation resources

- Low or no-cost HPV vaccinations

- Promoting stool-based tests for colorectal cancer screenings

- Expanding options for patient transportation

The Division of Cancer Prevention and Control within the CDC supports two programs that provide no-cost cancer screenings to patients who have low-income, are uninsured, or are underinsured:

- National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP)

- Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP)

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines free of charge, including HPV vaccines, to eligible children and adolescents aged 18 and younger. CDC purchases vaccines at a discount and provides them to state health departments, local and territorial public health agencies, and other grantees for further distribution to registered VFC providers such as private physicians' offices, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), and public health agencies.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP) assists states, territories, and tribal organizations with developing comprehensive cancer control plans that serve as blueprints of cancer control priorities within their respective state, territory, or organization. An interactive directory of comprehensive cancer control plans (CCCPs) and program contact information is available online. The 2021 Preventing Chronic Disease article, Extent of Inclusion of "Rural" in Comprehensive Cancer Control Plans in the United States, shares the results of a study examining 66 CCCPs to assess the inclusion of rural-specific information and data in the plan goals, objectives, and strategies to address cancer disparities.

Health Resources and Services Administration

HRSA's Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) supports FQHCs that serve 1 in 5 rural residents and can provide a variety of healthcare services that can include preventive cancer screening and care. For example, the National Association of Community Health Centers and the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable champion colorectal cancer screening among these centers, which showed a nearly 50% increase in the percentage of patients up-to-date with screening between 2012 and 2018.

HRSA and NCI have collaborated to provide funding for research focused on rural cancer through HRSA-funded Rural Health Research Centers. Throughout the more than 20-year history of this program, numerous projects, policy briefs, peer-reviewed journal articles, and other research products have focused on cancer in rural populations and are available on the Rural Health Research Gateway.

The Rural Monitor article Federal Agencies' Investment in Rural Cancer Control Fosters Partnerships between Researchers and Rural Communities discusses how federal agencies are supporting projects focused on rural cancer prevention and control.