Substance Use and Misuse in Rural Areas

Though often perceived to be a problem of the inner city, substance use and misuse have long been prevalent in rural areas. Rural adults have higher rates of use for tobacco and methamphetamines, while opioid use has grown in towns of every size. Rural adolescents and young adults use alcohol at higher rates and are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors, like binge drinking or driving under the influence, than their urban counterparts.

Substance use can be especially hard to combat in rural communities due to limited resources for prevention, treatment, and recovery. According to The 2014 Update of the Rural-Urban Chartbook, the substance use treatment admission rate for nonmetropolitan counties was highest for alcohol as the primary substance, followed by marijuana, stimulants, opiates, and cocaine.

Factors contributing to substance use in rural America include:

- Low educational attainment

- Poverty

- Unemployment

- Lack of access to mental healthcare

- Isolation and hopelessness

- A greater sense of stigma

Substance use disorders can result in increased illegal activities as well as physical and social health consequences, such as poor academic performance, poorer health status, changes in brain structure, and increased risk of death from overdose and suicide.

This topic guide covers the effect of substance use on rural communities, broadly. For information and resources specific to the opioid crisis, see the Rural Response to the Opioid Crisis topic guide.

| Substance Use | Non-metro | Small metro | Large metro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use by youths aged 12-20 | 30.9% | 28.4% | 25.3% |

| Binge alcohol use by youths aged 12 to 20 (in the past month) | 11.2% | 8.5% | 6.3% |

| Cigarette smoking | 22.5% | 17.3% | 14.5% |

| Smokeless tobacco use | 6.0% | 3.6% | 2.4% |

| Marijuana | 21.0% | 22.4% | 22.5% |

| Illicit drug use | 24.3% | 25.5% | 25.8% |

| Misuse of opioids | 3.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% |

| Cocaine | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Hallucinogens | 2.6% | 3.1% | 4.1% |

| Methamphetamine | 1.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Inhalants | 0.8% | 0.9% | 1.3% |

| Source: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. | |||

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the difference between substance use disorder, substance use, and misuse?

- What effects does substance use have on a rural community? What challenges do rural communities face in addressing substance use and its consequences?

- How can rural communities combat substance use?

- What are the options for addressing tobacco use in rural communities?

- How prevalent is underage drinking and binge drinking in rural communities?

- How big a concern is alcohol-impaired driving in rural communities, and what are some options to reduce it?

- What can be done to discourage youth from using drugs and alcohol?

- What is opioid misuse, and what effect has it had in rural communities?

- What is the current status of methamphetamine use in rural America, and what has been done to combat its use and production?

- How can rural primary care providers help address substance use and connect their patients to substance use disorder treatment?

- How can rural areas develop local options for those who need treatment?

- How can rural communities support post-treatment recovery?

What is the difference between substance use disorder, substance use, and misuse?

Substance use, in the broadest terms, is any ingestion of mood- or behavior-altering substances, such as alcohol, nicotine, and illegal drugs. Substance misuse is the use of any substance that is outside the prescribed or intended use of that substance, such as off-label usage of prescription drugs or underage drinking.

Prolonged use of these substances can result in substance use disorder (SUD), which can affect not only the individual, but the person's family and community.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), substance use disorders (SUDs):

“occur when the recurrent use of alcohol and/or drugs causes clinically significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home.”

The behavioral signs of substance use disorder may include:

- Lack of motivation

- Repeated absences or poor work performance

- Neglect of children or household

- Car accidents

- Interference with sleeping or eating

- Need for privacy

- Outbreaks of temper

- General changes in overall attitude

- Deterioration of physical appearance and grooming

- Need for money and stealing money or valuables

- Persistent dishonesty

- Secretive or suspicious behavior

What effects does substance use have on a rural community? What challenges do rural communities face in addressing substance use and its consequences?

Substance use and misuse within a rural community can present many problems. Increased crime and violence, vehicular accidents caused by driving while intoxicated, spreading of infectious diseases, fetal alcohol syndrome, risky sexual behavior, homelessness, and unemployment may all be the result of one or more forms of substance use.

These problems are exacerbated by several unique challenges for rural communities:

- Behavioral health and detoxification (detox) services are not as readily available in rural communities and, for those that are available, their range of services may be limited.

- Patients who require treatment for substance use disorder may need to travel long distances to access services.

- Rural first responders or rural hospital emergency room (ER) staff may have limited experience in providing care to a patient presenting with the physical effects of a drug overdose.

- Law enforcement and prevention programs may be sparsely distributed over large rural geographic areas.

- Patients seeking substance use disorder treatment may be more hesitant to do so because of privacy issues associated with smaller communities. Rural communities often lack housing and support services for long-term recovery.

How can rural communities combat substance use?

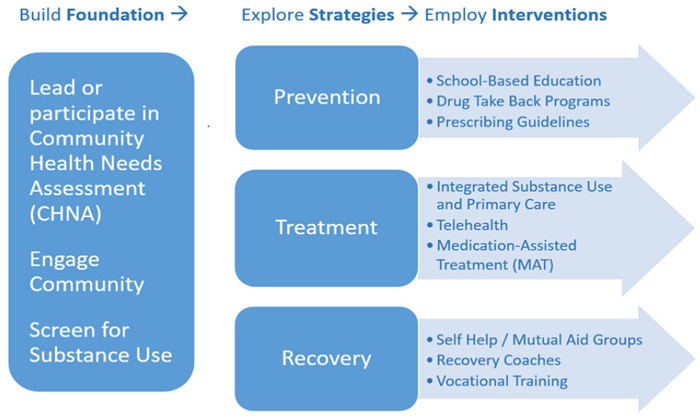

Prevention programs can help reduce substance use in rural communities, particularly when focused on adolescents. Programs using evidence-based strategies that involve parents within schools and churches may discourage substance use by younger adults.

Counselors, healthcare professionals, teachers, parents, and law enforcement can work together to identify problems and develop prevention strategies to control substance use in rural communities by:

- Holding community or town hall meetings to raise awareness of the issues

- Training law enforcement regarding liquor license compliance, underage drinking, and detection of impaired drivers

- Inviting speakers to talk to school-aged children and help them understand the consequences of substance use

- Conducting routine screening in primary care visits to identify at-risk children and adults

- Collaborating with churches, service clubs, and employers to provide a strong support system for individuals in recovery, which might include support groups and tobacco quitlines

- Training volunteers to identify and refer individuals at risk

- Developing formal substance use prevention, treatment, or recovery programs for the community

- Providing care coordination and patient navigation services for people with substance use disorders

- Providing specialized programs and counseling to discourage substance use by pregnant women

- Collaborating with human services providers and local service organizations to ensure families affected by substance use disorder have adequate food, housing, and mental health services

- Providing emergency departments (EDs), first responders, and the public with training and access to overdose reversal drugs.

Existing healthcare facilities in a community can play an important role in combating and addressing substance use and substance use disorder. In Engaging Critical Access Hospitals in Addressing Rural Substance Use, the Flex Monitoring Team outlines a framework for Critical Access Hospitals to address their communities' needs, from prevention to treatment to recovery.

For additional activities and evidence-based interventions to combat substance use, see the Evidence-Based and Promising Substance Use Disorder Program Models section of the Rural Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Toolkit.

What are the options for addressing tobacco use in rural communities?

According to the Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, tobacco product use for young adults aged 18-25 was 30.6% in nonmetro areas, compared to 22.6% in large metro areas. Given the link between tobacco use and diseases such as cancers, chronic pulmonary obstructive disorder (COPD), heart disease, and stroke, this high rate of tobacco use is an important contributor to rural health disparities.

FDA 101: Smoking Cessation Products identifies a number of tobacco cessation products that can help tobacco users break their addiction, including nicotine replacement products, such as skin patches, gum, lozenges, and prescription drugs.

There are several federal programs, such as Smokefree.gov, that offer resources and quitlines for tobacco users looking for support. There are also a number of youth-led initiatives and programs focused on tobacco prevention among young people, such as the Truth Initiative, that work to prevent young people from starting to use tobacco. Programs working to change tobacco policies on the local and state level are another resource.

The use of e-cigarettes, or "vaping", is the newest and most pervasive form of nicotine use among teens and young adults. Though the effects of vaping are still being studied, there are already a number of programs dedicated to vaping prevention in rural communities, as highlighted in the 2020 Rural Monitor article Drug Education and Cessation Programs Help Teens Avoid or Quit Vaping.

For additional program examples, see Tobacco use in Rural Health Models & Innovations.

How prevalent is underage drinking and binge drinking in rural communities?

According to SAMHSA's Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, alcohol use in the past month among 12-20 year olds was 16.0% in nonmetro areas, compared to 11.7% in large metro areas. Binge alcohol use (5+ drinks for males, 4+ drinks for females on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days) in the past month for the same age group was 11.2% in nonmetro areas compared to 6.3% in large metro areas and heavy alcohol use (binge drinking 5+ times in 30 days) was 3.2% in nonmetro areas and 1.0% in large metro areas. A 2013 JAMA Pediatrics article concluded that rural high school students are more likely to participate in extreme binge drinking (15+ drinks).

Adolescent Alcohol Use: Do Risk and Protective Factors Explain Rural-Urban Differences?, a study from the Maine Rural Health Research Center, suggests that adolescents who begin drinking alcohol at an early age may engage in problem drinking as they get older. Additionally, rural adolescents reported higher rates of driving under the influence (DUI) than urban adolescents.

Several characteristics may affect the attitude of adolescents and influence the prevalence of underage drinking and binge drinking:

- Lower levels of parental disapproval of underage drinking

- Higher acceptance of peer alcohol use among rural adolescents

- Easier access to alcohol at family events and from adults purchasing alcohol for underage youth

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) publication, Preventing Drug Abuse among Children and Adolescents, research demonstrates that high levels of risk are usually accompanied by low levels of protective factors or prevention.

How big a concern is alcohol-impaired driving in rural communities, and what are some options to reduce it?

According to the report Traffic Safety Facts, 2023 Data: Rural/Urban Traffic Fatalities, there were 12,429 people in the U.S. killed in crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers in 2023. Rural areas accounted for 40% (4,987) of these fatalities and 30% of all rural traffic fatalities were alcohol-related.

While various states are imposing stricter drunk driving laws in an attempt to control this problem, some local communities are using other approaches to reduce drunk driving. For example, communities may implement transportation options for those who may be too impaired to drive, such as the Isanti County Safe Cab Program in Minnesota. This program has considerably reduced the number of DUI arrests in the county. In addition, this same rural county developed the Staggered Sentencing for Repeat Drunk Driving Offenders program, which allows offenders to serve their sentence in segments of time and potentially have future segments waived pending full compliance with the program's guidelines. The goal of this program was to reduce the occurrence of repeat DUI violations and improve public safety by providing some assistance to help offenders resist driving under the influence of alcohol.

What can be done to discourage youth from using drugs and alcohol?

Everyone can help educate children and youth on the dangers of illegal drugs and alcohol. A 2012 study published by the Maine Rural Health Research Center suggested that, first and foremost, parental influence is a protective factor against alcohol use. There are programs to help schools, churches, organizations, and parents who want to work with youth to discourage them from using alcohol and other drugs.

Family-centered prevention programs work to improve the knowledge and skills of children and parents related to substance use, as well as the communication within the family.

Schools can play a part in discouraging youth from using drugs and alcohol. Schools provide a stable and supportive environment for students where they feel cared for by teachers and staff. Children who are successful in school are less likely to drink alcohol.

Rural church and faith-based organizations can also play an important role in promoting substance use prevention. According to the 2012 study listed above, rural adolescents are more inclined to participate in organized church-related events and could benefit from activities focused on substance use prevention.

Several evidence-based prevention programs designed to reduce substance use by children and youth that can be implemented in schools, churches, and other settings are listed in the Appendix of the 2012 study.

Other organizations that provide substance use information and prevention program resources for youth include:

-

National Institute on Drug

Abuse

(NIDA)

Lists websites and materials that teachers and parents can use for prevention activities and education of children and teens. -

Helping Kids PROSPER

PROSPER (PROmoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience) offers evidence-based systems for program development in rural schools and communities. Community leaders and educators can utilize PROSPER to develop programs that reduce risky behaviors, such as underage drinking and illicit drug use. -

keepin' it REAL Rural

The rural-specific version of the keepin' it REAL drug and alcohol prevention program for middle school students, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Several other prevention programs can be found in the Rural Substance Use Disorders Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Toolkit's section on Prevention Models.

What is opioid misuse, and what effect has it had in rural communities?

Opioid misuse refers to any use of heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, or prescription pain relievers, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, and morphine outside their prescribed or intended use. According to the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 7.2 million adults misused prescription opioids at least once in the previous year, with approximately 1.2 million of those adults in a nonmetropolitan area.

According to the 2024 report, 3.7% of adults in nonmetro areas and 2.6% of adults in large metro areas reported non-medical use of prescription opioids in 2024. A 2015 study from the Carsey School of Public Policy showed that rural adolescents were more likely to misuse prescription painkillers than urban adolescents.

Prescription drug misuse in the early 2000s led to the increased use of heroin, followed by synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl. A 2013 study from SAMHSA's Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality found that people who used opioids non-medically were 19 times more likely to initiate heroin use. According to a 2014 JAMA Psychiatry article, heroin became more prevalent in suburban and rural areas because of its affordability and ease of access compared to prescription opioids. Heroin, a drug that is predominantly injected, presents its own health risks, such as an increased likelihood of hepatitis C (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, as well as the risk of unintentional overdose.

According to a 2021 report from the USDA Economic Research Service, the rates of overdose deaths from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, tramadol, and meperidine, surpassed both the rates for heroin and prescription opioids around 2015 and continues to rise over the latter half of the decade.

Mortality

According to a 2022 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the rate of drug overdose fatalities was slightly higher in urban areas (28.6 per 100,000) than in rural areas (26.2 per 100,000) in 2020. For opioids specifically, urban counties had 31% higher mortality for heroin and 28% higher mortality for synthetic opioids, but rural counties had a 13% higher mortality rate for natural and semisynthetic opioids. The CDC's Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes for 2019 shows that opioids were responsible for approximately 63% of drug overdose deaths in rural (micropolitan and noncore) areas of the country in 2017.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

A May 2015 MMWR article reported an increase in the number of persons in the U.S. living with HCV, particularly with young adults under 30 years old. Increases were most noticeable in nonurban areas of Appalachia where injection drug use (IDU) has been identified as the primary risk factor for HCV. Approximately 73% of the reported HCV cases in this area were contracted by people reporting IDU.

Although not as prevalent in injection drug users as HCV, HIV infections can potentially increase concurrently with HCV because the risk factors are similar. According to a 2014 study, the 2011 rate of HIV infections among people who inject drugs was 55 per 100,000 people, compared to the HCV infection rate of 43,126 per 100,000 people in the same cohort. HIV and HCV are blood-borne diseases that are effectively transmitted through the use of contaminated needles and equipment used for preparing drugs, according to a November 2012 MMWR article.

Social Harm

There are a number of societal risks from the proliferation of illicit drug use. Increased drug-related crime may occur in a community, including crimes that result from a substance-altered mental state, crimes committed to fund drug use, and crimes related to the production and distribution of illegal drugs.

Drug use also has physical and social consequences for the children of drug users. According to a National Institute on Drug Abuse research report, there is evidence that prescription pain reliever use during pregnancy can lead to a 2.2 times greater risk of stillbirth. Heroin use during pregnancy can lead to neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), wherein the baby is born dependent on opioids.

For more information and resources specific to the opioid crisis, see the Rural Response to the Opioid Crisis topic guide.

What is the current status of methamphetamine use in rural America, and what has been done to combat its use and production?

According to SAMHSA's Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, the rate of methamphetamine use by young adults ages 18–25 was 0.3% for large metro areas, 0.5% for small metro areas, 1.0% for nonmetro areas. This pattern of higher use in rural areas continues to be a great concern.

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) report, 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary, police reports for methamphetamine has risen 75% since 2014 and had gone from 9% of all drug reports in 2009 to 24% in 2018. Although seizures of covert meth labs in the U.S have decreased, availability is still high due to foreign production and the proliferation of small, "one pot," or "shake-and-bake" laboratories, which are harder to track down. Admissions for amphetamine-related treatment continue to increase.

The Meth Project Foundation, Inc. is a national program of The Partnership for Drug-Free Kids that focuses on reducing methamphetamine use through public service media, outreach programs, and the development of public policy. It also is a source of information for youth about meth.

Is treatment for substance use disorders available in rural areas?

States with proportionally large rural populations (compared to urban populations) have greater shortages of mental health providers and fewer facilities to provide treatment services. Although family doctors, psychologists, social workers, and pastors may be available in rural areas to deliver basic substance use services or social support, facilities available in rural areas that provide comprehensive substance use treatment services are limited. A 2019 study found that on top of the usual barriers to healthcare access for rural people, such as travel time and cost of care, there was a lack of treatment programs available in rural areas and a negative perception of treatment for substance use disorder among rural providers.

According to the 2014 Substance Use & Misuse article, Barriers to Substance Abuse Treatment in Rural and Urban Communities: Counselor Perspectives, rural areas lack not just basic treatment services but also supplemental services necessary for positive outcomes. Detoxification (detox) services, for example, provide the initial treatment for patients to minimize any medical or physical harm caused by substance use. The vast majority (82%) of rural residents live in counties that do not have detox services, reports Few and Far Away: Detoxification Services in Rural Areas. Often, local law enforcement or emergency departments provide the initial detox services.

In addition, depending on the stage of their illness, patients may need more advanced treatment services, such as inpatient, intensive outpatient, and/or residential care, not available in many rural areas. The absence of these treatment services locally results in clients having to travel long distances to receive the proper care. According to the 2014 Substance Use & Misuse article mentioned earlier, this greater distance to substance use disorder treatment often results in lower completion rates of substance use treatment programs. Rural communities often lack public transportation services, which can further impede access to ongoing treatment and support groups, particularly for clients who have had their driver's licenses revoked.

How can rural primary care providers help address substance use and connect their patients to substance use disorder treatment?

Rural primary care providers can play a key role in addressing substance use by screening to identify patients suffering from substance use disorder (SUD), encouraging those patients to seek treatment, and making referrals to appropriate treatment services. The screening process is a crucial first step towards treatment for SUD but in rural areas there are still barriers, such as a lack of training for providers, concerns about privacy and stigma, and a hesitancy to disclose substance use when a strong patient-provider relationship is not present, according to a 2019 study.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) is a professional society dedicated to improving the quality of addiction treatment by educating physicians and other medical professionals, as well as the public. ASAM provides a variety of courses and events, including continuing medical education (CME) courses. ASAM Education Resources lists both live and distance CME courses.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality offers a guide, Implementing Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) in Rural Primary Care, which discusses some of the barriers to establishing MAT in a rural primary care setting and includes 250 tools and resources that help facilitate implementation. For an in-depth look at medication treatment in rural America, see the 2018 Rural Monitor article, What's MAT Got to Do with It? Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Rural America.

SAMHSA supports an online facility locator that rural primary care providers can use to find treatment centers and services in their region:

-

Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

Locate treatment facilities addressing substance use, addiction, and mental health problems by zip code or city and state.

How can rural areas develop local options for those who need treatment?

Recently there has been a trend to co-locate or integrate mental/behavioral health services with primary care services. This approach could facilitate access to substance use disorder treatment and reduce the stigma associated with behavioral health treatment. Providers are then able to network and work together rather than work in an isolated environment. The Rural Mental Health Topic Guide provides additional information on this topic.

There are a number of available treatment models for expanding treatment for substance use disorder in rural areas:

Project ECHO® – Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes connects rural primary care providers with academic specialists to address patients' chronic care, including substance use.

The Vermont Hub-and-Spoke Model of Care for Opioid Use Disorder expands access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder to rural areas through urban hubs throughout the state.

The Indiana's Integrated Care Training Program: Community Health Worker/Certified Recovery Specialist program addresses behavioral health issues in rural areas by training community health workers (CHWs) to provide support services in a variety of settings, including emergency and outpatient settings.

For additional program examples, see Substance use and misuse in Rural Health Models & Innovations.

For a step-by-step guide to implementing a rural substance use treatment program, see the Rural Substance Use Disorders Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Toolkit.

How can rural communities support post-treatment recovery?

Recovery is a broad and important step in overcoming and managing substance use disorder (SUD). Because substance use and misuse can affect every aspect of a person's life, recovery often requires support in a variety of areas beyond clinical care, particularly in the early stages of recovery. Supports such as housing, job training and employment, mutual aid, mental healthcare, and peer support can be instrumental in setting people up for success following SUD treatment. Recovery programs can be sparse in rural areas, though programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) are often available.

There are a number of SUD recovery models featured in the Rural Substance Use Disorders Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Toolkit that are proven to work in rural communities. These models can be used to create a recovery program that fits the specific needs of the community.

Examples of successful rural recovery projects include:

- Recovery Kentucky – Provides apartments within a congregate living environment and an opportunity to begin recovery from SUD via a peer-led 12-step environment in 8 locations in rural Kentucky.

- Addiction Recovery Mobile Outreach Team (ARMOT) – Provides case management and recovery support services to individuals with SUD and education and support to rural hospital staff, patients, and their loved ones.

- Seneca Strong's Certified Addiction Recovery Coaches – Provides a cultural recovery peer advocate program, with the goal of reducing substance misuse across the Seneca Nation.

- Community Action Commission of Fayette County Faith in Recovery Coalition – Provides a detox facility, inpatient treatment, and recovery housing via a collaboration between the government, a nonprofit, and faith-based organizations.

Often recovery involves addressing the underlying psychological processes associated with substance use. For more information on mental healthcare in rural communities, see our Rural Mental Health topic guide.