Rural Maternal Health

Maternal healthcare is a critical issue in the United States. According to The Commonwealth Fund’s article, The U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis Continues to Worsen: An International Comparison, maternal mortality in the U.S. is three times higher than most other high-income countries, and that gap continues to widen over time.

Access to consistent maternity care, reproductive services, postpartum support, and paid leave are some of the issues rural women face. Rural counties that are socioeconomically disadvantaged and experience other health disparities see higher rates of maternal morbidity and mortality.

As rural maternal health access has diminished, rural communities have been working to find innovative ways to protect the lives and health of rural mothers and babies. Supportive policies and access to maternal health programs and services help in addressing these health disparities. This topic guide covers rural maternal health disparities, issues of access, barriers to rural maternal well-being, workforce challenges, and ways rural communities are addressing these problems.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What disparities exist related to rural maternal and infant health?

- What issues of maternal healthcare access and utilization exist in rural America?

- What are the workforce challenges in providing rural maternal health services?

- What other barriers and issues affect rural maternal health?

- What policies, programs, or models address challenges with affordability, accessibility, and quality of maternal health services in rural areas?

- What other resources are available to address maternal health?

What disparities exist related to rural maternal and infant health?

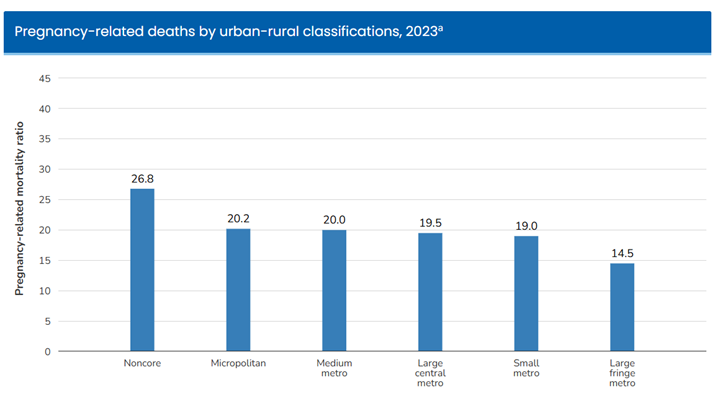

Rural women and infants experience significant health disparities when compared to their urban counterparts. According to the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, risks of pregnancy-related mortality are highest for rural populations, with 26.8 pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 occurring in noncore areas in 2023 and 20.2 deaths per 100,000 in micropolitan areas.

According to Rural-Urban Differences In Severe Maternal Morbidity And Mortality In The US, 2007–15, rural women have had a consistently higher predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity, such as sepsis, pulmonary edema, and acute renal failure, as well as mortality, even after accounting for sociodemographic factors and clinical conditions. According to the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health, rural mothers also experience higher rates of postpartum depression compared to urban mothers. These rural versus urban health disparities have continued to widen over time.

Rural/Urban Differences in Health, Health Care Use, and Barriers to Care for Postpartum and Parenting Women, 2006-2018 states that postpartum rural women are more likely to be hospitalized or need emergency room care compared to urban women. The 2023 article Rural–Urban Disparities in Adverse Maternal Outcomes in the United States, 2016–2019 states that maternal admission to intensive care units (ICU) was higher in rural areas, and rural women were at nearly twice the risk for mortality when compared to their urban counterparts.

Preconception health, or health status before a person becomes pregnant, also plays an important role in maternal health outcomes. According to Impact of Geography and Rurality on Preconception Health Status in the United States, rural areas were likelier than urban areas to show higher abbreviated preconception health risk index (aPHRI) scores, with risk factors such as poor nutrition, lack of influenza vaccine, and unhealthy weight being more common. The 2024 article, Disparities in Maternal Health Visits Between Rural and Urban Communities in the United States, 2016-2018, finds that rural mothers were less likely to have a doctor's visit in their prepregnancy year or during postpartum, and they were less likely to receive comprehensive screening and counseling during these time periods.

Disparities in health knowledge and behaviors impact maternal health. Obtaining fresh, nutritious food during pregnancy is critical, but according to the 2025 article Rural-Urban Differences in Dietary Intake Across Pregnancy Trimesters: A Multisite Prospective Cohort Study, women in rural areas had lower fiber intake and higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) than women in urban areas. Substance use during pregnancy is another health behavior that can affect outcomes for rural women. According to the 2025 article Rural-Urban Disparities in Perinatal Smoking in the United States: Trends and Determinants, smoking was more prevalent among pregnant rural mothers, who were 45% more likely to smoke than urban mothers.

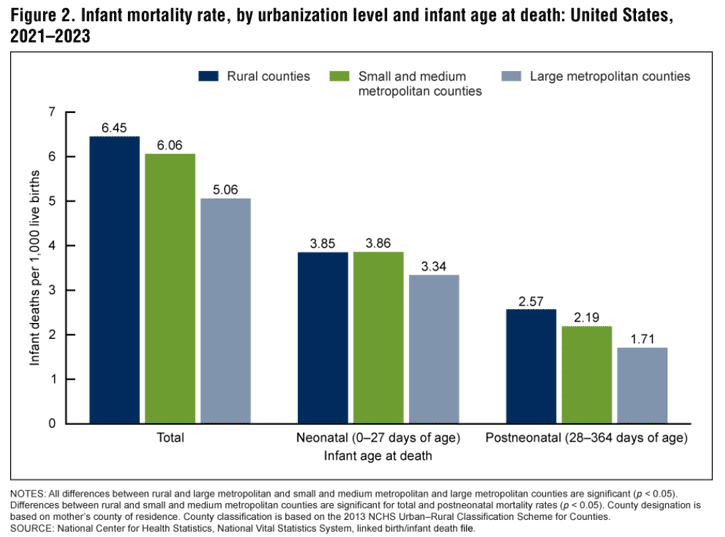

Consistent with their mothers, rural infants experience health disparities as well. According to Infant Mortality in Rural and Nonrural Counties in the United States, there are greater odds of infant mortality in noncore and micropolitan counties compared to large metropolitan fringe counties. The study explains that the odds ratio of mortality increases according to rurality and is associated with increased socioeconomic disadvantage experienced in many rural counties.

Trends and Differences in Infant Mortality Rates in Rural and Metropolitan Counties in the United States, 2021-2023 finds that infant mortality rates, including post-neonatal, were highest in rural counties from 2021 to 2023. The study also finds that mortality rates were higher in rural counties among infants born to mothers older than 30 years of age.

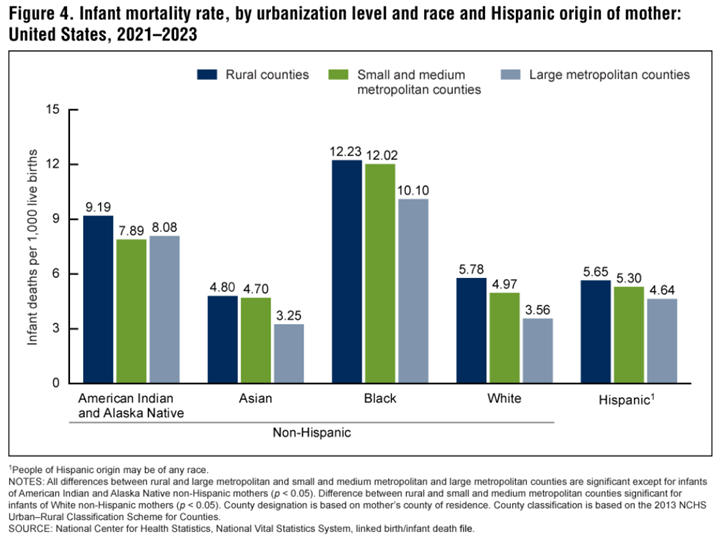

Across all racial/ethnic groups, infant mortality rates were higher in rural counties.

This same 2025 CDC report found that from 2014 to 2023, rates of rural infant mortality stayed relatively unchanged, remaining higher than among metropolitan counties.

Premature birth is another health disparity that disproportionately impacts rural families. Trends in Singleton Preterm Birth by Rural Status in the U.S., 2012-2018 finds that a higher percentage of singleton births were preterm in rural areas compared to urban (8.3% vs. 7.9%), and the highest rate of preterm births was in the rural South (9.6%). For more information on rural maternal health disparities and ways the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is working to address them, see the Exploring Rural Health podcast episode, National Rural Health Day Episode: Addressing Rural Maternal Health Disparities, with Kristen Dillon.

What issues of maternal healthcare access and utilization exist in rural America?

Access to maternal healthcare is essential to improve outcomes for mothers and their babies. Unfortunately, many rural women face barriers in accessing maternity care, such as transportation issues, physical distance, financial burden, insurance status, and availability of obstetric services. According to Obstetric Care Access Declined in Rural and Urban Hospitals Across US States, 2010-22, rural areas are experiencing a significant burden of obstetric service closures in short-term acute care hospitals, with 25% losing obstetric care services between 2010 and 2022. A 2025 study finds that 52.4% of rural hospitals did not offer obstetric services in 2022 compared to 35.7% of urban hospitals.

Closures can have a significant impact on maternal health outcomes in rural areas, because maternal health access and utilization are crucial to the ongoing wellness of mothers and their babies. Lack of access to maternal healthcare can contribute to several negative outcomes:

- Premature birth

- Low birthweight

- Maternal mortality

- Severe maternal morbidity

- Postpartum depression

According to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) report, Improving Access to Maternal Health Care in Rural Communities, maternal and infant health services are needed at the following times:

- Before pregnancy

- During pregnancy

- Prenatal

- Labor and delivery

- Immediately postpartum

- After pregnancy

Access to insurance coverage, obstetric services, and mental healthcare can improve health outcomes for rural women and their babies.

Insurance Coverage: Access to insurance during all stages of the maternity cycle, from prepregnancy through postpartum, is an important factor in maintaining health. According to Rural and Urban Differences in Insurance Coverage at Prepregnancy, Birth, and Postpartum, rural mothers had higher rates of uninsurance during all three maternal periods compared with their urban counterparts. During the years 2016-2019, rural residents had a 15.4% rate of uninsurance during prepregnancy versus 12.1% of urban residents, 4.6% at birth compared to 2.8% of urban residents, and 12.7% during the postpartum period compared to 9.8% of urban residents.

Many women access health insurance through Medicaid, which is the single largest payer for perinatal care, covering 41% of births nationally, including 47% of rural births. According to an analysis from Georgetown University, a higher proportion of women of childbearing age (15-44) with Medicaid coverage live in rural areas compared to urban (23.3% compared to 20.5%, respectively). For those on Medicaid, continued coverage is required for at least 60 days postpartum. Pandemic-related legislation provided states the opportunity to expand postpartum coverage to 12 months, and more recent federal legislation has made this option permanent. According to KFF, as of January 17th, 2025, 49 states, including Washington, DC, have extended Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum, with 3 states planning to expand coverage and 1 state proposing limited expansion.

Access to Obstetric Services: Closures of rural hospitals, labor and delivery units, and obstetric services also contribute to lack of access for rural residents. Addressing the Impact of Rural Hospital Closures on Maternal and Infant Health states that 50% of rural counties do not have access to hospital obstetric services. See 2010-2023 County-Level Hospital-Based Obstetric Care Status for a county-level study that indicates if a county had access to hospital-based obstetrics between 2010-2023. See Availability of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in the United States by County, 2010-2023: A State-by-State Report for more information.

Access to appropriate infant care can also be an issue in rural areas. According to the 2025 article Local Availability of Neonatal Intensive Care at Rural Hospitals with Childbirth Services, most surveyed rural hospitals did not have a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) available.

Poor socioeconomic conditions, cost of healthcare, and access barriers such as transportation and lack of paid leave all contribute to negative maternal and infant health outcomes. According to Closure of Labor & Delivery Units in Rural Counties is Associated with Reduced Adequacy of Prenatal Care, Even When Prenatal Care Remains Available, a resulting impact of labor and delivery unit closures is lowered utilization of prenatal care, especially for Medicaid recipients. Healthcare system disruptions such as closures have the potential to most severely impact those with already strained resources.

Improving Financial Access to Maternal and Infant Care in Rural Areas discusses strategies to improve maternal and infant healthcare access, such as improving Medicaid initiatives, utilizing value-based care systems, and leveraging the perinatal workforce. Innovations in Rural Obstetrics to Maintain Access to Care features 6 sustainable examples of communities improving access for their populations, focusing on partnerships, community-centered care, quality initiatives, culturally competent care, rural workforce development, and community engagement.

Mental Healthcare for Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Access to mental healthcare for pregnant and postpartum women in rural communities can be difficult to find. 'A Silent, Unmet Need': Rural Motherhood and the Challenges of Postpartum Care discusses programs that support rural mothers via postpartum doulas, telehealth, and home visiting. Rural maternal healthcare providers who do not have on-site access to mental healthcare for their patients may refer them to the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline at 1-833-TLC-MAMA (1-833-852-6262), which provides immediate support to pregnant women, mothers, and new parents at no cost. For more information on mental health disparities in rural populations, see our Rural Mental Health topic guide.

What are the workforce challenges in providing rural maternal health services?

Maternal healthcare services and support can be provided by several types of practitioners, including:

- Obstetricians/gynecologists

- Advanced practice nurse midwives

- Midwives

- Family physicians

- Doulas

Rural areas face challenges in sustaining a maternal healthcare workforce. A HRSA brief, State of the U.S. Maternal Health Workforce, 2025, finds that maternal health physicians disproportionately practice in large metropolitan areas relative to the female population of childbearing age, with the exception of family medicine physicians:

| Rurality | Family Medicine Physicians | General Internal Medicine Physicians | OBGYN Physicians | Neonatal and Perinatal Physicians | Female Population, Ages 15-49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large metropolitan area | 27.2% | 38.5% | 37.0% | 40.9% | 30.9% |

| Medium metropolitan area | 37.5% | 42.1% | 41.6% | 45.4% | 36.5% |

| Small metropolitan area | 24.4% | 15.9% | 17.3% | 12.3% | 22.4% |

| Micropolitan area | 9.6% | 3.4% | 4.0% | 1.3% | 9.2% |

| Noncore area | 1.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.05% | 1.0% |

| Source: State of the U.S. Maternal Health Workforce, 2025, Table 4 | |||||

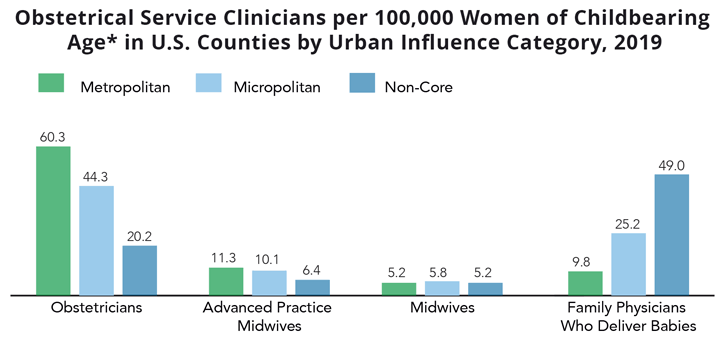

According to The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S., fewer obstetricians and advanced practice midwives per woman of childbearing age practice in micropolitan and non-core areas, but there is a comparable midwife density and a higher density of family physicians who deliver babies in those areas:

The reliance on family physicians for maternal health may be a concern when considering the turnover of rural family medicine physicians. According to Mobility of US Rural Primary Care Physicians During 2000–2014, younger physicians, women, and those born in urban areas are more likely to leave rural practices, which may compound the maternal health workforce shortage in these areas.

According to Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S., 59% of rural counties are maternity care deserts. However, due to the unpredictable nature of childbirth, some deliveries will happen in rural facilities even when obstetric services are not offered. Obstetric Readiness in Rural Communities Lacking Hospital Labor and Delivery Units promotes obstetric readiness for emergency units in rural hospitals without obstetric units. The article emphasizes the importance of supporting community-based, emergency department-adjacent health workers in areas that lack comprehensive obstetric services.

Utilizing many types of maternal health practitioners in rural areas may help to mitigate shortages. However, Access to Maternity Providers: Midwives and Birth Centers discusses barriers regarding the utilization of certified nurse midwives (CNMs) and birth centers due to issues such as payment policies and scope of practice. The 2024 article The Availability of Midwifery Care in Rural United States Communities reports that over half of the surveyed rural hospitals stated they did not have available midwifery care with certified nurse-midwives in their communities.

Educational tracks for the maternal health workforce are also critical. According to the 2025 article Pregnancy-Care Intentions and Practice among Family Medicine Physicians: Residents, Obstetric Fellows, and Fellowship Alumni, family medicine (FM) residents who complete obstetrics fellowships are more likely to intend to provide maternity care, but few FM residents complete obstetrics fellowships. Understanding and Overcoming Barriers to Rural Obstetric Training for Family Physicians suggests the need to promote collaboration between family medicine and other obstetric practitioners while retaining and supporting family medicine obstetric faculty.

What other barriers and issues affect rural maternal health?

Rural maternal health is impacted by a number of issues, including but not limited to social determinants of health (SDOH), transportation barriers, intimate partner violence, and substance use.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) have negative impacts on maternal health and researchers have identified links between the SDOH and obstetric outcomes. Social determinants that may disproportionately affect rural women include insurance status, educational attainment, and income level. Public health agencies continue to develop tools to understand the impacts of SDOH on maternal health. For more information on SDOH, see our guide Social Determinants of Health for Rural People.

Transportation barriers contribute to difficulty in accessing maternal health services. Many women in rural areas must drive significant distances to see a maternal healthcare provider, which can contribute to missed appointments, forgone healthcare, or giving birth in an area without comprehensive services. Dual Barriers: Examining Digital Access and Travel Burdens to Hospital Maternity Care Access in the United States, 2020 states that nearly 40% of rural communities are located more than 30 minutes away from their closest maternity hospital unit, as well as having higher poverty and uninsurance rates. See our guide Transportation to Support Rural Healthcare for more information on the connection between rural healthcare and transportation.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has a disproportionate impact on rural women as well as pregnant and postpartum women. According to Rural/Urban Differences in Rates and Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse Screening among Pregnant and Postpartum United States Residents, rural women had higher rates of perinatal IPV at 4.6% compared to 3.2% of urban women. Rural women were also less likely to be screened for IPV, with probabilities of not receiving IPV screening at 21.3% for rural women and 16.5% for urban women. See our guide Violence and Abuse in Rural America for more information on IPV in rural areas.

Substance use can have negative impacts on maternal health for any woman, but rural women are specifically challenged in terms of accessing rehabilitation care and potentially experiencing stigma in their smaller communities. Programs such as Moms IMPACTT (IMProving Access to Perinatal Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Care Through Telehealth and Tele-mentoring) look to reduce disparities in behavioral health and substance use care for rural women through telemedicine, a strategy outlined in the article A Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program to Address Rural and Medically Underserved Populations Using Telemedicine. Our Substance Use and Misuse in Rural Areas topic guide discusses this issue in more detail.

See the Rural Maternal Health Toolkit's Barriers to Improving Maternal Health for more information on potential maternal health issues and barriers.

What policies, programs, or models address challenges with affordability, accessibility, and quality of maternal health services in rural areas?

To improve access and affordability of maternal health, many states have extended Medicaid coverage for postpartum care up to 12 months. Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker tracks these policy changes. Expanding Medicaid coverage to include doula care is another effort to improve maternal health. Doula Services in Medicaid: State Progress in 2022 explores state approaches to doula care, which can be particularly important for underserved communities who see higher rates of maternal morbidity and mortality. See State Medicaid Approaches to Doula Service Benefits for more information.

Another policy strategy is to provide paid family leave to help support maternal health during the postpartum period. According to Rural/Urban Differences in Access to Paid Sick Leave among Full-Time Workers, rural residents are nearly 10% less likely to receive paid sick leave than urban workers. Sick leave is often used in place of maternity or family leave for full-time workers. Having an employment situation without sick leave can therefore make recovery during the postpartum period more difficult. For more information on paid family leave by state, see State Paid Family Leave Laws Across the U.S., which tracks this issue.

In 2022, HRSA finalized a rule creating Maternity Care Target Areas (MCTAs), which are areas that experience a shortage of maternity healthcare professionals. The designation is determined by six criteria: 1) ratio of females aged 15-44 to full-time equivalent maternity care professionals; 2) percentage of females 15-44 with income at or below 200% of the federal poverty level; 3) travel time and distance to the nearest provider location with access to comprehensive maternity care services; 4) fertility rate; 5) the social vulnerability index; 6) a Maternal Health Index comprising prepregnancy obesity, prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, prenatal care initiation in the first trimester, cigarette smoking, and a behavioral health factor. These criteria will be used to create a composite score of 0 to 25 to indicate extent of need. The intent in creating this designation is to allow for direct federal support for maternity healthcare assistance to these target areas.

Telehealth policies are another avenue to improve maternal health access in rural areas. A CMS report notes that helpful strategies include expanding remote monitoring to help with addressing gestational diabetes, increasing access to virtual consultation with specialists, and virtual training and quality improvement programs such as Project ECHO. The Rural Monitor article, MotherToBaby Gives Rural Pregnant and Breastfeeding Moms 'Fingertip Access' to Exposure Experts, discusses using technology to provide rural mothers with free and confidential information via live chat, text, phone, and email services. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) created the UAMS Institute for Digital Health & Innovation (IDHI) High-Risk Pregnancy Program, which utilizes telehealth to improve access to care and maternal/infant healthcare outcomes.

The CDC Levels of Care Assessment Tool (CDC LOCATe) is an important assessment tool to help ensure that pregnant women and infants receive risk-appropriate care by assessing the level of care and distribution of staff and services available at different birthing facilities. Relatedly, in 2023, CMS implemented a "birthing-friendly" hospital and health system designation which indicates whether a hospital participates in a statewide or national perinatal quality collaborative program and implements evidence-based quality improvement programs to improve maternal health.

Policies that support the postpartum period as mothers return to work are also necessary for maternal and infant health. The 2023 report Changes in Policy Supports for Healthy Food Retailers, Farmers Markets, and Breastfeeding Among US Municipalities, 2014–2021: National Survey of Community-Based Policy and Environmental Supports for Healthy Eating and Active Living (CBS-HEAL) discusses supportive breastfeeding policies, such as providing maternity leave and space and breaktime to pump breast milk upon returning to work. The report finds that 31% of rural municipalities had some type of paid maternity leave in 2021 versus 41.2% of their urban peers, and 42.3% of rural municipalities provided breaktime and space to pump breast milk versus 55.4% for urban.

Ensuring educational opportunities for the rural maternal workforce in training helps to develop the workforce long-term. HRSA's Rural Residency Planning and Development Program offers a Maternal Health and Obstetrics Pathway that can support the development of obstetrics-gynecology rural residency programs, family medicine rural residency programs, or rural-track programs with enhanced obstetrical training. HRSA also has a Maternity Care Nursing Workforce Expansion (MatCare) Program to support training of nurse midwives. The 2025 article Rural Resource: Availability of Obstetric Simulation Training by State discusses availability of simulation training and continuing medical education (CME)/distance learning opportunities for hospitals with or without obstetric units, improving quality of care for potential maternity patients.

There are also federal and state programs that help reduce maternal health disparities in rural areas. The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) supports pregnant women and parents with young children who live in communities with greater risk and barriers to achieve positive maternal and child outcomes. Home visitors support healthy pregnancy practices, provide information on breastfeeding and safe sleeping, and offer other supportive activities.

The Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies (Rural MOMS) Program is aimed at increasing access and improving outcomes for rural mothers and infants through service aggregation and appropriate care, finding network approaches to care coordination, leveraging telehealth and specialty care, and establishing financial sustainability.

The 2023 Rural Monitor article In a Maternity Desert, a New Kind of Home Visitation Program Brings Care to At-Risk Mothers provides an overview of Project Swaddle, a community paramedic program focused on rural maternal health. Project Swaddle offers education, support, and medical care to perinatal women in rural Indiana.

Boosting Maternity Care in Rural America from the National Conference of State Legislatures discusses state and federal initiatives aimed at improving rural maternal healthcare. For more program examples and initiatives, see maternal health and prenatal care models and innovations.

What other resources are available to address maternal health?

California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative Quality Improvement & Toolkits – Aims to address the leading causes of preventable death in pregnant and postpartum women and to reduce harm to women and infants by educating on the overuse of obstetric procedures.

Better Maternal Outcomes Rapid Improvement Network – Provides resources and tools to advance high-quality maternal care, improve population health, enhance quality improvement, and create collaboration opportunities. From the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI).

Postpartum Toolkit – Supplies educational resources related to postpartum care. Focused on topics such as long-term weight management, pregnancy complications, reproductive life-planning, reimbursement guidance, and a sample postpartum checklist providers can use with their patients. From the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

HHS Office on Women's Health – Provides resources and programs for women related to reproductive and maternal health as well as disease and general wellness.

Rural Maternal Health Toolkit – Presents rural communities with resources and programs aimed at improving maternal health outcomes. Includes program models and resources for implementation, evaluation, funding, and sustainability.

Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) – Engages in technical assistance and capacity building to assist healthcare facilities with maternal health quality improvement. Provides patient safety bundles, resource kits, and resources.