Violence and Abuse in Rural America

If you are experiencing abuse and are seeking help, please contact one of these hotlines:

- National Sexual Assault Hotline

800.656.4673 - National Domestic Violence Hotline

800.799.7233 -

National Human Trafficking Hotline

888.373.7888

Violence and abuse are critical problems in the United States. Their effects in rural America are often exacerbated by limited access to support services for victims, family connections with people in positions of authority, distance and geographic isolation, transportation barriers, the stigma of abuse, lack of available shelters and affordable housing, poverty as a barrier to care, and other challenges. Those who suffer from abuse are often isolated and disconnected from healthcare and social service providers, without an understanding of how to access assistance. On the other hand, victims who live in small communities may be acquainted with healthcare providers and law enforcement officers, but reluctant to report abuse, fearing that their concerns will not be taken seriously, their confidentiality will not be maintained, their reputations may be damaged, or that they may incur even more abuse because the people causing them harm may be closely aligned with those who would otherwise offer protection. Another challenge for victims of domestic violence is financial dependence, which limits their ability to leave an abusive situation, particularly in rural communities with very limited resources for relocation, especially secure locations. It is difficult in small communities to keep the locations of shelters private.

As a best practice, community organizations can employ domestic violence and sexual assault (DV/SA) advocates who have completed training curricula developed by recognized industry leaders such as RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network). DV/SA advocates have experience working with survivors of violence and can assist them to identify ways to increase personal safety while assessing their particular risks. Advocates also maintain confidentiality and typically offer 24/7 services and support in-person, remotely by text or phone, and in some cases at a secure location of the survivor's choosing, known as mobile advocacy.

Violence and abuse prevention and response are not the domain of one specific community group. Building partnerships between healthcare organizations and community-based services can lead to increased staff engagement, comprehensive responses for survivors, and bi-directional referral protocols for patients and clients.

This guide addresses abuses that may take place in rural communities, including:

- Domestic violence, also known as intimate partner violence (IPV)

- Sexual violence, including rape, assault, and abuse

- Abuse, neglect, and exploitation of people, such as children, older adults, and people with disabilities

- Bullying, harassment, and stalking

- Assault

- Homicide

- Human trafficking

For information about suicide, see the Rural Mental Health topic guide.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How prevalent is violence and abuse in rural America?

- How does violence and abuse affect health outcomes for rural populations?

- How does rural healthcare access affect current victims and survivors of abuse?

- What services do rural victims of violence need?

- What can rural communities do to prevent violence and abuse?

- How does human trafficking affect rural communities?

- What are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and how might they affect the health of rural people?

- How does child abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence in rural communities compare to cases in urban areas?

- What are the barriers to addressing rural domestic violence/intimate partner violence?

- How does living in a rural community impact sexual assault victims and survivors?

- What concerns are there for protecting rural older adults from violence, neglect, and financial abuse?

- What is the impact of a rural setting on victims of harassment, stalking, and bullying?

- What are strategies that rural healthcare providers can use to identify and support victims of abuse?

- What is trauma-informed care and how does it support survivors of violence and abuse?

How prevalent is violence and abuse in rural America?

According to 2024 federal crime statistics, violent crime rates in nonmetropolitan counties were lower than the national average.

| Violent Crime Type | U.S., total | Metropolitan Statistical Areas | Cities Outside Metropolitan Areas | Nonmetro counties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent Crime | 359.1 | 376.1 | 337.8 | 194.6 |

| Murder and non-negligent manslaughter | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 3.7 |

| Rape | 37.5 | 36.9 | 50.3 | 35.5 |

| Robbery | 60.6 | 68.3 | 21.6 | 5.9 |

| Aggravated Assault | 256.1 | 265.9 | 261.0 | 149.4 |

| Source: 2024 Crime in the United States, CIUS Estimations File: Table 2, Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer: Documents & Downloads | ||||

However, crime statistics may be artificially low since not all crimes are reported and not all allegations can be substantiated. The Bureau of Justice Statistics' Criminal Victimization, 2024 notes that in 2024 only 47.9% of violent crimes were reported to the police. Reasons for not reporting a crime include fear of reprisal or getting the offender in trouble, believing the police would not or could not help, and feeling the crime is too trivial or personal. It is important to note the percentage of rape or sexual assault victimizations reported to police decreased from 2023 to 2024, from 46.0% in 2023 to 23.6% in 2024.

See the 2020 National Crime Victimization Survey Factsheet for more information on reporting, data results from the NCVS, and survey details. Access additional data through the National Crime Victimization Survey Data Dashboard. See United States Health and Justice Measures of Sexual Victimization for more information on the different ways the federal government measures sexual victimization.

One common type of violence and abuse is domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collects national- and state-level data on intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking. In a March 2015 policy brief, the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services called on the CDC to include in the NISVS a geographic variable showing level of urbanization to represent how IPV affects rural residents.

Victims of domestic violence can be of either sex though women are more often impacted than men. A 2022 CDC fact sheet reports that 41% of women and 26% of men experience IPV during their lifetime. Domestic violence often escalates into repeated and more violent abuse. In 2021, 34% of female murder victims were killed by an intimate partner. For information on rates of male victimization, see the CDC's Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, and Stalking Among Men.

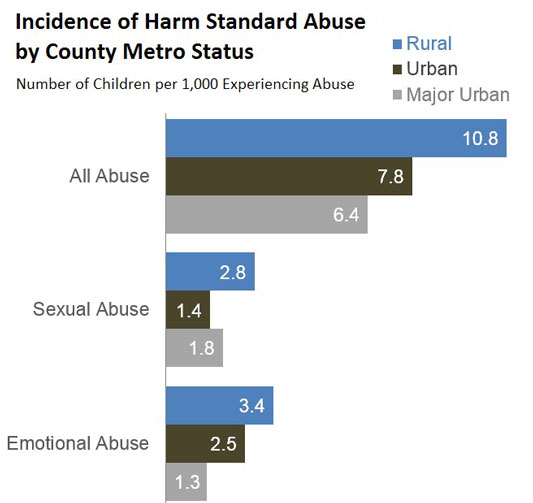

Neglect and abuse of children also impacts rural communities. The Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4) from the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) states that the reported incidence for all categories of maltreatment except educational neglect was higher in rural counties than in urban counties, with rural children being almost twice as likely to experience maltreatment, including overall abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. However, the report's authors caution that this difference may not actually indicate a higher rate of abuse in rural areas but may be due to higher survey response rates in rural areas, differences in socioeconomic status and family size, or other factors. This is also reflected in the 2021 article Rural Differences in Child Maltreatment Reports, Reporters, and Service Responses that found maltreatment reporting rates were higher in rural areas, but rates of confirmed maltreatment were similar in rural and urban areas.

The Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine's 2014 report New Directions in Child Abuse and Neglect Research indicates a need for cooperative approaches in recognizing and reporting child abuse and neglect, particularly in geographically isolated areas. Child Maltreatment 2023 represents national data on child abuse and neglect. For more information about working with children affected by abuse or neglect, see Promising Futures.

How does violence and abuse affect health outcomes for rural populations?

Violence and abuse lead to short-term and long-term physical and psychological injury for both rural and urban victims. However, barriers to accessing healthcare, limited access to support services such as domestic violence or sexual assault advocacy, and the lack of specialized healthcare responders paired with geographic isolation or limited daily contact with others can limit the ability of rural survivors to seek treatment for injuries. For example the 2021 study Rural Availability of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners found that consistent coverage of certified SANEs is limited in rural areas of Pennsylvania, suggesting that sexual assault victims and survivors may receive lower quality treatment compared to urban residents.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women's Health, immediate effects of violence for survivors can include:

- Bruises, cuts, and broken bones

- Concussion and traumatic brain injury

- Internal injury to organs

- Pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding

- Unwanted pregnancy

- Infectious diseases, including HIV and HPV

- Sleep problems

Some of these injuries require medical examination and treatment, which may be challenging to access in remote or rural areas. Left untreated, these injuries can lead to serious infection or long-term health problems. In addition, children and older adults who are abused or neglected are at risk of traumatic brain injury and may not receive necessary follow-up care.

According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2016/2017 from the CDC, people who experienced sexual violence, stalking, or IPV experienced higher rates of various health conditions such as asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain and headaches, and difficulty sleeping compared to people who had no history of abuse and violence.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can lead to poor health outcomes in adulthood. Information about the effects of ACEs on health status and health outcomes is included in the FAQ What are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and how might they affect the health of rural people?

How does rural healthcare access affect current victims and survivors of abuse?

Victims and survivors of abuse in rural areas often struggle to find immediate and continuing access to healthcare and social services. When services are lacking, victims may be reluctant to report abuse due to the possibility that it will just make their situation worse.

Isolation due to geographic location is also an issue for abuse victims. Distance to clinics and hospitals and lack of public transportation may make prompt access to healthcare difficult. Additionally, lack of providers plays a role in the overall care of victims and survivors of abuse, with limited funding and higher per capita costs for social services leaving limited resources for specialized staff to help with violence and abuse support. For more on issues related to accessing rural healthcare, see the Healthcare Access in Rural Communities topic guide.

When services are lacking, victims may be reluctant to report abuse due to the possibility that it will just make their situation worse.

Examples of innovative programs to support victims and survivors of abuse include the Massachusetts Department of Public Health TeleSANE Center, Kingsville End Domestic Violence Task Force, and the Butte Child Evaluation Center. Opening Our Doors: Building Strong Sexual Assault Services in Dual and Multi-Service Advocacy Agencies offers resources for developing rural domestic violence and sexual violence initiatives through organizational partnerships.

What services do rural victims of violence need?

Social Services

The National Rural Health Association policy brief Rural Community Violence: An Untold Public Health Epidemic recommends that rural communities support victims of violence by offering or establishing:

- Employment and vocational training

- Counseling

- Violence prevention programs in clinical settings

- Awareness campaigns promoting prevention and intervention programs

- Anti-bullying and mentoring programs in schools

Transportation, emergency housing, and employment are essential for rural victims to leave abusive living situations and become self-sufficient. Unfortunately, rural victims may face barriers to accessing services, including a lack of broadband internet and a dearth of available human services. For more information on the challenges of accessing human services in rural areas, see the FAQ How is the provision of human services different in rural areas? on our Human Services to Support Rural Health topic guide. See the Rural Services Integration Toolkit for more information on efforts to increase access to services for rural communities.

The NRHA policy brief notes that violence takes many forms, including murders and suicides, robberies, and bullying. The policy brief offers recommendations for preventing and responding to rural violence, including:

- Increasing awareness of the problem through media outlets

- Advocating for the allocation of resources at the local level

- Establishing funding partnerships to expand community resource centers

- Establishing and supporting batterer intervention programs

See the Rural Emergency Preparedness and Response Toolkit for more information on planning for and responding to emergency situations including mass casualty events occurring from violent events.

Advocacy and Legal Services

Abuse victims may need specially-trained advocates to help them navigate the legal system or locate and use local social service and support programs. Rural victims may need these services even more because of close-knit community and criminal justice systems, often including familial relationships that can create issues of confidentiality and safety for victims. Advocates can:

- Provide expertise on victim safety and emotional support

- Help navigate financial systems to retain or regain assets and establish power of attorney, guardianship/conservatorship, or custody

- Assist with restraining or protective orders

- Support survivors in enrolling in health insurance and connect or accompany them to health services

- Assist with applying to state crime victims compensation and reparations programs

- Provide referrals to local agencies providing emergency aid including food pantries and clothing closets

The National Domestic Violence Hotline Provider Search can be used to locate local assistance providers including legal services. The American Bar Association offers a no-cost Find Legal Help tool that connects people to professionals in their state. Many state sexual assault and domestic violence coalitions can assist survivors with accessing legal services. The Legal Services Corporation also provides a search tool to find legal aid in each state. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center offers The Advocate's Guide: Working with Parents of Children Who Have Been Sexually Assaulted.

Another consideration for healthcare-specific legal needs in rural communities is a medical-legal partnership. Such partnerships provide onsite legal aid in a medical setting (such as a clinic, hospital, or dental practice), and allow for a safe and immediate space for people who need help. More information about this type of partnership is available in the October 2016 Rural Monitor article, Bringing Law and Medicine Together to Help Rural Patients, and through the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership.

What can rural communities do to prevent violence and abuse?

Rural communities can band together to prevent and respond to violence and abuse through a Coordinated Community Response (CCR). This collaborative effort among healthcare providers, community groups, faith-based organizations, schools, criminal justice, and social service agencies allows for a broad opportunity to stop violence before it starts. Resources for Advocates & Educators from the National Sexual Violence Resource Center can promote cooperation between agencies and the larger community.

Partnerships between healthcare providers and domestic/sexual violence advocacy programs are a powerful way to ensure that survivors' health needs are being met, and to help promote prevention. Futures Without Violence offers an evidence-based prevention and intervention resource called "CUES" to help providers educate their patients about the connections between IPV and human trafficking and their health, engaging them in strategies to promote wellness and safety. "CUES" stands for:

Confidentiality: Knowing your state's reporting requirements, sharing confidentiality requirements with your patients, and always seeing patients alone for part of every visit so that you can bring up relationship violence safely.

Universal Education and Empowerment: Whether or not a patient discloses abuse, providing patients with information about the impact of relationships on health and letting the patient know they can share their relationship concerns with you.

Support: In the case of domestic violence disclosures, referring patients to local domestic/sexual violence partner agencies or national hotlines, and sharing health promotion strategies and a care plan that takes surviving abuse into consideration.

The Human Services to Support Rural Health topic guide has resources to help address child welfare and discusses the use of Family Resource Centers to assist those in rural communities.

Some communities sponsor programs for people who want to change their own violent or controlling behavior. For those interested in establishing an abuser treatment program in their region, more information is available at:

- Minnesota Program Development: The Duluth Model

- Emerge: Counseling and Education to Stop Domestic Violence

The CDC offers a variety of resources designed to bolster community support for violence prevention programs. These include:

- Prevention Resources for Action – Strategies representing the best evidence to prevent or reduce violence and to improve well-being of communities. Topics covered include Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Child Abuse & Neglect, Community Violence, Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, and Suicide.

- Essentials for Childhood: Creating Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and Environments for All Children – Strategies to prevent child abuse and to help create safe neighborhoods and communities

- Using Essential Elements to Select, Adapt, and Evaluate Violence Prevention Approaches – Intended for practitioners, but may be useful for funders and people who provide training and technical assistance

For communities lacking local resources to address violence and abuse, national resources are available. The National Domestic Violence Hotline offers real-time support to survivors of domestic violence through trained advocates who are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Preventive services are also available through their Love is Respect service. This program aims to disrupt and prevent unhealthy relationships and intimate partner violence by offering information, support, and advocacy to young people between 13 and 26 via phone, text, and live chat.

See the Rural Emergency Preparedness and Response Toolkit for more information on planning for and responding to emergency situations.

How does human trafficking affect rural communities?

The Administration for Children & Families defines trafficking as the use of force, fraud, or coercion to provide labor or commercial sex. Additionally, inducing commercial sex with a minor is trafficking even absent force, fraud, or coercion. According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) resource Human Trafficking 101, human traffickers exploit victims through promises of employment, a better life, manipulation, threats of violence, and imposed financial debt.

Common barriers that prevent victims from seeking help include physical, economic, or legal factors; fear of abuse or violence; distrust of government or law enforcement; language barriers; not identifying as a victim; and lacking an awareness of available resources. The American Psychological Association's Report of the Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls notes that in the United States, labor sectors in which human trafficking is most often identified are also those that most frequently employ female migrant workers, such as the service industry, domestic service, home healthcare and nursing homes, sex work, and agriculture. The study suggests that widespread poverty in some countries leads migrant women into employment situations in the U.S. that may make them susceptible to trafficking.

Research on human trafficking points to healthcare as a critical area of intervention. According to the 2017 article Health Care and Human Trafficking: We are Seeing the Unseen, 68% of human trafficking survivors had contact with a healthcare provider while they were being trafficked, though they may not have reported their victimization.

The Rural Monitor article "It's on Us": Healthcare's Unique Position in the Response to Human Trafficking discusses ways healthcare providers can recognize and address trafficking. To provide a quick-reference tool, the American Hospital Association created a human trafficking card that lists 10 red flags for providers to be aware of when working with patients who may be victims.

The Health Partners on IPV + Exploitation, an initiative led by Futures Without Violence, works with community health centers to support survivors and those at risk of intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and exploitation, and to support prevention efforts. The Network is a National Training and Technical Assistance Partner (NTTAP) funded by HRSA's Bureau of Primary Health Care.

The Office of Trafficking in Persons offers an online training module, SOAR to Health and Wellness Training, to build capacity to engage human trafficking victims at the community level.

For data on human trafficking, see the national and state statistics from National Human Trafficking Hotline.

What are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and how might they affect the health of rural people?

The term adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) was coined in a 1998 study of health-related behaviors and childhood adversity experienced in the first 18 years of life. The 2018 policy brief Exploring the Rural Context for Adverse Childhood Experiences from the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services defines ACEs as:

“any form of chronic stress or trauma (e.g., abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction) that, when experienced during childhood and adolescence, can have both short- and long-term impacts on an individual's development, health, and overall well-being.”

Examples of ACEs include:

- Verbal, physical, and sexual abuse

- Physical or emotional neglect

- Having family members who are mentally ill, have substance abuse issues, or are incarcerated

- Witnessing family violence

- Having parents who separate or divorce

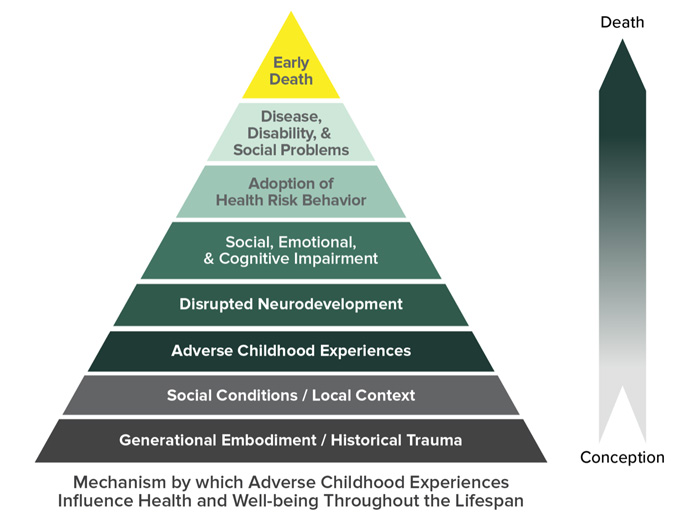

The CDC offers a visual representation of the cascading mental and physical health impacts of ACEs, with each tier of the pyramid building on the damaging effects of the layers below:

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau's 2022 brief Rural Children’s Health and Health Care found that 7 of the 9 ACEs studied were more common for rural children than urban children. ACEs can have a multi-generational effect; in a 2020 Children and Youth Services Review article, researchers found that children raised by caregivers who reported 4 or more ACEs were 3 times more likely to develop depression and/or anxiety. Positive childhood experiences (PCEs) are supportive environments outside the home that may reduce the negative outcomes associated with ACEs. Another article, Safe, Stable, and Nurtured: Protective Factors against Poor Physical and Mental Health Outcomes Following Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) looks at positive factors that can offset ACEs, including growing up with a protective adult in a safe home, finding that protective factors may mitigate negative physical and mental health outcomes associated with ACEs.

Additionally, children may fall under the category of secondary victim, defined as an individual suffering negative experiences as an indirect consequence of a crime. In cases where a parent was the victim of more severe abuse, children who are witness to domestic violence or sexual assault may not receive adequate victim support as the focus of investigative efforts are the primary victim.

ACEs and their impact on health and well-being can be prevented. For more information, see the CDC's 2019 publication Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Prevention: Resource for Action and the Rural Monitor article Confronting Adverse Childhood Experiences to Improve Rural Kids' Lifelong Health. For information on the role of schools in addressing ACEs see the FAQ How can rural schools work to address and prevent adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)? on our Rural Schools and Health topic guide.

How does child abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence in rural communities compare to cases in urban areas?

Incidence of child abuse and neglect are often associated with low socioeconomic factors common in rural areas. Family stress, caused by conditions such as poverty, substance abuse, and health problems may add to the incidence of child abuse and neglect by caregivers. The CDC's Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention: Resource for Action: A Compilation of the Best Available Evidence notes that children in low socioeconomic status (SES) families experience child abuse and neglect at 5 times the rate of children in families with a higher SES. For more information on how socioeconomic factors disproportionately impact rural residents, see our Social Determinants of Health for Rural People topic guide.

In rural communities, child abuse or neglect may be underreported due to isolation and geographic remoteness, lack of social services or other support programs, lack of or limited foster care or emergency housing, and social stigma for survivors.

Rural children can be victims of or witnesses to violence both inside and outside the home. A 2023 report from the CDC found the homicide rate for infants is 9.31 per 100,000 for those born to rural mothers compared to those born to urban mothers at 6.76. According to Rural Children’s Health and Health Care 4.2% of rural children have been victims or witnesses to neighborhood violence, compared to 4.1% in urban areas. This report also notes that 7.9% of children from rural areas reported witnessing parental violence, compared to 5.1% of children from urban areas.

For national data on child abuse and neglect and state-level information, see the Child Maltreatment 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. For more on comparing abuse between rural and urban areas, see the 2021 article Rural Child Maltreatment: A Scoping Literature Review.

What are the barriers to addressing rural domestic violence/intimate partner violence?

Access to healthcare, prevention, social and human services, and protection services in rural communities is often limited based on funding and availability of a healthcare workforce trained in domestic violence intervention. Despite this limitation, healthcare workers hold a key position in serving victims of IPV, as discussed in the 2020 policy brief Rural Versus Urban Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence-Related Emergency Department Visits, 2009-2014. The brief notes that:

“Recent data indicate prevalence might be similar in rural and urban populations, but hospitalizations related to IPV are greater in rural areas, suggesting difficulty accessing preventive services to intervene before violence escalates. Areas with few services are also associated with higher levels of IPV-related homicide.”

The 2024 policy brief Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Committees: Perspectives from Key Informant Interviews also found that access to IPV-related support services and healthcare can be a barrier. The brief also notes that stigma and existing risks for marginalized groups serve as barriers to addressing IPV. Pregnant and postpartum residents in particular are at risk for IPV in both urban and rural areas. However, the 2023 study Rural/Urban Differences in Rates and Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse Screening among Pregnant and Postpartum United States Residents found that rural residents had both a higher prevalence of IPV and were at a higher risk of not being screened for IPV in a healthcare setting compared to urban residents. For more on rural challenges in maternal healthcare, see our Rural Maternal Health topic guide.

For more on using community resources to address domestic violence, see Ending Domestic Violence: How a Rural Texas Town Built a Support Net for Victims in The Rural Monitor.

How does living in a rural community impact sexual assault victims and survivors?

In rural communities, victims and survivors of sexual violence may face challenges accessing support services and care, including limited transportation options, geographic isolation or remoteness, and limited phone service. Addressing rural sexual violence may be challenging due to the lack of anonymity in close-knit communities in which an abuser may share the same network as law enforcement and due to rural cultural attitudes of self-reliance, independence, and resistance to outside intervention.

Disparities in care for sexual assault can be found as early as the forensic examination survivors undergo. The 2016 Government Accountability Office report Sexual Assault: Information on Training, Funding, and the Availability of Forensic Examiners notes that all six states consulted for the report did not have enough examiners to meet their needs, especially in rural areas. Similarly, the 2023 study Emergency Department Preparedness to Care for Sexual Assault Survivors: A Nationwide Study found that sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) are more likely to be available in urban areas than rural ones. The presence of a SANE can increase the quality of care received by the patient. Survivors attended by SANEs were more likely to receive trauma-informed care and continued support through follow-up resources.

Community conversation and cooperation are important factors in establishing and maintaining survivor support. Resources that address rural community responses to sexual violence include Stopping the Stigma: Changing Public Perceptions of Sexual Assault in Rural Communities and Safe Havens' Rural Communities Responding to Sexual and Domestic Violence.

What concerns are there for protecting rural older adults from violence, neglect, and financial abuse?

Rural older adults who suffer violence and abuse have special considerations when it comes to the need for response, protection, and support, both as victims and survivors. Health concerns associated with aging, such as physical limitations and dementia, as well as the risk of limited social networks make older adults more susceptible to physical neglect and abuse, personal neglect, and financial coercion. Victims who have physical and cognitive disabilities may need advocates to help them access specialized services, resource materials, or interpret legal proceedings. The Administration for Community Living (ACL) provides prevention strategies information. See the 2024 brief Variation in Elder Abuse State Statutes by State Level of Rurality to learn more about characteristics of elder abuse statutes' definitions and reporting requirements across states.

Futures Without Violence offers an Elder Resources page and the Aging With Respect safety card that healthcare providers and human service agencies can make available. The card contains information about abuse of older adults and exploitation, healthy and unhealthy relationships, and health impacts of those relationships. Futures Without Violence recommends using this safety card with the CUES universal education intervention.

ACL's blog post Elder Abuse: A Public Health Issue that Affects All of Us recognizes abuse of older adults as a public health issue, noting that approximately 10% of adults over 60 have experienced abuse, neglect, and/or financial exploitation. The authors note that communities can support older adults and look out for signs of abuse, citing this list of 12 actions that communities can take to prevent elder abuse from the National Center on Elder Abuse.

The Department of Justice's Elder Justice Initiative developed a resource guide in conjunction with its 2018 Rural and Tribal Elder Justice summit. In addition, the 2018 Rural Monitor article Late Life Domestic Violence: No Such Thing as "Maturing Out" of Elder Abuse discusses local interventions to address abuse of older adults and violence. The Elder Abuse Guide for Law Enforcement (EAGLE) offers a helpful community resource database for older adults that is searchable by ZIP code.

What is the impact of a rural setting on victims of harassment, stalking, and bullying?

According to Perspectives on Civil Protective Orders in Domestic Violence Cases: The Rural and Urban Divide, a study showed that rural women who were granted protection orders were more likely to fear future harassment or harm than their urban counterparts. The author suggests that reasons for this may include:

- Geographic isolation

- Lack of community services

- Higher percentage of rural women married to the people named in the protection orders

- Rural women more likely to be in long-term relationships with their abusers, and more likely to have children in common with them

Bullying, primarily associated with school age children, can be particularly harmful in a rural community where access to support services impedes the administrator's ability to intervene or solve the problem effectively. The 2024 brief Student Reports of Bullying: Results from the 2022 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey found that 23.8% of students in rural schools reported being bullied in the 2021-2022 school year. 23.0% of those rural bullied students reported being bullied online or by text message and 12.1% report negative effects to their physical health as a result of the bullying. Geographic isolation does not affect the bully's ability to harass the victim through electronic means.

Resources to help communities prevent bullying are available at StopBullying.gov. For an example of partnerships between healthcare providers and law enforcement to address bullying, see the 2018 Rural Monitor article Together We Can Be Bully Free: CAH and Law Enforcement Address Peer Victimization through School-Based Program.

What are strategies that rural healthcare providers can use to identify and support victims of abuse?

Rural healthcare providers often play many roles with little specific training to support victims of violence. There is a need for integration of screening and counseling for victims of violence and abuse in primary care practices. A March 2015 policy brief from the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services suggests that routine screening for signs of violence or abuse should become standard practice for primary care providers and nurses. These professionals should be familiar with the existing resources in their communities, including sources of domestic violence support such as churches, faith-based providers, and community organizations.

Screening older adults for violence, neglect, and abuse is important since they may be reluctant or unable to report being victimized. According to the National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA), abuse of older adults is underreported. In response to this issue, NCEA offers a summary of screening tools available to health professionals. In addition to these resources, the University of Maine Center on Aging offers a screening protocol and tool for older adults that has been tested and implemented in rural primary care practices.

Routine screening for intimate partner violence and referrals to support services for victims is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for all women of childbearing age. In spite of this recommendation, a 2023 study found that rural women are more likely to experience intimate partner violence and that rural residents are less likely to be screened for violence and abuse when compared with urban residents. An October 2016 American Family Physician article, Intimate Partner Violence, provides recommendations for routine screening for domestic violence and includes examples of screening tools, as well as tips for discussing this issue with patients. IPVHealth.org is a resource that healthcare providers can use to learn more about the health impact of violence and abuse. It offers tools and resources for establishing a partnership between domestic violence agencies and health settings and describes how healthcare settings can move beyond screening for intimate partner violence using the CUES universal education approach. A related project, IPVHealthPartners.org offers a toolkit, Prevent, Assess, and Respond: A Domestic Violence Toolkit for Health Centers & Domestic Violence Programs, based on the experiences of successful community health center/domestic violence agency partnerships.

Healthcare facilities can also help raise awareness of services available by placing brochures and posters in exam rooms and restrooms. For example, the Georgia Coalition Against Domestic Violence (GCADV) offers downloadable tip sheets and brochures. Futures Without Violence offers more than 50 multilingual safety card resources for a range of settings and patient populations that healthcare providers can make available to patients. The National Domestic Violence Hotline offers downloadable posters and educational materials that are free to distribute.

Facilities and providers can increase access to services for domestic violence, sexual assault, or other violence by providing a safe place for victims to meet with service providers (such as counselors or sexual assault nurse examiners). This may include a telehealth connection to counselors or other crisis intervention professionals located at a distance for those in particularly rural and remote areas.

The Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) in the U.S. Department of Justice provides grants to communities, medical providers, and other service providers who are working to implement strategies to protect women and their children who are victims of violence and abuse. The Office sponsors the Rural Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Program, which provides targeted funding for rural communities and several funding programs for tribal communities. OVW provides technical assistance to communities and has created two versions of the National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations: Adult/Adolescent and Pediatric, through the SAFEta Project.

One organization successfully providing services for victims of sexual assault at the local level includes Canyon Creek Services in rural Utah. For more information on the role of healthcare providers in responding to domestic and intimate partner violence, see the 2018 Rural Monitor articles Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: Some Do's and Don'ts for Health Providers and The Ruralness of Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: Prevalence, Provider Knowledge Gaps, and Healthcare Costs.

For more information on identifying and addressing human trafficking, including tools available to practitioners and administrators, see the FAQ How does human trafficking affect rural communities?

What is trauma-informed care and how does it support survivors of violence and abuse?

The Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center defines trauma-informed care as an approach to healthcare that considers a patient's complete life situation, including past and present experiences involving trauma, to improve health outcomes and patient wellness. According to the center, "Trauma-informed care shifts the focus from 'what's wrong with you?' to 'what happened to you?'"

A 2019 Center for Health Care Strategies blog post on a trauma-informed response to substance use disorder in rural Tennessee notes that trauma-informed care:

“represents a paradigm shift toward a model of health care that values relationships over efficiency, and quality over quantity. It acknowledges that a lack of empathy and understanding between patient and provider poses a serious barrier to care.”

Rural survivors face additional barriers caused by the stigmas associated with abuse, IPV, and sexual violence and because of healthcare access issues. Trauma-informed care aims to overcome these barriers by making healthcare welcoming and safe for survivors and victims to seek help.

Organizations like Trauma Informed Oregon (TIO) offer resources directed to state-level healthcare and health-related organizations such as this Road Map to Trauma Informed Care. In a 2016 post to their blog, TIO details the experience of staff at the rural La Pine Community Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center, as they implemented TIC through consultation and staff training. In addition, an issue brief from the Center for Health Care Strategies describes Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation. Both pieces emphasize the importance of attending to staff needs and possible secondary traumatic stress among healthcare workers as the organization implements trauma-informed care.

For more information on healthcare responses to various types of trauma and healing, see the 2019 Rural Monitor article Rising from the Ashes: How Trauma-Informed Care Nurtures Healing in Rural America. In addition, the Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center offers more information to get started with trauma-informed care.