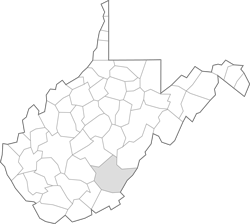

COVID-19 Community Task Force Utilizes Cross-Sector Response in Rural Greenbrier County, West Virginia

What Happened

The Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force in West Virginia formed in March of 2020 in response to the overwhelming impact that the global COVID-19 pandemic had on the community. The Task Force was chaired by West Virginia State Senator Stephen Baldwin and met multiple times a week for nearly two years to address issues related to the pandemic. Part of the Task Force's success can be attributed to lessons learned from the devastating floods that hit West Virginia in 2016 and involved the loss of life and shelter for many in the southeastern portion of the state. Those experiences created relationships in Greenbrier County that were further strengthened during the COVID-19 response. Julian Levine, Director of Community Engagement and Outreach (CEO) at the West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine (WVSOM) Center for Rural and Community Health (CRCH), observed the legacy of collaboration that the 2016 floods in rural Greenbrier County left, as stakeholders from different organizations came to the table ready to work together and share resources.

Levine was part of the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force from its inception. As Director of CEO for WVSOM CRCH, Levine works with rural communities to identify and develop collaborations for community-engaged research focused on community health improvements. In this role, Levine also leads a nonprofit partner, Greenbrier County Health Alliance (GCHA), on community projects. People from multiple sectors of the community worked together under this Task Force. Levine noted, crediting Senator Baldwin, that “communication, collaboration, and coordination” were the key factors in the Task Force's success. From sharing information to “digging in and rolling up their sleeves,” the COVID-19 response in Greenbrier County was a community-led endeavor.

WVSOM is a public institution and the largest medical school in West Virginia. Due to the medical school's resources and community focus, as soon as COVID-19 hit the community, CRCH offered support to the Greenbrier County Health Department (GCHD) in their pandemic response operations. Public Health 3.0 tasks health departments to act as the Chief Health Strategists in their community. The reality, however, is that health departments often have limited funding to cover a broad mission. It was extremely challenging for the small, rural GCHD to address the highly transmissible COVID-19 pandemic while continuing their typical functions and activities. WVSOM CRCH became involved and lent their support to the GCHD in response.

Initially, the GCHD requested support from CRCH with managing and coordinating data. The health department was experiencing a barrage of phone calls concerning COVID-19. Before vaccinations for COVID-19 were developed, many callers were inquiring if they could be placed on a waitlist to receive the vaccine once it became available. Levine noted that CRCH at WVSOM had access to resources such as scalable phone systems, software, expertise in information management, AmeriCorps volunteers, and WVSOM's in-house information technology department. These resources allowed them to develop a system to fairly field and organize the incoming community calls related to vaccines and pandemic questions. WVSOM, a partner institution of the West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI), had expertise and experience in working with communities to improve community health outcomes. This expertise proved instrumental in their success to support the COVID-19 response in Greenbrier County.

While WVSOM CRCH's involvement with the GCHD began with data support, the needs and response capacities shifted as the pandemic went on. Once vaccinations for COVID-19 were available, CRCH developed a hotline to assist in fielding calls from community members seeking vaccination appointments. The hotline project snowballed into helping GCHD coordinate vaccine scheduling and appointments, as well as assisting with the logistics of a months-long, large-scale, regional vaccination hub in the rural county. Alleviating pressure in areas where the GCHD was stretched thin was the main goal of CRCH's involvement in the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force response. Levine emphasized that CRCH was there to be a supportive resource for the GCHD and that so many organizations in the community deserve credit for the response effort. WVSOM, he noted, was not leading the response, but rather was “a small part of a really mighty effort.”

The Greenbrier County Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency (GCHSEMA) was another crucial leader in the COVID-19 response and vaccination effort. With GCHD spearheading public health and GCHSEMA directing disaster management, other capacities were made stronger. Other organizations highly involved in the effort included regional healthcare organizations such as the Robert C. Byrd Clinic, Rainelle Medical Center, Greenbrier Valley Medical Center, Greenbrier County Board of Education, State Fair of West Virginia, numerous community nonprofits, restaurants, businesses, and many others.

Planning

In 2016, prior to the pandemic, partners from multiple sectors in the community, including public health, business, healthcare, government, nonprofit, and education, came together to form a task force in response to multiple floods that wreaked havoc on the southeastern parts of West Virginia. The connections built during this response, as well as the lessons learned from the event, were still strong in the minds of people in Greenbrier County as the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect the community. This experience was a valuable guide for emergency COVID-19 response in the community. The task force model was adaptable and stakeholders from across sectors quickly mobilized resources. The Greenbrier County Local Emergency Planning Committee (LEPC), under GCHSEMA, meets regularly at the GCHD and invites community stakeholders, such as WVSOM CRCH, to take part in the continuous planning process.

Response

The Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force began meeting in March 2020 and continued meeting at least once a week, and up to 3 times a week, until February 2022. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the GCHD, like other health departments across the country, was required to immediately scale up their operations to coordinate a public health response. They worked tremendously long hours and had to constantly adjust processes as problems arose and the pandemic evolved — a cycle that did not break for over a year and a half. According to Levine, this increased level of duty is why it was critical, even on an individual level, for the community to step up to support the GCHD. The Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force's goal was to offer their expertise in support of GCHD, so that GCHD could continue to conduct their essential functions. CRCH could design infrastructure to handle data and information systems regarding vaccine scheduling, for example. While this was something GCHD could do, CRCH could not conversely vaccinate people in the community. Similarly, local businesses stepped up to provide food for the volunteers at the large-scale vaccination clinics – these acts of volunteerism took an additional burden off both GCHD and GCHSEMA that allowed them to maintain focus on critical response activities.

The Task Force also supported another cross-sector collaborative effort led by Greenbrier County Schools through a partnership with multiple organizations, including the Greater Greenbrier Long-Term Recovery Committee, a disaster recovery nonprofit founded during the 2016 floods. When schools shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in spring of 2020, the Greenbrier County Board of Education reached out to develop more surge capacity to arrange food services for students who were now attending school remotely. With children schooling from home, it was essential to develop a system for ensuring schoolchildren could continue to access federally reimbursable meals. The system had to accommodate both ordering and delivery logistics. This system also had to be developed quickly to cover gaps between the time in which the pandemic forced schools to close and when the state could implement a sustainable, larger-scale system. The Task Force worked with Greenbrier County Schools and created a system to ensure students received school meals while longer-term systems were put into place. Many similarly unique systems were developed through local partnerships for the small, rural area. Levine noted that the willingness to share power and the foresight to seek support from multiple stakeholders in the community contributed to a strong culture of collaboration during the response.

Recovery

Handling communications and information sharing is an important step in emergency response that carries into the recovery phase. After the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force held meetings to address pandemic response, notes from the meetings were disseminated widely. The minutes were sent out through the Task Force members' email lists, and they were published by local newspapers. Community members could then direct questions to any member of the Task Force to be shared at the next meeting. The “direct feedback loop” created through this process enabled the people in Greenbrier County to have access to real-time updates. Communication within the Task Force was centralized, but it was also made available to grassroots-level stakeholders in the community.

As a result of the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force response, WVSOM CRCH has a closer working relationship with GCHD. This partnership is beneficial to the area, as Levine's focus is on developing more infrastructure for community-based research and community health projects. Health departments around the country, noted Levine, are important avenues through which research is communicated. In Greenbrier County, GCHD, GCHSEMA, and the local hospitals, clinics, and healthcare organizations of different sizes worked together well before COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic strengthened these partnerships and activated stronger connections with businesses, nonprofits, and the school system in the community.

Success Factors

Task Force Model

Levine described the task force model as a resource to community response planning with the idea that every community will have different resources and organizations that can come to the table in an impactful way. Putting together a network where people communicate, collaborate, and coordinate in a systematic way allowed the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force to open its abilities for a successful response that amounted to more than the sum of its parts. WVSOM is a key resource to the Greenbrier County community. As an anchor institution, it possesses resources that can benefit the community, such as the power of information technology (IT) and people needed to undertake projects such as setting up a virtual phone system.

The State Fair of West Virginia was another key resource at play in the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force's response. GCHD did not have a large enough space to hold a mass vaccination clinic. The State Fair of West Virginia, however, opened itself up as a resource that allowed the rural community response to scale upwards in a way that was not previously possible. While every community may not have these specific resources, Levine noted that every community does have their own organizations that may be willing to contribute. Cross-sector collaboration is the shared benefit of using the task force model for emergency response. Additionally, Levine noted that the task force model has “taken hold,” so that community planners are not waiting for a disaster to work on projects for community preparedness and improvement.

Individual-Level Response

While the Task Force presented a unified front of combined expertise and capacity to combat the effects of COVID-19 in Greenbrier County, the individual level of the response process was also vital. Reaching out to offer assistance, even if it is to take one responsibility off of an individual person's plate, can make a huge difference. Volunteers helped ensure that GCHD and GCHSEMA could continue to serve the community and allowed them to efficiently delegate expertise.

Barriers

Access to Tools for Success

Levine was in a different, though similar, role during the 2016 floods. One lesson he learned during that time was that while a community may not know exactly where it will need to scale up operations in an emergency, need often arises within a few different domains — volunteer coordination, data and information management, and communication. This proved true during the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force's response to the pandemic. However, while communities often have access to the necessary people and tools to coordinate a response, Levine noted that there is rarely a single organization responsible for every aspect of a large-scale response. This points to the need for cross-sector collaboration for a successful response.

Transportation Needs

Transportation is a long-standing concern for the Greenbrier County community, and it is a barrier that underlies many challenges in rural areas, noted Levine. West Virginia is very mountainous, and people often live in isolated geographic areas. Traveling great distances is expensive, both for individuals and responders. Since Greenbrier County is so large, transportation was a significant barrier to accessing vaccines and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Broadband Internet Access

The Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force was responsible for reaching a lot of people and coordinating a complex emergency response. Broadband is critical for both emergency and non-emergency response coordination — during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, however, access was not adequate for the Task Force's response activities. Accounting for the fractured system of broadband and cell phone coverage in the area made everything “that much harder.” It does not have to be hard, noted Levine — “nearly every house in America has electricity” or access to power, so there is no reason that broadband should continue to be an impossible issue.

Since the pandemic started, Greenbrier County as well as Pocahontas County, located north and contiguous to Greenbrier, have implemented local broadband task forces. The local broadband task force in Greenbrier County is a non-emergency task force, comprised of individuals and organizations working at the “hyper-local level” to improve broadband access as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic response. According to Levine, Greenbrier County has watched a lot of money go to projects that have not effectively increased access to broadband in a significant way. Being able to collaborate with a cross-sector approach on the local level is one way in which Greenbrier County can create progress to improve infrastructure to be more resilient against the next disaster.

Lessons Learned

Stay in Practice

Following the Greenbrier County COVID-19 Task Force-led response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the rural county, Levine took away an enhanced understanding of the importance of emergency preparedness for his community. He expects the Task Force will need to activate a response, to some degree, as regularly as every 4 or 5 years. Maintaining relationships for cross-sector collaboration and practicing regular preparedness activities is an important takeaway when reflecting on both the floods in 2016 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Grasstops Response

Knowing which types of partners should collaborate and getting them to join in the planning process, systematically and regularly, is vital. The “grasstops” community stakeholders refer to leaders in the community who possess the high-level connections needed to mobilize resources and support for quick emergency response action. Community organizers cannot always know what actions will need to be taken for future events. From an emergency perspective, however, knowing who needs to be included in the conversations is powerful.

Rural-Urban Divide

The difference between individuals living in rural areas, compared to urban or suburban areas, in terms of wants and needs surrounding vaccines is not as big as it was often made out to be, Levine says. Even in areas where it appears there may be a stark difference, such as in vaccine uptake, Levine argued that it is not clear-cut. Rural areas face different barriers and challenges to getting COVID-19 vaccines than do non-rural areas. As an observer on the ground in Greenbrier County, Levine noted that nearly the entire community was appreciative of the Task Force's efforts. They saw the adjustments and systems that were created to maintain progress and were keenly aware of the COVID-19 response initiatives undertaken in the rural county.

Intentionality in Collaboration

It is important that those directly involved in an emergency response actively reach out to those not currently involved. Intentionally asking for help brings people into the fold. If there are sectors of the community not involved, the best way to include them is to offer them space to join the response. Every organization has something to offer that could strengthen and enhance response capacity. The COVID-19 pandemic and the local floods in 2016 showed the Greenbrier County community that they were capable of more than they thought, according to Levine.

Advice

Plan in Advance

Begin cross-sector collaboration before a disaster or emergency occurs. Having connections in place, making sure that conversations are happening, understanding who is willing and able, and having the right person to share resources or capacity makes the relief and response process easier once an event occurs. Map out who will serve as the central communications manager, what responders are going to be brought to the table, and how that information will be disseminated within a feedback loop to ensure the wider community has the information they need. Identify anchor organizations within the community and establish if they will be part of community response, what resources they will be willing to share, and whether they will undertake activities that are not necessarily “part of their wheelhouse.” Understanding what organizations exist that would be willing to support the community, in line with their mission statement, is integral.

Person(s) Interviewed

Julian Levine, Director of Community Engagement and Outreach

Center for Rural and Community Health, West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine

Opinions expressed are those of the interviewee(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.