The Big Horn Basin Healthcare Coalition Coordinates Emergency Response Training in Frontier and Remote Areas of Wyoming

What Happened

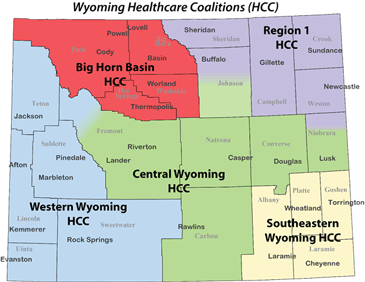

In April 2022, the Big Horn Basin Healthcare Coalition (BHB HCC) partnered with healthcare facilities, providers, and emergency management professionals to conduct a utility outage and burn patient surge training exercise in rural Wyoming. The BHB HCC and its partners maintain regular training events for first responders and volunteers so that responders feel confident facing the multiple hazards that are specific to Frontier and Remote Area (FAR) emergency response activities. The BHB HCC serves 4 rural counties within the northern part of Wyoming, including Big Horn County — which is designated as FAR level 4 — as well as Park, Hot Springs, and Washakie Counties — all of which are designated as FAR level 3. Together, these counties make up Wyoming's Region 5 healthcare coalition and cover over 14,000 square miles of land. Regular trainings are essential for responders in FAR areas that must contend with multiple different terrains, extreme weather events, limited resources, seasonal tourist influxes, and other challenges.

The BHB HCC is made up of 30 members from the area's 6 Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and is organized by Margaret Staab, the Region 5 BHB HCC Healthcare Readiness and Response Coordinator. Three of the CAHs within the region have long-term care facilities, and there are 3 ambulance services providing transportation across the region. The BHB HCC's primary goal is to provide support to CAHs within FAR areas during the emergency planning, response, and recovery processes. Because of this, the BHB HCC must incorporate an integrated partner and community emergency response framework. The framework is outlined in the March 2022 ASPR TRACIE Healthcare System Preparedness Considerations Speaker Series, in which Staab was featured.

Coalition Structure

The BHB HCC has multiple partnerships in place that aid in its mission of supporting hospital preparedness and funding. Each of the 4 County Emergency Management Coordinators, funded through the Wyoming Office of Homeland Security, participate in the BHB HCC. They are the first people contacted during an incident or emergency — the County Emergency Management Coordinators then contact the County Public Health Response Coordinators (PHRC) through the county offices of public health. One of these core members then contacts Staab at the BHB HCC, who will activate the coalition and notify officials at the state level to prepare stand-by response capacity, if needed.

Other members of the BHB HCC include partners from public health and emergency management services, such as ambulance directors, CAHs, long-term care facilities, and various clinics within the hospital district. The Chief of the Worland Fire Department, located in Washakie County, serves as a BHB HCC member and is also the chief of the Regional Emergency Response Team for Region 6 (RERT 6) of the Wyoming Office of Homeland Security, which is based in Cody, Wyoming. The 4 counties that make up the BHB HCC — Big Horn, Park, Hot Springs, and Washakie Counties — also comprise the Wyoming Office of Homeland Security's RERT Region 6. The RERT 6 are trained in hazardous chemical management and have the capacity to respond to toxic, chemical, or railway freight spills, chemical fires, hazardous materials (HAZMAT) clean-ups, and evacuations.

In addition, there are 2 search and rescue (SAR) team leaders in the BHB HCC: one is the Medical Advisor for Park County Search and Rescue, and the other is the Big Horn Search and Rescue Training Coordinator. There are 6 SAR agencies within the 4 counties that the BHB HCC serves. Hot Springs and Washakie Counties both have one SAR operation each but, due to the large size and geographic spread of the remaining Region 5 counties, Park and Big Horn Counties each have 2 SAR operations. The county sheriffs operate, manage, and fund the SAR teams and oversee the multiple trainings SAR responders must undergo. The BHB HCC supports SAR by providing training and materials such as medical backpacks during expeditions.

All of the SAR responders are volunteer, which means that they have to notify their employers when a SAR response is activated so that they can leave work to respond to the call. Some SAR expeditions can take several days. The BHB HCC hosted a critical utilities outage and patient burn surge exercise in 2022, in which SAR was activated. The sheriff, who acts as the Incident Commander under the Incident Command System (ICS), deployed SAR volunteers to divert traffic from the road so that the ambulance crews participating in the exercise could conduct transports quickly. The SAR team also helped the North Big Horn County Ambulance Service put patients in ambulances, because the local healthcare facilities were all understaffed at the time, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Coalition Planning

The BHB HCC implements continuous planning into their operating model. Along with collaborators and partners, they work to ensure CAHs within Region 5 have the resources and materials needed to maintain critical activities. CAHs send a coalition representative, such as a hospital preparedness coordinator, to attend meetings and relay the information back to the stakeholders at the facilities. This information sharing flows both ways, and CAH representatives can use these meetings to request resources or assistance from the BHB HCC directly.

Funding

The HCCs in Wyoming have all converted to 501(c)(3) organizations, per federal government requirements for state hospital preparedness funding. The hospital preparedness funding manager at the Office of Emergency Medical Services at the Wyoming Department of Health is responsible for writing, administering, and making funding decisions about federal grant spending. Federal guidelines decree how BHB HCC can spend their funds. They may, for example, purchase automated external defibrillators (AEDs) to distribute to county stakeholders. The BHB HCC has also purchased, using federal HCC funding, a new ventilator for a CAH that did not have access to this critical medical device during the COVID-19 pandemic.

BHB HCC stakeholders must submit a written request via a state grant application, which is first sent to the hospital preparedness funding manager for approval before being sent to the BHB HCC. The steering committee, consisting of the BHB HCC Board of Directors, has final say on whether the BHB HCC will invest in the proposed funding request. The BHB HCC uses a scoring rubric to evaluate grant applications. An application must receive a score of 70% or above before it is passed to the coalition to be voted on. The entirety of the BHB HCC must vote and the application must receive a majority vote — with a coalition of 30 members, at least 21 must vote affirmatively for it to pass. Once an application is approved by the BHB HCC, the requesting party can purchase the approved supplies and have their bill reimbursed by the BHB HCC.

Response Training

In April 2022, the BHB HCC and Big Horn County Emergency Management (BHCEM) hosted a full-scale utility interruption and patient burn surge exercise in Lovell, Big Horn County, Wyoming, to test response capacity and protection capabilities. The exercise scenario involved a pipeline explosion that resulted in a surge of burn patients needing advanced medical care. Responders included the SAR volunteer team, and the sheriff served as Incident Commander. During this exercise, law enforcement and the Incident Commander were able to arrive onsite quickly and begin diverting traffic with the help of SAR volunteers. It was also important that the disaster site be well-controlled and secure so that only necessary personnel had access to the scene. Triage, transportation, and patient transfer were the main roles of the participating healthcare facilities.

After-Action

Following the April 2022 burn surge exercise, the BHB HCC and BHCEM compiled an after-action report/improvement plan (AAR/IP), which functions to help participants evaluate strengths and weaknesses from the exercise and analyze core response capabilities. This report is valuable as it identifies areas for improvement, suggests corrective action, and contributes to the continuous planning process. Stakeholders at the state and local level as well as external stakeholders participated in this exercise. With so many involved, the AAR/IP can also be a useful tool to comprehensively debrief participants and identify any challenges that may be overlooked otherwise.

Success Factors

Training for Response Capacity

Staab emphasized that the more training the BHB HCC provides, the greater the response capacity of emergency responders will be during an incident. SAR volunteers undergo an abundance of tactical training, including ropes training to learn how to scale a cliffside, water training to perform boat rescues, and helicopter training to learn how to safely parachute from the craft for response in remote areas such as mountains, public lands, and Yellowstone National Park. They also receive training on patient handling, including transfer to a stretcher, loading into an ambulance, applying a cervical spine collar (neck brace), performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and administering basic first aid. In addition to skills training, the BHB HCC sponsors ICS and Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) trainings for the SAR volunteers and, as a requirement of federal grants, provides access to Public Information Officer (PIO) training for coalition members and healthcare facilities. The BHB HCC offers ICS and PIO training opportunities to the broader community as well, including businesses outside of the coalition, due to its usefulness in emergency response.

Stop the Bleed Kits

The BHB HCC funds an annual project to provide Stop the Bleed kits and training to each coalition member. Once the members are certified, they receive a certificate that allows them to train others. Stop the Bleed kits are one-time-use medical kits that can be used to clean wounds and apply tourniquets during medical emergencies. The BHB HCC provides Stop the Bleed kits to every sheriff vehicle across the Region 5 counties, and SAR team members have used them on rescue operations to save lives. In one instance, a hunter was bitten by a rattlesnake in a remote area. SAR located him and performed medical assistance at the scene, since he was unable to drive his car due to swelling from the venom. The local hospital does not have rattlesnake antivenom due to the infrequency with which it is needed, so the Stop the Bleed kit helped first responders stabilize the hunter before transporting him to a larger medical facility. The BHB HCC performs monthly outreach to public health and emergency response coordinators to ensure that the sheriffs' offices, highway patrol, SAR volunteers, local police officers, local fire departments, ambulances, and businesses are trained and equipped with these life-saving resources.

Types of Response Players

Staab referred to the different players in emergency response as crucial during FAR area incidents. Some responders would rather work ahead of an emergency and undertake tasks like handling paperwork. These individuals are involved in preparedness and planning. This is how Staab views her own role within the BHB HCC. The others are first responders who are directly involved in response activities. These players, such as ambulance crews, sheriff's offices, SAR, police departments, and fire departments, are able to jump into an emergency situation at a moment's notice. Both of these responder types are essential to successful emergency planning, response, and recovery, especially in the remote areas of Wyoming.

Response and Special Populations

The BHB HCC is prepared to respond to multiple potential incidents. Their response capacity includes a volunteer sandbag team to help distribute sandbags along the riverfronts and creeks in the event of heavy rainfall, mountain high runoffs, or flooding. The area frequently deals with hailstorms, and in a particularly bad event, a few towns within the BHB HCC's jurisdiction lost power for several days. SAR was deployed by the Sheriff to go door-to-door to check on residents and help them relocate to a community center where the American Red Cross had set up an emergency shelter with food, hot water, and generator power. During this event, the BHB HCC compiled an Access and Functional Needs (AFN) list for individuals in the community so that responders and healthcare staff would know where to focus resources for potential response. An individual with hearing loss, for example, may not hear an emergency siren, while an older adult or an individual with a disability may be at increased risk for illness or injury in a prolonged power loss event. These are considerations that emergency responders must be aware of in their community, said Staab. Populations with access and functional needs should be among the first people contacted in the event of a disaster or emergency incident. SAR had access to this list and knew which residences were occupied by homebound residents. SAR, however, does not have the authority to enter a home for a wellness check if no one answers the door. In situations such as this, it is crucial that SAR volunteers and law enforcement work together closely so that wellness checks can be performed by authorized officers as quickly as possible.

Barriers

Staff Shortages and Turnover

Traveling healthcare and laboratory staff from around the world responded to the need created by the COVID-19 pandemic in rural Wyoming. However, traveling providers do not always have rural experience, which can be a difficult adjustment. Travelers as well as permanent staff often experience fatigue and turnover due to high demand. In addition, travelers typically only stay a few months and do not have the extra time to become involved in the community.

Laboratory staff work 12-hour days while the clinics are open and remain on call when lab work is required after-hours. The nationwide shortage of laboratory technicians, said Staab, means that there cannot be specialists in the lab. There are not enough resources to have a separate person for phlebotomy and chemistry within the blood bank laboratory, for example. Staff must know how to carry out all processes, operate all equipment, draw blood, and assist in emergency situations. In fact, noted Staab, a laboratory technician at one of the BHB HCC facilities is also a volunteer SAR team member. When a call is put out for a SAR expedition, the clinic administrator must make a tough decision on whether the lab can spare the staff member to assist in the rescue. The answer, said Staab, is usually no.

Rural healthcare providers and laboratory staff must have multiple roles and skills in the small facilities. Staab recalled the multiple roles of one of the BHB HCC's members, who serves as the Coalition Clinical Advisor; as the trauma, emergency department, and ambulance service director at their healthcare facility; and as a leadership team member for each of these positions. Another hospital in the BHB HCC has only 2 full-time staff members and a traveler who must cover the hospital's needs “24/7/365,” which results in inadequate staffing for shift trade-offs. This problem was especially concerning during the COVID-19 pandemic. A hospital can have 10 open beds, but if every nursing staff member is out sick, then there might as well be no beds at all. The same is true during a pandemic if a hospital is without the necessary training, supplies, medical equipment, and personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to carry out regular activities. Complications such as these, said Staab, are the reality of small, rural facilities.

Ambulance Availability

The 2 largest ambulance services in Region 5 have only 7 ambulances each. If there is an incident involving multiple injured individuals, all the ambulances in the immediate vicinity will be called to the on-scene response. To cover the gaps, backup ambulances from other counties will need to be requested, and chances are, said Staab, that other counties will have already been called to respond to the scene. Backup ambulances will then have to cover all of the responding units, which can leave these small services understaffed in additional areas. It is a “snowball kind of effect,” according to Staab.

Incidents such as these may also require flight services, for a hard-to-reach emergency situation or for a medical transfer. The nearest Level 1 trauma center to Region 5 is located in Billings, Montana — though medical evacuations and air ambulances might be diverted to Denver, Colorado, or Salt Lake City, Utah, depending on the circumstances and weather. Only one of the CAHs within the BHB HCC region has a helicopter; however, private air ambulance services operate across multiple HCC regions.

Geographical Hazards

First responders face a unique combination of threats in the rural counties of Wyoming, including mountain, forest, and desert geography; wild animals; extreme weather events such as blizzards, floods, and wildfires; and travel barriers related to the long distances between medical facilities. Combined, Big Horn, Park, Hot Springs, and Washakie Counties span over 14,000 square miles with a population of slightly over 37,000 residents, which is fewer than 3 people for every square mile. With vast amounts of land relative to the population, it is difficult to ensure that first responders and healthcare personnel are located in close enough proximity to an incident to deliver timely response. In a mass casualty or large-scale incident, coordinating ambulance and healthcare staffing coverage is additionally difficult, as neighboring responders will be called to the scene, away from their posts, to help process and treat the large patient volume. Wilderness, avalanche, and backcountry responses may be required during extreme weather events or in SAR operations. It is important that responders and healthcare facilities have contingency plans that take into account the differences in weather during different months of the year as well as geographic or terrain-related hazards within the locale of operation.

Communication

The BHB HCC prides itself on its communication during an incident response. The planning process devotes attention to communication resources, such as purchasing radios, ensuring the SAR responders have their own radio frequency, training them on how to properly use equipment, and organizing a contact list with updated information to be distributed among coalition members. However, the geography in the rural Wyoming counties causes communication barriers. The BHB HCC typically relies on email and text messaging to quickly notify coalition members of an incident. Unfortunately, cell phone reception is not available in many places in the state, said Staab. Despite the presence of cell towers, there are still dead zones or areas with no cell phone reception. Unless people located in these remote areas have a radio, noted Staab, there is no efficient way to maintain contact in an emergency. The BHB HCC is always searching for ways to improve their communication, said Staab. Reliance on the internet and computers for outreach and access to electronic backups, for example, is not sustainable if there is a power outage. The BHB HCC, therefore, has developed contingency plans for communication maintenance during emergencies that account for a variety of events.

Misinformation

While the BHB HCC provides PIO training to coalition members free of charge, there are never enough trained PIOs to have a “unified media presence,” said Staab. This level of coordination and communication is crucial to counter misinformation during an emergency. Social media presents a challenge, noted Staab, as PIOs must be well-versed in a variety of online platforms in addition to traditional media such as radio and television. Ensuring that a unified message is maintained throughout the course of an incident remains a challenge for responders.

Lessons Learned

Backup Support

The 2022 utility outage and patient burn surge exercise involved a large number of local responders and hospital staff. All of the participating CAH's ambulances were involved in the exercise response, in addition to extra staff, to simulate an “all hands on deck” approach during an emergency. However, the CAH did not request a backup ambulance prior to the event, nor let the BHB HCC or another ambulance service know that their ambulances' regular jurisdiction would need to be covered by a partner in case of a medical emergency. It would have taken another ambulance at least 45 minutes to get to the CAH from any other facility; if someone in Lovell had a medical emergency that required transport, such as a heart attack, there would not be anyone available to get them to the hospital. As a result of identifying this oversight, improvements have been made to preparedness plans that suggest requesting 2 additional backup ambulances and backup staff prior to the exercise.

Advice

For rural and remote communities and coalitions implementing emergency response and trainings, Staab suggested involving as many people as possible in the planning, training, and response processes. Staab emphasized that the BHB HCC is not her coalition — while she is the coordinator, it belongs to the community. The more people you get involved and ask for help, the more active your coalition will be, she noted. A coalition must be built “from the bottom up, not the top down” if it is to be successful. It is important to recognize where people have knowledge and resources to share. Ultimately, she said, the members themselves are the coalition and it is “all about the people involved.”

Person(s) Interviewed

Margaret Staab, Healthcare Readiness and Response Coordinator, Region 5

Big Horn Basin Healthcare Coalition

Opinions expressed are those of the interviewee(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.