Landslide in Sitka, Alaska, Leads to Unique Approach for Creating an Early Warning System

What Happened

Sitka, Alaska, is a tight-knit community of approximately 8,700 people situated on Baranof Island in southeast Alaska. It is flanked by towering old-growth trees of the Tongass National Forest and dramatic coastal fjords. Like many Alaskans, Sitka residents are connected to the land and sea, always mindful of the dynamic between nature and community.

On August 18, 2015, a giant rain event swept over Sitka and the surrounding area, triggering a series of landslides that devastated the community. Sitka lost three beloved community members, and the landslide damaged property and infrastructure. It took days to find the missing persons. Community volunteers, led by the fire department and Alaska Department of Transportation, helped clear roads and secured damaged buildings. Volunteers set up an emergency operating command and utilized community spaces like a church to stage efforts with residents providing food and supplies to support those aiding in rescue and recovery. This event was the first landslide disaster in many years, and it was not something the community expected.

“We have a tsunami warning system, it seems obvious that we would have landslides, but people honestly didn't worry about it,” said Lisa Busch, Executive Director of the Sitka Sound Science Center. The Center, with its front yard as the North Pacific and its backyard the Tongass National Forest, is a place for scientific research and education about coastal Alaska. Busch explained that Sitka receives over 100 inches of rain a year on average, and she noted that they are experiencing larger rain events more frequently.

Busch explained, “We used to get heavy rains in October and November, but now they start coming earlier and throughout the year.” After the landslide disaster, the community was anxious. Heavy rain events left parents questioning whether or not to let their kids go to school, and residents considered staying at a friend's house for the night if their house was in a landslide risk area. Busch explained that it was nerve-wracking and anxiety-provoking for the community.

The anxiety and loss from the 2015 landslide motivated the Center to engage in a scientific exploration of the question: “What do we need to know about landslides to protect people?” The Center created the Sitka GeoTask Force to start tackling this question and figuring out a way to help their community prepare for future landslide disasters.

The city of Sitka does not have a resident geologist, so the Sitka GeoTask Force convened scientists from around the nation and received a multidisciplinary grant from the National Science Foundation's Smart and Connected Communities program with the overarching goal of creating a landslide notification system. The city already had a tsunami warning system but felt it may be confusing to also use that system for landslides; people may not know where to go or which event was the danger. Once funding was received, the Sitka GeoTask Force pared down to a smaller group known as the Sitka Landslide Team.

“We won't know when we hear the horns, do we go uphill or do we go down?” said Busch. The city leaders, emergency planners, and fire chief were hesitant to manage a warning system that used the same notification techniques as the tsunami system. They needed to devise an entirely new system. Instead of horns and warning systems managed by city leaders, the Sitka Landslide Team, with the help of community input, developed the idea of an online dashboard that tracks geological and weather conditions and estimates risk areas for landslides.

“The idea [for the system] came from the community. It was a very Alaskan response. Let us make our own choices — very individualistic. So, with a dashboard, people can go and look at it, and then they can make their own choice,” Busch explained. If the meter says medium or high risk, the Sitka residents can decide which steps to take based on their personal risk threshold.

Initial research for developing this system included determining how information passed through the community. The Sitka Landslide Team surveyed 300 Sitka residents to understand how people learn about potential threats and see if a dashboard is an effective way to disseminate emergency information. The team then analyzed the results to discover how connected the residents are and identify potential gaps in transmitting news.

“We found that there was a core group that passed on information. And then there were people who weren't connected at all. So, the question became. How do we create a landslide warning system, so everyone has access to it?” said Busch.

The Sitka Landslide Team also worked with the Sitka Tribe of Alaska and the local tribal government to learn about the cultural and geologic history of the surrounding area in relation to land movement. As recorded in oral histories, the tribal government and Tlingit tribal citizens provided context around past land movement activity, including floods and avalanches. This offered valuable insight as it illustrated that landslide hazards weren't new but a part of a pattern within the area that the Tlingit coastal people had been factoring into their lives for generations.

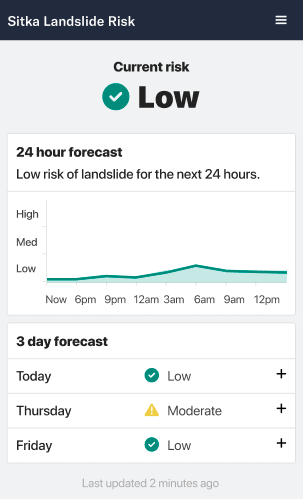

The Sitka Landslide Risk Dashboard early warning system launched in September 2022 and shares information and resources on multiple factors impacting landslide risk including a 24-hour and 3-day risk forecast, a map of current areas at-risk, and other resources to prepare for and learn about landslides.

Planning

A Community-Focused Approach

One of the strongest considerations was making sure that this was a community-centered warning system that reflected the values and needs of the community and not just a top-down scientific study. Busch described that some of the community concerns centered around home and landslide insurance and property values. Residents were worried that having a landslide system and such a large focus on being in a landslide danger zone may negatively affect insurance and property values.

The Sitka Landslide Team got a supplemental award from the National Science Foundation to explore these concerns and help dispel some myths. For example, they convened an additional workgroup of real estate experts; Alaska's Commissioner of Insurance; and Lloyd Dixon, an insurance expert from the RAND Corporation and the senior economist for the Center for Catastrophic Risk Management and Compensation. The reassurance from experts helped reduce uncertainty around how a landslide system may impact properties.

The Sitka Landslide Team held multiple workshops and listening sessions to engage the community in the process and help craft the system to their needs. Busch explained, “Sometimes the excitement of scientific study doesn't translate into actual community needs. We really wanted this project to be answering questions that the community had.” She stressed the importance of making science accessible to those impacted by results and ensuring that the language isn't jargon but something that people can easily understand to make informed decisions. “Every scientist who uses our facility is required to get science communication training from us,” Busch said.

The other small, southeast coastal Alaskan communities of Yakutat, Craig, Skagway, Organized Village of Kasaan, and Hoonah noticed what Sitka was doing and reached out for more information. The Center was awarded an additional 5-year grant to work with these communities, which are also in natural disaster zones such as landslides, tsunamis, and avalanches. Given their unique circumstances, the goal was to help the communities determine their own needs and find community-driven solutions to the hazard threats rather than copy Sitka's approach.

Response

The Role of Technology

Technology is the key part of the notification system. After the Sitka Landslide Team conducted the initial research and planning, it was down to the business of design and implementation. Grants and partnerships were crucial components in the development of the system. The Sitka Landslide Team partnered with the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), local government, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), National Weather Service (NWS), Sitka Tribe of Alaska, University of Oregon, Oregon State University, the state of Alaska, and the RAND Corporation. The team took the information from the community engagement workshops and paired it with scientific study to develop a system that was scientifically sound and reflected the community's wants and needs.

The scientific study helped identify what will inform the notification system and tools to use to measure landslide risk. The University of Oregon mapped the area. The USGS, University of Oregon, and Oregon State University deployed sensors around the area to begin testing and tracking soil moisture. Citizens agreed to maintain tipping buckets, or rain gauges, in their backyards across town and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) office at the Sitka airport monitors and provides rainfall data, which helps with forecasting. The U.S. Forest Service provided access to its historic landslide database. Social scientists surveyed community members about how they relay information to one another in order to form a picture of social network that will help inform how the landslide warning system will be distributed and used by all. A risk threshold was developed by researchers who study deep decision-making and risk management. Finally, the NWS forecasts and tracks heavy rains and tracks atmospheric rivers, the large bands of precipitation that hit coastal areas. All of these data, from tracking to forecasting, will inform the dashboard.

Another component for measuring risk is community engagement. There is what Busch called “citizen science.” For example, “if you are out on your boat and notice a landslide, take a picture and send it in,” she explained. This community effort can help identify landslides happening in less obvious areas where those who are hunting, hiking, or fishing may notice hazards that aren't captured through the strategically placed equipment.

The Sitka Landslide Team then hired a digital designer with previous experience in creating disaster dashboards to create Sitka's notification dashboard, which will be online and accessible to everyone and posted on Sitka's social media.

“Some information will be static, some will be changing. Some people want the simplicity of just low, medium, and high [risk]. Others may want more detailed data and the option to drill down,” Busch said.

The dashboard focuses on forecasting and rainfall data, but the goal is to integrate self-monitoring analysis and reporting technology, also known as SMART technology, and increase data tracking, analyzing trends over time as more data become available. However, the Sitka Landslide Team's challenge is long-term funding and dashboard management. Busch said there is a need to train local people to manage the technology and web design, figure out what to do with all the data, and analyze it for future incorporation on the site. For now, the NWS is interested in ongoing collaboration with the Sitka Landslide Team to help increase forecasting capabilities in additional phases of development for the system. And the National Science Foundation is funding another 5-year grant to do the same kind of natural hazard warning system with 6 other communities in the region.

Advice

Advice for other communities

When asked about suggestions for other rural communities to integrate hazard tracking systems, Busch recommended building community coalitions and maintaining a community-first approach. Other suggestions included starting with the broader scientific community, reaching out for funding opportunities, and identifying agencies or firms conducting similar work and may be interested in partnerships. She found that “the scientific community really does want to help [rural] communities. They want their research to help real people.” Additionally, she suggested the NWS is a good place to start since they often engage in community efforts.

“The National Science Foundation is developing a focus and increased budget to help communities. Look for available grant funding,” said Busch. She encouraged other rural communities to start thinking broadly about creative opportunities. She shared, “I just think if we can do it on an island in the North Pacific, other communities can do it too.”

Person(s) Interviewed

Lisa Busch, Executive Director

Sitka Sound Science Center

Opinions expressed are those of the interviewee(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.