Tour Bus Carrying 30 Chinese Nationals Crashes Near Bryce Canyon, Utah – Local Critical Access Hospital Helps Lead Response to Mass Casualty Incident

What Happened

On the morning of September 20, 2019, a medium-sized tour bus was traveling east on a two-lane state highway in Garfield County in southern Utah nearing its destination, Bryce Canyon National Park. The bus company, working with a Chinese travel agency, was providing an American sightseeing tour through several western states for a group of 30 tourists from China. The tourists were generally all older adults, mostly from Shanghai and its surrounding provinces. Bryce Canyon was to be the next-to-last stop on the first leg of their tour, which was scheduled to conclude later that day in Salt Lake City.

Around 11:30 a.m., the bus was approaching a slight curve in the road approximately 10 miles from the park entrance when the right-side wheels of the bus drifted onto the soft shoulder of the highway. The bus driver responded by overcorrecting, which directed the bus back onto the road and over into the wrong lane. The driver then corrected again, attempting to bring the bus back into the right lane. Next, the bus fishtailed, tipped over onto its left side, and slid nearly 85 feet before striking a guardrail on the west side of the road. The roof of the bus hit the guardrail, throwing the bus into a three-quarters roll up over the rail, where it finally came to rest back on its wheels straddling the guardrail crosswise.

The crash occurred on an empty road, and no other vehicles were involved. It was a clear day and weather was not a factor in the crash. No mechanical failure caused or contributed to the crash, and the bus driver was found to be neither impaired nor distracted at the time of the accident. The effects of the crash were severe. The roof of the bus was collapsed entirely, and 13 passengers were fully or partially ejected from the vehicle during the crash. All occupants of the bus sustained injuries, except the driver, and 4 passengers were killed in the accident.

At 11:32 a.m., the Garfield County Sheriff's Office was first alerted to the crash through the 911 system, and local first responders were dispatched to the accident site. An ambulance with the Bryce Canyon City Volunteer Fire Department (BCCVFD) was first to arrive on scene at 11:41 a.m., followed by the first Utah Highway Patrol unit at 11:48 a.m. In all, 12 local and state police, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS) agencies responded to the accident that day. Upon reaching the crash site and surveying the extent of the damage, first responders quickly designated the accident as a mass casualty incident (MCI).

The MCI declaration helped alert first responders, law enforcement, and area medical facilities to the severity of the incident and directed more resources to the scene, including additional personnel and ambulances as well as several helicopters and fixed-wing airplanes to assist with air ambulance transport. Local community partners also contributed to this effort by bringing in trailers and other equipment or supplies that were useful to the emergency response teams. The emergency response was also significantly aided by the very fortunate fact that one of the emergency medical technicians (EMTs) at the scene was a Mandarin speaker who could serve as a translator between the crash victims and emergency responders, limiting the need for assistive technology.

First aid and triage proceeded rapidly at the accident site. Within 2 hours of the crash, all injured passengers had been transported to a medical facility for treatment. Of the 30 bus passengers involved in the crash, 4 were declared dead at the scene and 7 were transported directly from the site by ambulance or air to 3 hospitals in the region (all of which were located an hour or more from the scene), while the other 19 passengers were transported by ground or air to the nearest medical facility, Garfield Memorial Hospital (GMH), which was located 17 miles from the crash site. Of the 19 passengers treated at GMH, many were subsequently transferred to another regional hospital for further care, making it a total of 5 medical facilities that received patients from the crash.

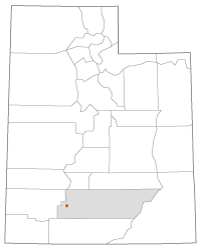

GMH is a 25-bed Critical Access Hospital (CAH) located in Panguitch, Utah. With a population of approximately 1,700, Panguitch is the largest city in rural Garfield County. As the nearest medical facility to the crash site, GMH played a prominent role in responding to the accident. The CAH is accustomed to seeing a high volume of emergency department visits due to its proximity to Bryce Canyon National Park and the number of visitors the park brings to the county annually. The facility typically sees between 3 to 9 emergency patients per day, which is above average for a hospital of its size.

Having an experienced and capable emergency department contributed greatly to GMH's success in responding to the 2019 bus crash. In fact, a few years prior, GMH received a large number of patients from a separate tour bus crash, involving a group of young people from the eastern U.S. While this previous incident was less severe and did not involve any serious injuries, it is the type of incident that the hospital was aware of and prepared for when the 2019 crash occurred. The 2019 accident, however, was of a different scale and severity than previous incidents. It was described by hospital leadership at the time as “the largest influx of seriously injured patients the hospital had ever seen.”

Just after 11:30 a.m. on the morning of the crash, Garfield Memorial's emergency department manager heard the dispatch call for EMS to respond to the accident. She immediately informed the leadership team and staff that a significant tour bus crash had occurred and patients would be arriving shortly. As the hospital initiated its incident command system (ICS) protocols and began planning its response, they were also learning more about the nature and scale of the accident.

Among the first steps taken was to call in all additional hospital staff members who were available at the time. Communicating mainly through text and word of mouth, around 80 of GMH's staff responded and arrived at the hospital as quickly as possible to perform their roles and provide help as needed. Steven Rossberg, who served as the Emergency Preparedness Coordinator on GMH's incident command team, emphasized the importance of mobilizing as many staff as possible for the response effort:

“When we did the call out to have people come in, it really was any role was needed, whether it's turning a bed or even for EVS [environmental services] or cleaning folks. And so just every department was fully engaged and needed. And if their role wasn't needed, they were needed to fill some other job somewhere. So, it was really an all-hands-on-deck type of an effort.”

Another fortunate circumstance that aided GMH's response was the fact that a team of executives from Intermountain Healthcare — the health system to which GMH belongs — was at the hospital that morning for a scheduled visit. This helped ensure that information about the crash was communicated quickly to GMH's health system partners, who were then able to coordinate and contribute resources that were needed in Panguitch. These resources included additional staff, incident command and communications support, blood products, additional tablets for interpretive services, and radiology and lab support. In addition, several members of the Intermountain team onsite that morning were trained trauma nurses who were then available to step in and help as patients began to arrive.

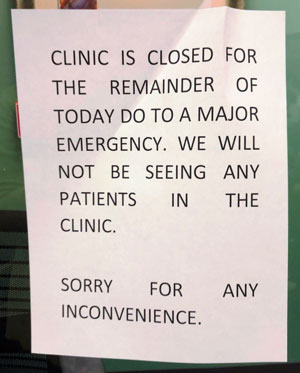

In preparation for the surge of patients, GMH began making room assignments for staff and utilizing their available space. Since the emergency department at GMH is limited to only a few rooms, GMH used other patient rooms in the hospital, rooms in their outpatient clinic, and a large physical therapy room and other spaces in the building to ensure there were enough beds to receive the incoming patients. Another preparatory step was to cancel all outpatient appointments at their Rural Health Clinic (RHC) for the day. Staff from the clinic and from the nursing home on campus were then available to aid in the emergency response.

Garfield Memorial Hospital, therefore, was well prepared when patients started arriving from the crash site. The first ambulance arrived at 12:19 p.m. with others following within minutes. One of the first and most difficult challenges they faced when patients arrived was the language barrier. Simply identifying and registering patients correctly so that treatment could be initiated and tracked appropriately was much more difficult under these circumstances. To enable communication between patients and caregivers, GMH relied on tablets to access contracted language services. They also brought in several people to serve as in-person translators. So, while the language issue was an obstacle primarily in trying to properly identify, document, and manage the patients, it did not affect the level of care they received.

Patients continued to arrive at GMH by ground and by air over the next two hours. Of the 19 patients GMH received from the crash, there were 3 with life-threatening injuries, 11 with serious non-life-threatening injuries, and 5 with minor injuries. Throughout the afternoon, hospital staff worked steadily and efficiently to provide a high level of professional emergency medical care. One resource that contributed to these efforts was the use of Intermountain's intensive care unit (ICU) telepresence capability. Through this system, physicians from Intermountain communicated with GMH healthcare providers, who helped assess the situation and provide additional resources. This became especially important in managing the air medical transport services to and from the hospital.

As the situation progressed at the hospital, a total of 11 patients in need of higher levels of care were transferred to St. George Regional Hospital, located approximately 120 miles away in St. George, Utah. Of the 8 patients remaining at GMH, 7 were treated and released that day. By 9:00 p.m. that evening, only 1 patient from the crash was still at the hospital. This patient was kept at the hospital overnight for observation before being released the following day. Overall, it was a successful response from a small, close-knit, and dedicated team of healthcare professionals at GMH. By the end of the weekend, only 12 victims of the crash remained hospitalized at any of the facilities involved, and none of the patients who received treatment after the crash lost their lives.

With an understanding of the physical and emotional trauma of going through such a terrible event, especially for victims in an unfamiliar country, thousands of miles from their homes and families, GMH's care for the well-being of their patients extended beyond the treatment of their physical symptoms within the hospital walls. The hospital social worker, nurses, and other staff at GMH made sure that patients had access to food, clean clothing, and other necessities, while arrangements were made to get them motel rooms in Panguitch after they had been discharged. Staff members helped patients find means of communication and, importantly, put them into contact with officials from the Chinese Embassy who arrived at the hospital later in the day.

The hospital also worked to identify, locate, and reunite patients with their spouses, family members, or friends who were also in the crash and hospitalized at other facilities. They arranged transportation for these patients and, in some cases, even drove them personally to facilities an hour or more away when other options were not available. Serving in multiple roles as needed is one aspect of working in a rural setting without the same resources as larger, urban facilities. Rossberg highlighted this part of GMH's response to the crash: “It's that human factor, and I think the staff at Garfield have that aspect. They're just very caring. We get a lot of thank-you notes and things like that from people we treat from all over the world. They treat them well, and that came across [in 2019] even with some people that they couldn't really speak to.”

As the work of treating the crash victims began to wind down, the hospital could turn more of its focus to other areas of its emergency response. First among these was taking care of their staff who had been working for many hours under high-stress conditions. Providing for their physical and emotional well-being became a priority. They ensured that staff had good opportunities to eat and rest. Over the course of the afternoon and evening, food services had prepared 110 box lunches to feed staff as they worked. GMH also provided resources and opportunities, both formally and informally, for staff to debrief and process the events of that day. Other areas of focus for GMH were communicating with the public and media regarding the crash and the status of the patients as well as beginning the process of evaluating their emergency preparedness based on their response to the bus crash to improve their capabilities in future emergency situations.

Success Factors

Experience, Training, and Cohesiveness

One of the main factors that contributed to the success GMH had in responding to the tour bus crash in 2019 was having well-prepared leadership and staff with years of experience working together to provide care through a broad range of emergency situations. As noted, nearby Bryce Canyon National Park attracts a large number of visitors to the area in the spring through the fall months. These visitors often engage in outdoor activities that involve some risk, such as hiking, camping, motorcycling, all-terrain vehicle (ATV) riding, boating, climbing, and horse riding, so GMH is experienced in dealing with emergencies on an almost daily basis. In addition to this, they have initiated their incident command center on several occasions in the recent past to respond to some smaller-scale situations, including a culinary water contamination incident.

Because of all this, emergency preparedness planning and training are an area of focus for GMH. Rossberg described some of these efforts:

“We do our regular exercises that we need to for qualifications, so there's usually some full-scale and tabletop-type exercises that go on… And so, from the healthcare perspective or the health department-type perspective, we had done a variety of things to work on mass casualties. It's kind of that coalition stuff, and Garfield always seemed to have things dialed in.”

Despite GMH's size and remote location, the combination of careful emergency planning, focused training, and knowledge gained from encountering a range of trauma and emergency events meant GMH staff were well-equipped to respond to a severe accident with the unique characteristics of the 2019 bus crash.

Another element that enhanced readiness was the closeness and cohesiveness of the staff at GMH. The current hospital administrator, DeAnn Brown, who served as the incident commander during the 2019 crash, pointed to the role this played in their response:

“At Garfield, we know each other well, including our capabilities. Everyone knew what their job was and just started doing it. The medical care just seemed to fall into place. Our physicians and other providers work together every day. They are friends and know each other really well, and they were just able to make things flow smoothly. The same is true of the nursing staff and other support services. Everyone just seemed to work well together.”

From an incident management standpoint then, the provision of care to the patients was one of the less complicated parts of the emergency response because of the familiarity and trust between staff members and between staff and the leadership team.

These relationships have also been developed with partners outside the hospital. For many years, GMH has worked closely with EMS, the county sheriff's office, highway patrol, and the Garfield County emergency manager, among others. Cultivating personal relationships with these partners serves to strengthen the capabilities of each organization. Brown has suggested that this is one characteristic that can be an important built-in advantage for rural providers, especially when faced with limitations and lack of resources in other areas.

Barriers

Bridging the Language Divide

The most significant barriers GMH confronted in responding to the bus accident arose from the language difference between the patients and providers. For those managing the response to the crash, this basic difference presented multiple challenges that had to be addressed in order to provide the best possible care to the patients.

This issue was front and center as patients began arriving at the hospital. In ordinary circumstances, patients are properly registered before any treatment can be initiated. This is critical because it allows the patient to be correctly identified and their treatment tracked accurately across the health system. In the case of the tour bus crash, however, the registration process was hampered due to the large influx of patients and the difficulty identifying them caused by the language barrier. Since the hospital operates under different standards during a mass casualty incident, this did not delay care for the patients. It did, however, consume considerable time and effort for the leadership team since any mistakes in identifying patients also increased the risk of medical error.

Another challenge posed by the language difference was simply gathering the resources needed to overcome this barrier and facilitate communication. GMH was well prepared for this contingency. Providers were issued tablets with an interpretive services program as a means of communication with their patients, if needed. Providers were primarily providing trauma care and working to stabilize patients to transfer them to other facilities, and translation services were not needed for this type of care. To be prepared for this situation, extra tablets had to be located and checked to see if the program had been installed and whether they were charged and ready for use. Instead of relying solely on the interpreter program, the GMH team also worked to find people who could serve as in-person translators. Along with the local EMT who was a Mandarin speaker, they contacted another community member who was available to step into this role. In addition, Becki Bronson, GMH's public information officer during the crash response, leveraged a personal connection at Southern Utah University to bring in several students from a Chinese exchange program at the school. Upon hearing about the accident, the students responded immediately, driving an hour to reach the hospital and doing what they could to help.

Bringing in these outside translators to assist in the patients' medical care, though, raised the issue of compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Since the hospital's need for translators was so urgent in order to provide necessary, life-saving care in a potentially overwhelming mass casualty incident, GMH leadership made the decision to bypass some of these requirements and allow the use of the translators. In this instance, as throughout their entire response to the accident, GMH demonstrated that the life and welfare of the patients was their highest priority.

Managing Security, Privacy, and Building Access

Another challenge for GMH with responding to the bus accident was managing the number of people coming in and out of the hospital for various reasons. In many cases, this was a consequence of the good intentions of the people involved and of life in a small rural community where everyone is familiar with one another.

First, many of the on-scene responders in the normal course of their duties ended up at the hospital after they had finished at the crash site. In this situation, the responders stayed at the hospital, looking to aid the hospital staff in whatever ways they could. Likewise, members of the community began showing up at the hospital building to learn what had happened, to volunteer, or to simply be bystanders. While much of this concern was appreciated and volunteer help was needed at certain points, the number of people at the hospital could hinder the work of hospital staff, and it also raised security and privacy issues for staff and patients.

A similar situation occurred when local media began to arrive at the hospital. In this case, the media posed even more of a privacy risk because filming or photographing on the hospital campus is not allowed under HIPAA regulations. The leadership team at GMH, therefore, had to tactfully but urgently ask people to leave the hospital premises if they did not have an active role in the response effort. They also had to ensure the media refrained from any photography of the hospital and the work being done there. In order to do this, GMH's public information officer periodically walked the perimeter of the hospital making these requests and making sure that anyone who had gathered in the area was not interfering with the ambulances and helicopters bringing patients to and from the campus or with any of the other hospital operations.

Lessons Learned

Streamlining Communications

One of the important insights that came out of GMH's experience in responding to the 2019 tour bus crash was the need to optimize their internal communications. During the response, the incident command team and hospital staff relied heavily on text messaging to communicate with each other. While the use of text message had advantages as a communication tool, they also found it had the potential to overwhelm incident command with extraneous communication. On the message thread, critical information was intermixed with less vital communication, such as thank-you messages and staff members offering each other encouragement. These messages were important for leadership and staff support, but it also made it difficult to sift out the most important information.

In response to this, GMH has updated its preparedness plan to refine the use of text messaging during an emergency response. This includes better defining text message groups and the types of communication appropriate to each group, creating distinct text groups for clinical and operational communication, as well as separate groups for external and internal communication. The goal of streamlining the use of text messages in this way is to better direct the flow of information during an emergency, make communication more efficient and responsive, and ensure that the right people get the right information when it is most needed.

Person(s) Interviewed

DeAnn Brown, Hospital Administrator

Garfield Memorial Hospital

Steven Rossberg, Emergency Preparedness Coordinator

Garfield Memorial Hospital

Becki Bronson, Public Relations/Communications Manager

Intermountain Healthcare

Opinions expressed are those of the interviewee(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.